From Egypt to Malet Place: the Wissa Wassef Tapestry in Context

By Anna E Garnett, on 13 July 2021

The Petrie Museum curatorial team is delighted to have hosted two UCL students, Naomi Allman and Max Chesnokov, as virtual curatorial volunteers during this academic year. Here, Naomi and Max describe the display project they worked on during their placement and reflect upon the experience and the skills they’ve gained during the process.

Introduction to the Project

Max and Naomi: Sayed Mahmoud’s beautiful tapestry, ‘Dahshur Lake’, was the focal point of our exhibition design project for the Petrie Museum. Woven in 2003 at the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Centre in Saqqara, Egypt, our task was to design a new display around this important object, placing it firmly in its historical and geographical context.

A key part of this project was to link the tapestry with other objects from the Petrie Museum collection that reflect the ‘image world’ of the tapestry, particularly the vividly coloured faience objects in the collection from the royal city of Amarna in Middle Egypt. The result of this project is a comprehensive display package, ready for the Petrie Museum to use at a future date when the Wissa Wassef tapestry (currently in temporary storage) is redisplayed.

The two main themes we chose for this future display are ‘Heritage in the Landscape’ and ‘Manufacturing Art’, joined together by the vibrancy of colour in a modern tapestry and in fragments of ancient faience (a glazed artificial ceramic).

The first theme, ‘Heritage in the Landscape’, presents an image of a relatively unchanged landscape from Late Dynasty 18 in pharaoh Akhenaten’s capital of Amarna (around 1350BC) to now. The beautiful floral and faunal motifs, represented in both the tapestry and in the rich faience assemblage from Amarna in the Petrie Museum, represent some of the most important elements of ancient Egyptian art. Faience is known for its vibrant colour, and it is here that we have another link between past and present.

The second theme, ‘Manufacturing Art’, takes a closer look at the production processes behind these objects. Here we explored the development of colour itself, from its mineral origins through to pigment processing and application, as well as the continuity between ancient and modern production. Most striking is the first known representation of a loom (UC9547) and an ancient limestone palette (UC2484) placed alongside a modern plastic watercolour palette and a photograph of loom types still in use today.

The object we’ve chosen as a ‘spotlight object’ for the future display is a stunning faience beaded collar from Amarna, made up of 335 beads featuring vibrant floral motifs from grapes to petals and palm-leaves (UC1957). One bead in the collar even preserves the royal cartouche of Tutankhamun! This collar presents a unique link between Amarna faience and Sayed Mahmoud’s tapestry: a chance to bring together themes of colour, motif, and aspects of the Egyptian landscape both ancient and modern.

Reflecting on our Experience

Max: Working with the Petrie Museum’s collections has been incredible. Selecting only a handful of objects from its rich and representative tapestry (pardon the pun!) was a challenging yet rewarding experience as I got to know and understand these objects on a more intimate level. I enjoyed the process of selection based on not only the comparative links that they could evoke with Sayed Mahmoud’s art but also on their actual condition and viability for display. As a conservator-in-training I have a renewed desire to care for archaeological objects such as these as best I can in my future career so that they remain in place for future generations to learn from.

Naomi: As a child, I always loved seeing how the past is in many ways extraordinarily similar to the present, while still feeling like a whole different world. As an adult, it is my dream to work in museums and heritage, perhaps undertaking a similar role as this project. Working with the Petrie Museum’s collection has been an amazing experience, and one I will never forget. This museum is so unique, and I have loved working with it. I will take from this project a renewed love in Ancient Egypt (though my heart still belongs to Classical Archaeology!) and the joys the Petrie Museum holds.

The Unsung Heroes of UCL Museums and Collections

By ucwehlc, on 6 July 2021

During 2020 and 2021 while UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog was written by Nicky Stitchman, UCL MA Museum Studies

As part of my MA in Museum Studies, I undertook a work placement with Hannah Cornish, Science Curator at UCL. My brief was to discover the different locations of UCL’s museums and teaching collections from the university’s origins in 1828. Ferreting out information from primary and secondary sources and finding maps that showed the movement of the various museums as the university expanded was fascinating, but I found myself drawn to people behind the museums. I am not talking here about the headliners – the Flinders Petries or Robert Grants of this world – but rather the curators, assistant curators and demonstrators who would have done most of the day-to-day tasks such as cataloguing, labelling, teaching, and physically moving the artefacts and objects within the collections.

James Cossar Ewart at the Grant Museum

J Cossar Ewart was the first professional, rather than professorial, curator of both the Anatomical Museum and Comparative Anatomy/Zoology Museum between 1875-1878. He was appointed after the retirement of William Sharpey (curator of the Anatomical Museum) and the death of Robert Grant (professor of comparative anatomy). In the official records, it was Professor Lankester, Grant’s successor, who refitted and rearranged the Museum of Zoology over this period but Ewart was instrumental in making the zoological preparations and was also known to have helped organise and take the subsequent practical classes that Lankester introduced to UCL.

After Ewart, there was a change in the running of the two largest museums at UCL at that time, with a separate curator appointed for the Museum of Anatomy, while the Zoological Museum (now the Grant Museum of Zoology) was titularly run by the Head of Department with a curatorial assistant.

Shattock and Stonham: Anatomy and Pathology

Mr Samuel Shattock succeeded Ewart as the Curator of the Anatomical and Pathological Museum. He had originally shown up in the records as a Mr Betty which caused me some confusion at the time, until I discovered that he had decided to change his name to prevent the extinction of the Shattock family name! Shattock never qualified as a physician but dedicated his life to pathological medicine. He was responsible, alongside Dr Marcus Beck, for a descriptive catalogue of the surgical pathology preparations at UCL. His successor Charles Stonham also worked with Marcus Beck on Part II of this catalogue and then in 1890 produced another medical pathology catalogue, which can be found online at the Wellcome Collection. In the preface to this catalogue, Dr Barlow and Dr Money acknowledge the work of Charles Stonham, and state that it is ‘to him the preparation of this work is almost entirely due’.

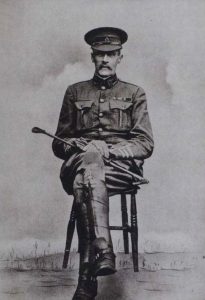

Stonham was also responsible for the division of the pathology from the anatomy collection and its rehousing within the museum. He is also remembered on the UCL Roll of Honour as not only was he an instrumental figure in the London Mounted Brigade Field Ambulance, but he volunteered as a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps during WWI and died on service in January 1916 aged 58.

Margaret Murray and the Petrie Museum

The dedication of many assistant curators at UCL is very clear. The redoubtable Margaret Murray (pictured here), who worked alongside Flinders Petrie for many years, was effectively in charge of the museum’s collections during Petrie’s many excavations in Egypt and the Levant. It should also be remembered that the Petrie Museum of Egyptology and the Department itself was founded on the collection and endowment of Mrs Amelia Edwards, who favoured UCL due to the early admission of women into the College.

Edith Goodyear and the Geology Museum

One of the first women to be involved in UCL’s museums was Edith Goodyear who was appointed as the Assistant in the Geology Museum in 1904 and subsequently remained in the department until the Second World War. Edith worked alongside Professor Edmund Garwood, reorganising the museum, teaching, and researching papers. A room in the Lewis Building was named for her, along with the First Year Student prize within Earth Sciences. It is also worth noting that in an age of inequality, the 1916/17 council minutes show Edith was paid £150, the same as her male colleague Dr J Elsden.

Keeping it in the family: Mary and Geoffrey Hett

1917 also saw the appointment of Mary L Hett as Assistant in the Zoology Dept on the same salary of £150, where she remained until she took up the post as Professor of Biology at the Hardinge Medical College, Delhi. She had followed her brother Geoffrey S Hett to UCL where he held the post of Curator of the Anatomical Museum from 1907-1910. Like his sister, he had a great interest in the natural world and was an authority on both British birds and on bats. Geoffrey became an ENT Specialist and during his time at UCL completed valuable research on the anatomy of the tonsils. Like his predecessor, Charles Stonham, he also served in World War I and used the skills learnt at UCL to treat head, and in particular, nasal injuries during this period.

The stories of the men and women who studied and worked at UCL museums over the years are many and various, and these are just a sample of those whom I have met in my research for the Mapping UCL Museums Project. We may never be able to give the Curators and Assistant Curators the recognition that their work and dedication deserve but in introducing these few to you, I hope to have redressed the balance very slightly in their favour!

Traces from the Registers: Animating the Slade’s Etching & Engraving and Lithography Prizes

By Andrea Fredericksen, on 27 May 2021

During 2020-2021, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from UCL’s History of Art with Material Studies (HAMS) on virtual work placements. These projects provide opportunities for students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

Since September 2020, Sabrina Harverson-Hill and Tianyu Zhang worked together on two virtual curatorial projects to research UCL Art Museum’s Slade Collections in preparation for the Slade 150 anniversary. Sabrina focused on the register for Etchings & Engravings and Tianyu on the register for Lithography to animate the Slade’s historic prizes in printmaking. Here Sabrina and Tianyu describe a few of the challenges and rewards of their placements:

What has been your favourite stage of the placement?

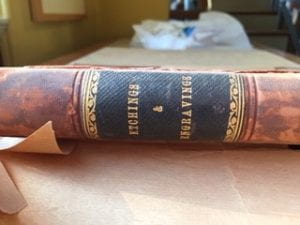

Sabrina: From day one my placement with UCL Art Museum was unusual in that it initially began remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Andrea, the Curator at UCL Art Museum, however sent all the necessary material that we needed by post. I was to be working on the register of etchings & engravings in the Slade Collections. It is unique in that it contains within it handwritten entries of students from the Slade who won prizes for etching and engraving between 1937-1981.

My favourite stage entailed researching into my list of prize-winners, particularly those who had perhaps fallen into obscurity. This for me was one of the most exciting stages but also one of the most frustrating. I reached a lot of dead ends with female artists. This seemed mostly due to potential surname changes. Subsequently, there was frequently no trace of where they went on to after their time at the Slade. Having said this, it was all the more rewarding when nuggets of information about artists were found through online research. One example was discovering that Zelma M. Blakely and her partner Keith McKenzie both studied at the Slade. Interestingly, there was more information on Blakely, her life and work, than McKenzie. The pattern with these discoveries was usually the other way around.

Tianyu: My favourite stage is looking into the lives of the artists. The process of identifying their names from the hand-written logbook and looking up the names online, looking for every possibility and narrowing it down to the one person who attended the Slade has been a very exciting stage for me, and might lead to interesting research questions. For example, to what extent is Catherine Armitage a talented woman artist under the shadow of her famous husband Paul Feiler, or about the impact of the war upon the students and their study at the Slade, as some of them seem to have paused and resumed their study in 1940s.

Digital Digging: Shedding New Light on the Petrie Museum’s Archive

By Anna E Garnett, on 20 May 2021

During 2020-2021, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, continue to provide opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

Since September 2020, Karolina Pekala and Timea Deak worked together on two virtual curatorial projects focusing on aspects of the Petrie Museum’s internationally important archive.

Karolina: Beginning a placement at the Petrie Museum was definitely out of my comfort zone. As someone with a predominantly art history background, approaching Egyptian history and objects seemed intimidating until I began to learn about the collection through the task of transcribing negative lists.

A page from the handwritten list of Petrie Museum negatives, written by volunteer Joan Merritt in the 1990s.

The Petrie Museum archive contains a detailed handwritten list describing the photographic negatives in the collection. The information on this long list, describing hundreds of individual negatives, is vital for our understanding of archaeological photography and the publication process for early excavations. This project is a good opportunity for us to contribute to the documentation, and improve the accessibility, of the Museum’s archive.

The handwritten pages contained many names of objects foreign to me, prompting many Google searches. A particular set of objects I found fascinating are the ostraca: small pieces of limestone or pottery used for writing, drawing, or sketching. I was learning something new page by page, and now that museums are slowly opening, I am excited to visit and put the objects to their names.

Despite this being a remote placement, this experience has been enriching. I was especially interested to learn about Joan Merritt, the Petrie Museum volunteer behind the handwritten pages. Knowing that the digitisation of these lists is contributing to a bigger project and legacy is incredibly rewarding.

Timea: Attempting to piece together the life of a man long gone can be a challenging endeavour at the best of times! Doing this from the writings of others only adds an extra dimension to the challenge. Yet, this was what we tried to do as we scoured trough the archives for information on Flinders Petrie.

The aim of this project was to find out more about how Petrie, and his excavations, were portrayed in the media. For this project, we drew upon our research skills to collect digital newspaper clippings which mention Flinders Petrie and produce a searchable list of these documents for future study, which will be an important addition to the Museum’s digital archive.

No great scandal was unravelled through this exercise; however, we did stumble upon articles from which we could glean aspects of Petrie’s humanity. A 1938 article in the Washington Post describes a bizarre discussion concerning the size of Petrie’s head. It seemed that the archaeologist indulged this discussion himself, perhaps even finding it humorous. Flinders Petrie revealed that, over the many decades of his life, his head had never seemed to stop growing, and seemingly struggled to find the perfect hat to fit him comfortably! Such gems reveal no great accomplishment or secret side to Petrie, but they remind us that he, too, was human.

In loving memory of Lisette Flinders Petrie

By f.taylor, on 28 April 2021

This blog was written by Stephen Quirke, Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology, UCL Institute of Archaeology. We are sharing the tribute written by Professor Quirke, who first met Lisette during his time as Curator of the Petrie Museum.

Lisette Petrie passed away on 5 April 2021 after a full life of dedication to family and friends and the world of learning.

Lisette gave her energetic support to study and learning, both in her own teaching for the Open University in astronomy, and in her practical impact in maintaining her family links to University College London, as well as to Flinders University in Adelaide. Her ties to UCL are through her grandfather, the archaeologist Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), whose Egyptian and Palestinian archaeological collections form such an important part of UCL museums and collections today.

Over many years, Lisette energetically supported us in our efforts to preserve and display the collections for a wider audience, joining us in 2007 at the opening of the SOAS Brunei Gallery exhibition A Future For The Past: Petrie’s Palestinian Collection, and in 2006 as guest of honour at the Fantasia fundraiser organised by the Friends of the Petrie Museum – where she wore the 20th century Egyptian galabiya of her grandmother Hilda Petrie, another outstanding woman of science. She also joined the Friends in their travels to Egypt, on one occasion delighting her audience with her skills as astronomer and teacher in decoding a 3,300 year old sky chart in the Valley of the Kings.

Her energy, liveliness and warmth, and her practical guidance will be sorely missed, not least in our continued quest for a safe and accessible building to house the ancient material and to welcome the widest range of visitors.

At her passing many of us relive our own vivid personal memories of her presence. We offer our deepest sympathy to Martha, Rachel and Susie, in their time of loss.

For a recent glimpse of Lisette closer to home, in her own words, and ever practical in support: https://www.hospicestrail.co.uk/completer/lisette-petrie/

Violette Lafleur: Bombs, boxes and one brave lady

By f.taylor, on 25 February 2021

To celebrate International Women’s Day 2021, we want to share with you the story of an extraordinary woman who helped save the Petrie Museum Collection during World War Two, UCL conservation student and volunteer Violette Lafleur.

Only one tin of Ptolemaic funerary masks and thirty limestone tomb-wall fragments were deemed beyond repair following the bombing raids during the Second World War. It is remarkable that more was not lost. We owe this to one incredible lady who, through sheer determination, took up the challenge of packing and sorting the collection during this tumultuous time.

Against a backdrop of wartime austerity and danger, Violette Lafleur managed almost single-handedly to save the Petrie collection.

In 1938 the most fragile and most important objects in the Petrie collection began to be boxed up and moved to Blockley, Gloucestershire, home of a naval Captain George Spencer Churchill, a cousin of Winston Churchill. The bulk of the work was undertaken by Lafleur, with the occasional assistance of College porters and a former student. The remaining 160 cases stayed on campus in the South and Refectory Vaults.

On 18 September 1940, the College sustained bomb damage that destroyed the skylights, allowing water to drip onto a tray of funerary cones and wooden toys. Despite this close shave, Lafleur returned a few days later to continue her efforts at considerable personal risk: one day a bomb dropped nearby as she laboured over the collection.

It was arduous work, compounded by the lack of packing crates due to wood shortages, meaning Lafleur had to improvise with drawers and trays. Then in April 1941, the College suffered an almost direct bomb strike and, although artefacts were not directly damaged, water from the firemen’s hoses seeped into the basement leaving cases standing in water. The artefacts had to be unpacked, dried, treated and repacked once again.

Funders were eventually secured from College coffers to finish the last tranche of repacking and some 405 cases were transferred to Compton Wynyates in Warwickshire, where part of the British Museum collection was already safely housed.

As the bombs continued to rain down it was clear London was far from safe. The Ministry of Works arranged for a further 275 cases to be moved to Drayton Court in Northamptonshire, home of Colonel Stopford Sackville. By July 1943 some 14 tonnes of cases and crates had been transported by the Pall Mall Depositing and Forwarding Company in four separate van loads, all sorted and designated by Lafleur.

Her valiant efforts were noted at the time and then-Provost, David Pye, asked that an official letter of appreciation for her efforts be written. There were plans to further acknowledge her remarkable achievements with a plaque. This never materialised, and only a short speech was given at a UCL Fellows dinner in May 1951.

Lafleur had no formal academic qualifications and her professional status at UCL was something of an anomaly. With her extensive experience of collections care and management, she was eventually bestowed the title ‘honorary museum assistant’, a role that she held until her retirement in 1953. She never received a single penny for her work, nor was it ever commemorated in the way she deserved. Her commitment, however, is not forgotten.

You can read more about some of the extraordinary stories behind the Petrie Museum on our website and in the Petrie Museum Entrance Gallery.

This article is taken from Pike, H., (2015), ‘Violette Lafleur: bombs, boxes and one brave lady’, in Stevenson, A., (ed.), The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections, London: UCL Press (DOI: 10.14324/111.9781910634042)

Cataloguing Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-Icon

By ucwehlc, on 20 January 2021

©UCL Culture/Buzz FilmsDuring Spring/Summer 2020, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog was written by Megan Christo, UCL MA Museum Studies.

Content warning: This blog contains graphic images of human remains

UCL Science Collection volunteering

For my work placement as part of the MA Museum Studies course, I was tasked with cataloguing Jeremy Bentham’s auto-icon and creating an information display to accompany the auto-icon in the student centre. Completing this work placement remotely due to lockdown presented itself with unique challenges, but was a welcome distraction from dissertation writing! Overall my work placement with UCL Science Collection was a rewarding experience, and I hope that students and researchers alike find the work I completed on Bentham as fascinating as I did.

Teaching with Collections during Covid-19

By Tannis Davidson, on 12 December 2020

Each year, UCL’s museums and collections are used in teaching practicals by university students on a wide range of courses including, but not limited to, archaeology, geography, history of art, political science and zoology. The use of collections have been at the heart of teaching at UCL since 1827 and Term 1 2020/2021 was no exception.

In the months leading up to the beginning of term in September, museum staff worked with academic partners to develop digital teaching resources for online teaching (images of objects, pre-recorded lectures and virtual tours of the museums). Reoccupation and operations groups planned how to reopen the museums as covid-secure socially distanced teaching spaces. Curators developed face-to-face teaching options with module leaders and worked with departmental administrators to organise timetables for remote students as well as those planning to be on campus.

Overall, it has been a huge collaborative effort throughout the university to support students in this extraordinary year. UCL Culture museums and collections (Grant Museum of Zoology, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, Art Museum, Pathology Museum and Science Collections) all contributed towards the UCL-wide effort to continue to provide a rewarding learning experience despite the exceptionally difficult circumstances. While there have been plenty of challenges, the response has been overwhelmingly positive and there is much to celebrate.

UCL Biosciences students in the Vertebrate Life and Evolution module during a practical in the Grant Museum. ©David Bishop

While most teaching moved online, many modules with practical learning objectives were delivered through blended teaching – a mix of online tutorials and face-to-face labs or object-based sessions. UCL Culture staff delivered 51 face-to-face teaching practicals in the museums and Object-Based Learning Lab and also developed digital content (live and pre-recorded lectures and digital images of objects) for 42 online tutorials. In total, there have been over 2700 student uses of the museum collections in Term 1 teaching modules.

UCL History of Art students in Object Based Learning Lab taught by a group of PGTAs to introduce Y1 BA students to a variety of theoretical positions to which they need to be aware of during the course of their degree. Every year they hold bespoke sessions using UCL Art Museum collections.

There are also several ongoing virtual student placements ‘based’ in the museums and a 10-month Institute of Archaeology conservation placement student working on site with UCL Culture conservators and the museum collections. Student research visits have also continued throughout the term with students accessing the collections both remotely and on campus.

UCL Institute of Archaeology conservation placement student Hadas Misgav in Petrie Museum undertaking a condition survey of metal objects in the collection.

There have been many lessons learned, adaptive responses and also innovations borne from the current situation. Smaller socially distanced group sizes in museum teaching spaces have allowed for more intimate, focussed experiences during face-to-face practicals. Likewise, smaller online group chats and tutorials have provided the opportunity for students to interact with their classmates and contribute to discussions whether they are on campus, self-isolating or in a different country. Remote students taking Biosciences Vertebrate Life and Evolution module were sent a 3D printed mystery vertebrate skull in the post so that they would have a similar specimen-based identification exercise as the London-based students.

At the cusp of a new year, new term and new challenges, we look forward to developing further opportunities to enrich our students’ learning experience and academic studies. We have been tremendously fortunate to have had the phenomenal support of the wider UCL community which has provided a safe and supportive environment and trusted us to welcome students back into the museums. Thank you!

Tannis Davidson is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL

Ask a Curator – 2020 edition

By Lisa Randisi, on 4 December 2020

On the 16th September, we took part in #AskACurator day on Twitter – we lined up four of our curators and gave you a chance to put them on the spot and ask everything you’ve ever wanted to know.

Missed it? Fear not, we’ve compiled their best answers right here.

First up was Tannis Davidson, Curator of the Grant Museum. Tannis cares for one of the oldest natural history collections in the UK including our famous glass jar of moles and 8,000 mice skeletons.

Easy one. Killer whale. I’d enjoy the lifestyle swimming with my pod in the waters off British Columbia.

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

For decades! The alcohol in the preservative will evaporate over time – it helps to have a good seal for the jar. It depends on the solution – we use 80% IMS spirit which requires topping up every 5 years or so. That said, we have specimens sealed with fluid from 100 years ago!

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

Difficult to choose! Perhaps the silky anteater because it has been in the collection since the beginning (1827) and it is possibly much older and might be the missing type specimen of this species. pic.twitter.com/ZNIcZef5Wx

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

Hi Lea! Some great advice here: https://t.co/mPJQp07YhW. It can be helpful to people in the sector (online conferences, museum social media) and get yourself out there!

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

I always liked collecting things as a child which grew into an interest in museums, archaeology, palaeontology. I worked on field projects and sought jobs in museums which led to new skills, and better jobs. It was a long and winding road!

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

What’s the oldest specimen in the museum?

The oldest specimen in the museum is the fossil worm Ottoia from the Burgess Shale in Canada (500 million years old). pic.twitter.com/X5V0JuAjc6

— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

Regarding the museum’s jar of moles:

1. People travel from far and wide to visit it

2. We don’t know why we have it (might be a research collection or was meant to be used for dissections)

3. It receives postcards from other museum animals— Grant Museum of Zoology (@GrantMuseum) September 16, 2020

(If you’re wondering, the last postcard the moles received was from the Wall Street Charging Bull.)

Next up, Curator of the Petrie Museum Dr Anna Garnett was taking questions. She looks after over 80,000 artefacts in the Petrie Museum, including the world’s oldest-known piece of clothing. Here’s what you wanted to know –

Ooh good question! For me it’s the ancient city of #Amarna – home of king Akhenaten, Queen Nefertiti (and #Tutankhamun) and a bustling population of ancient Egyptians more than 3000 years ago. I’m lucky enough to work there as well, which is a lifelong dream for me! #AskaCurator pic.twitter.com/dGuNGioQ6I

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

Yes! The ancient #Egyptians invented so many things – ancient paper, surveying equipment, medical procedures and remedies, and toothpaste! Which was apparently made from ox hooves, ashes, burnt eggshells and pumice! #AskaCurator pic.twitter.com/REmOxfhyd4

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

They were! The teeth of the ancient Egyptians often show that they were ground down, partly because of all the grit that would have ended up in their flour and bread. This would have been very painful and affected everyone in society – even the pharaoh! #AskACurator

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

I’m always so amazed when I’m surrounded by so many incredible objects! It’s never boring. We care for over 80,000 objects at the Petrie so I always spot something that fascinates me. The whole collection is also available online, for digital exploration! https://t.co/9vg6ReMpFS

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

The ‘Tarkhan Dress’ is something visitors love to see! It’s a linen tunic that was worn by a child or teenager around 5000 years ago & it’s the oldest known, most complete garment in the world. Mind-boggling! https://t.co/Si1SNAUZBt #AskaCurator pic.twitter.com/gjTd77S6lV

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

What’s your favourite Petrie Museum object? I wrote a blog about some of my favourites when I first became curator in 2017, and they still are! Especially these pottery sherds, broken and repaired in ancient #Sudan more than 4000 years ago https://t.co/9vg6ReMpFS #AskACurator pic.twitter.com/BBXuadtM8E

— Petrie Museum (@PetrieMuseEgypt) September 16, 2020

(erratum – the correct link is here)

Hannah Cornish then jumped in to talk to us about the UCL Pathology Museum, Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-icon. She also looks after our Science collections, including one of the world’s first medical x-ray images.

The first question for #AskACurator today is a corker. No, we don’t have any burps in jars, but we do have some specimens showing illnesses that might cause burping such as oesophageal reflux and stomach ulcers. https://t.co/AR5wmHwTNP

— Hannah Cornish (@HannahLCornish) September 16, 2020

(In fact, not only do we have a stomach ucler in the collection… we have 53, according to the database.)

Jeremy Bentham was a prolific writer, and if there wasn’t a word to express what he wanted to say he made one up. He gave us maximise and international, but my favourite is circumgyration, which he didn’t invent, but used to describe his daily jog around the park #AskACurator https://t.co/FPhBP9rmh2

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

Finally, Subhadra Das – writer, broadcaster, comedian and museum curator at UCL Culture – came in to talk about museums and decolonisation, race and empire.

How exciting! Part of me wants to write a whole essay to answer this, but I think the most important thing is: have a very clear idea and belief in your research, message, and what you are trying to achieve. That way, whatever the challenges, you can keep going.

— Subhadra Das (@littlegaudy) September 16, 2020

Also, find your people. I couldn’t do what I do without the solidarity of @museum_detox, and there is no greater joy as a curator than that moment where the story you are telling connects with someone who has been really needing to hear it. All power to you!

— Subhadra Das (@littlegaudy) September 16, 2020

Funny you should mention it… https://t.co/DRjNcTCmB3

— Subhadra Das (@littlegaudy) September 16, 2020

Also, I’m mindful of pretending I do all of these things at the same time, I definitely don’t. All my work is twist on storytelling and engaging with audiences, be it through teaching, exhibitions or podcasts. Most of the time I’m on the sofa drinking tea, as I am right now.

— Subhadra Das (@littlegaudy) September 16, 2020

That is so kind, thank you! I learned from the best, @GoldingTG, who worked FoH for many years @PetrieMuseEgypt. Then @steve_x encouraged me to do @BrightClubLDN and it’s been a lot of practice ever since. Have probably done 500 tours of the Galton Collection in my time!

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

In addition to diversifying the stories and themes they tell, I think being allies is really important here. Part of it is encouraging and making room for non-white professionals, and part of is acknowledging non-academic knowledge and expertise.

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

Subhadra highlighted some museum projects that are working to address the topics of decolonisation, race and empire:

Excellent question, and I’m pleased to say the answer is lots! @NHM_London are addressing this, including some brilliant work on Black History tours by @NatHistGirl https://t.co/dUMQqRY4SK

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

@HornimanMuseum are way more than an overstuffed walrus. @jcniala and @JohannaZS doing great work with the African collections there. https://t.co/8pNQl5BPPt

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

@ActivismLearn and @EconomicCurator are doing important reflective and reflexive work @LSELibrary on their institutional history of eugenics.https://t.co/U4kXDNNzT3

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

My fellow @artfund Headley Fellow @profdanhicks and @laurabroekhoven are making some pretty monumental changes @Pitt_Rivers https://t.co/eVLY5y3Ma3

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

@britishmuseum are starting to take steps to recontextualise their displays. As @DavidOlusoga says, this is an important start to address the erasure of colonised and enslaved people. https://t.co/Y8iLVXwT9m

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

There are lots of other examples, probably lots I don’t know about, so do share them here! My time for today is up, thanks for your questions and conversations and see you next year!

— UCL Culture (@UCL_Culture) September 16, 2020

That’s all for #AskACurator 2020 – until next year!

Location, Location, Location!

By Andrea Fredericksen, on 28 September 2020

During Spring/Summer 2020, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog was written by Elizabeth Indek, UCL MA Museum Studies.

As a MA Museum Studies student at the Institute of Archaeology, I had the opportunity to undertake a work placement. However, due to the very unexpected global pandemic, the placement had to be conducted remotely. This meant that I spent a majority of the placement at home in New York. It was not until the last two weeks of June that I was able to return to London and complete the job in my room in Islington instead of my room in Manhattan. My placement with UCL Art Museum was fruitful and interesting, and in this blog, I will share what I found to be the most fascinating part of my job!

Close

Close