Improving object descriptions in UCL’s Object-Based Learning Lab

By Anna E Garnett, on 28 September 2020

During Spring/Summer 2020, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog post was written by Yanning Zhao and Giulia Marinos, UCL MA Museum Studies students.

UCL’s new Object-Based Learning Lab, located in the Wilkins Building, is a purpose-built space to support and promote object-based teaching in the university. A large permanent exhibition of hundreds of objects from UCL’s collections is now on display in the OBL lab, and many of these objects were in need of updated and improved object descriptions for our museum database and online catalogue. Here, Yanning Zhao and Giulia Marinos describe their work to update some of these object records for objects from the Petrie Museum collection.

What did you do for this project?

What did you do for this project?

Yanning: We divided all the Petrie Museum objects in the OBL displays into two groups, so that we could each focus on updating half of the objects on display. The objects I researched were mainly comprised of Egyptian figurines, vessels and even fragments from statues. As most of the current descriptions for these objects are too short for readers to fully understand them, our responsibility was to review them and highlight key aspects about the objects concisely.

Giulia: In addition to revising the labels to make them more descriptive and accessible to a wider range of readers, we also researched the objects and looked for similar objects in other museum collections.

Did this project present any challenges?

Yanning: The biggest challenge for me was to describe the objects in an academic and concise style! I did not have much experience researching Egyptian artefacts, so I had to start from zero to learn how to write proper descriptions. Thankfully, Anna Garnett (Petrie Museum Curator) provided a lot of learning resources, but I still found it challenging to try to identify the features of the objects. We worked on this project remotely, so this might be because we were not able to access the objects to see them more closely in person.

Giulia: Initially, I did not expect it to be challenging to write visually descriptive labels for objects; however, I was surprised by how difficult it was to articulately and accurately describe some objects. This could be due to the complex nature of the objects, the limited views available from the online catalogue or my lack of familiarity with the objects. Although there is so much information available digitally about the objects and the Petrie Museum collection in general, there are limitations to strictly digital or online engagement. Perhaps that also shows how I miss seeing and interacting with collections in person!

Tell us some fun facts or interesting findings from the project!

Yanning: I would like to highlight this red breccia rock in the shape of a lion (UC15199, image above). Its current description does not clearly state whether it is a gaming piece or not, but by comparing it with other similar collections from other institutions, it is likely to be gaming piece for senet, a popular ancient Egyptian board game.

Giulia: I was impressed to learn how far and wide ancient Egyptian objects have been dispersed across collections around the world! In my research, I found how similar object types such as Predynastic pottery or wooden boat models can be spread over so many different institutions – from California to Italy for example (if you are interested to learn more on this, I recommend Alice Stevenson’s Scattered Finds, available as a free download from UCL Press).

Yanning Zhao and Giulia Marinos are MA Museum Studies students at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology. Their summer placement was designed and supported by Dr. Anna Garnett, Curator of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology.

Stories from the Visitor Book: Petrie Museum Visitors in the mid-Twentieth Century

By Anna E Garnett, on 28 September 2020

During Spring/Summer 2020, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog post was written by Alexandra Baker and Yanning Zhao, UCL MA Museum Studies students.

When thinking about the Petrie Museum, the first thing that might come to mind is its vast collection: from ancient Egyptian artefacts to Flinders Petrie’s own personal belongings. As visitors, we can always discover interesting facts about those objects. However, did you know that museum visitor books also tell a story about the past? They are more than simply a list of names and addresses.

During summer 2020, our team transcribed 82 pages from the Museum’s visitor book and made fascinating findings about museum visitors between 1937 and 1959.

Three fun facts about our visitors:

- We had more international visitors than you might think!

You might think the Petrie Museum attracts more UCL staff and students than people from other parts of the world, but our findings show that international scholars regularly visited the museum in the last century (the orange sections on the map indicate where visitors came from). Many historical events happened between the 1930s and 1950s, but that did not stop people from all over the world visiting the museum. These international visitors travelled to London from Spain, France, and from even further afield including Chile and Japan.

- Most international visitors were from the United States

It seems that the majority of international visitors were from the US. Most of them recorded the cities and regions they came from, including New York, Phoenix and Boston.

- English is not the only language used by visitors

We have faced some challenges to translate the language that some visitors use into English. For example, one Japanese scholar used Japanese to record the name of his university. Another visitor from Berlin, surprisingly, used hieroglyphs to record their name as ‘Neferneferuaten Nefertiti’!

Famous Egyptologists also visited the Petrie Museum:

L to R: Hilda Petrie (Petrie Museum Archive); Olga Tufnell (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olga_Tufnell);

Sidney Smith (https://www.cambridge.org)

The visitor book also shows us that big names in Egyptology visited the Petrie Museum during this time, highlighting how the collection was, and still is, an important resource for the study of Egyptian Archaeology. Our famous visitors included:

- Hilda Petrie: Egyptologist and archaeologist

- Olga Tufnell: Archaeologist who worked on the excavation of the ancient city of Lachish in the 1930s

- Sidney Smith: Assyriologist who worked at the Iraq Museum, British Museum, UCL and King’s College London

- A. F. Shore: Scholar and Brunner Professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool

Many of our visitors were students!

The Petrie Museum’s visitor book also shows us how popular the museum was amongst students from UCL and beyond. Students visited the Museum from a range of disciplines, from archaeology to physics, and interestingly art students often visited it. Working closely with students and scholars from around the world is an important part of the museum’s work that continues today.

Alexandra Baker and Yanning Zhao are MA Museum Studies students at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology. Their summer placement was designed and supported by Dr. Anna Garnett, Curator of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology.

Virtual Placement at the Grant Museum During Lockdown

By Tannis Davidson, on 28 September 2020

During Spring/Summer 2020, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog post was written by Owen Fullarton, UCL MA Museum Studies student.

I worked with the Grant Museum of Zoology in two capacities this academic year. Firstly, for the Collections Curatorship module and then for my placement both of which are part of the Museum Studies MA. My experience with the museum has been extremely enjoyable and it has been a great opportunity to work with a very interesting and unique collection. Through my placement, I also gained a significant insight into how a museum operates and the types of work curators carry out, in my case, primary transcription of archival documentation.

I was fortunate to be able to view the museum before the pandemic and carry out my placement during it, enabling a constant connection with the Grant Museum even during these challenging times. It has some very special objects that highlight what an important zoological collection it contains and this is all ingrained within the history of UCL, my particular favourites being the quagga skeleton and dodo bones. I find these specimens interesting because they are from two extinct species and provide a physical and tangible connection to animals that we can no longer see in life. The uniqueness of the Grant Museum’s collection and the museum’s temporary exhibition Displays of Power (showing the links between nature and colonialism) made it my favourite institution to explore this year at UCL. Read the rest of this entry »

How can you care for museum collections during lockdown?

By f.taylor, on 7 August 2020

This blog was written by Conservator Graeme McArthur from the UCL Culture Collections Management Team.

The closure of UCL’s campus during lockdown has provided new challenges for UCL Culture’s Collections Management team. We are responsible for taking care of the world-class collections of artworks, ancient artefacts, zoological and pathological specimens, instruments and scientific equipment held by the university. We make sure that these objects and specimens are available for use, study and exhibition by ensuring they are properly stored, handled, displayed and documented. But carrying out this important role usually requires us to be on site!

Usually we carry out regular programmes of cleaning, auditing and conservation as well as environmental monitoring and pest control. We work closely with our curatorial colleagues to agree new acquisitions and prepare objects for loan for exhibition in the UK and abroad. Our lovely team includes Collections Managers, Conservators and four Curatorial and Collections Assistants.

So how have we cared for our collections during lockdown? Well the very first thing we did was produce a risk register to highlight areas of concern when nobody is physically present in our museums and collection spaces. Here are some of the things we’ve been keeping an eye on.

Pests!

Some of UCL’s collections are an excellent food source for the larvae of insects such as beetles and moths. This is especially true of the feathers and fur that are prevalent in the Grant Museum of Zoology. It is vital to know if there has been a pest outbreak as soon as possible, by the time someone notices moths flying around there could already have been significant damage.

Image: A drawer full of feathers and other organic material in the Grant Museum, many pests would consider this to be a drawer full of food!

To this end we have sticky pest traps throughout all of our collection spaces. These will not remove a pest threat but enough will blunder onto them to give us an indication that there is a problem. Traps are placed on the edges of rooms where pests tend to run around as well as near particularly vulnerable materials. Of course to tell us anything these need to be checked regularly which became a problem once the UCL campus closed.

Image: Pest traps and the all-important grabber to position them behind furniture.

Environment

Understanding the environment in museums and object stores is vital to the long-term preservation of our collections. Extremes in light, temperature and humidity as well as rapid changes can all cause permanent damage. We have all seen what can happen to book spines if left next to a sunny window, but this can be stopped with something as simple as closing the blinds!

High humidity can promote mould growth and corrosion whereas low humidity can cause organic materials such as wood to shrink and crack. Knowledge of the materials in the collection allows us to make an informed choice on how we want to the environment to be, though it is not always possible to keep it that way.

Thankfully even though we have not been able to work on campus during this period we are lucky enough to have a system where data is sent to us remotely. We have sensors in all of our collection spaces and we can look at this data even whilst working from home. Without people in spaces and with lights off and the blinds closed the environment has been very stable. It is easier to keep objects safe when they are not seen or used for research, but then there wouldn’t be much point in having them!

Image: A day of environmental data from the Petrie Museum.

Flooding and leaks

Many of the UCL buildings are prone to the occasional leak. Most of the collections are well protected inside cases or cupboards, but even so if left for too long a leak can potentially cause damage. It is important to check the environmental data to look for an increase in humidity that could be caused by there being standing water in the room.

To reduce these risks, we have set up socially distanced fortnightly checks of all of our collections with two members of staff who can drive in to campus. This allows us to check all of the pest traps so any outbreaks can be discovered as soon as possible. Sometimes traps become so crowded that they need replacing so we can see what new pests have become stuck.

Image: Spiders caught in our pest traps

Unfortunately, the pests caught on traps tend to attract spiders who are actually very helpful in reducing pest numbers.

During our fortnightly visits we checked all the spaces, cupboards and drawers where objects are not visible to ensure there were no other problems.

Image: Revealing a beautiful papyrus from the Petrie Museum storage

Adapting our ways of working

Working from home is an unusual situation for our team as we don’t normally spend most of our time in front of a screen! We have had to refocus to other areas, however this has allowed us to work on projects that there would not normally be time for. One of these is improving the collections database that is used as the base for our online catalogue. Over many years data has been entered in an inconsistent manner with fields being used differently by individuals and throughout different collections. We have now standardised how the fields should be used and begun to ‘clean’ the old data to remove inconsistencies. Once this is complete it will be more useful for us, the researchers and general public who use the online catalogue.

The campus has been eerily quiet during the checks but we are looking forward to welcoming back UCL students, staff and the general public in the near future!

Not all Fun and Games

By f.taylor, on 23 July 2020

This blog is written by escape room designer, museum freelancer and queer historian Sacha Coward. It explores gaming (then and now) and how playing games has always been about more than just having a good time.

Under lockdown games have become a welcome escape for so many of us. Just before typing this I was in the saccharine world of Animal Crossing sending virtual presents to a friend. Before that I was immersed in the gritty realism of The Last Of Us 2, a game which despite its exaggerated zombie apocalypse setting, can sometimes feel a little too close to home! I have been involved in online quizzes and boardgame marathons with friends over Zoom for months now. During a crisis, and particularly in times of hardship, games, as ever, are here to fill the void. But they go a bit deeper…

It’s worth saying that as an escape room designer, videogame fanatic and recently a dungeons and dragons Dungeon Master, in terms of gaming-nerdom I have got pretty good credentials! But I am also part of the LGBTQ+ community, a museum and heritage worker and I am outspoken about inclusion and diversity in arts and culture. This means I have a real fascination with games and gaming; Where they come from historically and how they are used by different people today and in the past.

Before lockdown I built a giant immersive game of Snakes and Ladders for the UCL Grant Museum of Zoology, so here I want to reflect on how and why I did it. Also I want to take a chance to briefly explore games, and look at some of the surprising things they can reveal about us. I want to think about the games we play today, the way they are evolving, and how you can see the seeds of this even in prehistory.

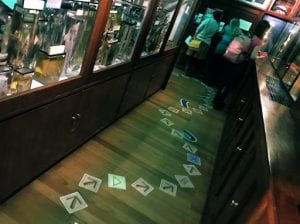

Floor vinyl created by Sheldon Goodman for ‘Snakes and Ladders’ takeover of The Grant Museum January 2020

To begin with, what is a game? It’s challenging to define exactly what a game is that includes everything that we lump under this broad category. It is more than just play (although that can be a part of it) it is a special kind of play, one that requires mutually understood rules, the presence of some kind of challenge to overcome, and an outcome or objective.

Such a description would fit equally well with Mario Kart, football, hide and seek and chess! With this definition in hand, humans have been playing games since the dawn of time. Although we don’t have physical material evidence for many games that might have been played through spoken word or action, we can still presume they were taking place. It is the ancient games with physical pieces, props and boards that we know the most about through the archeological record. The often cited oldest evidence of a game with materials associated, is the Egyptian game of Senet.

Senet dates back to at least 3100BCE. It represents the journey of a part of a person’s soul, known as their Ka, through the afterlife. it shows us something else that many games share; as well as being a fun way to pass the time, there is a central lesson or teaching goal that often applies to broader ideas of morality and society.

Even before Senet we can pretty much guarantee that games in some form or another have existed in human populations across the world since at least the dawn of modern human beings. In fact playing games is one of the defining traits that makes us human!

Today we see a myriad of games existing, played by all ages and in all areas of society. These games tell us a lot about who we are, and where we come from. A classic example is the ever fought over Monopoly; A game based on an older form known as ‘The Landlord’s Game’ created back in 1904. This game was originally designed as a teaching aid, to show and explore how economic disparity and ‘land grabbing’ was harmful and unfair. The game has since become a symbol of capitalism used by all sides of the political spectrum to explain and defend their beliefs. Most recently it was the powerful centrepiece of a speech on the impact of oppression against black people, made by Kimberley Latrice Jones during the #BlackLivesMatters protests. Games are more than games, they are some of the earliest structures we use to understand the good and bad of the world we live in.

Even one of the most seemingly simple and ubiquitous childhood games ‘snakes and ladders’ has a fascinating story that shows it too had a powerful learning objective relating to the human soul and how one should live.

Snakes and Ladders is not a Western creation, in fact its presence in the UK and Europe (and in America as the slightly neutered version ‘Chutes and Ladders’) is a direct product of empire building. ‘Moksha Pattam’ was a game which began in the Indian Subcontinent, it was part of an entire family of games arguably dating back as far as 1500BCE. These games, much like Senet, and even Monopoly, demonstrated principles relating to human life, religion and philosophy. The snakes and ladders in the game represented the conflict between Karma and Kama, I.e. destiny versus desire. Simply put, the fact that you are constrained by the random roles of a dice demonstrates the random way one might experience good and bad outcomes in life. The Victorians took this game as part of an obsession with taking, borrowing and stealing Indian aesthetics and culture. They repackaged the game with Christian values: The snakes therefore became vices, and the ladders virtues.

The fascinating colonial history of this commonplace game, and that it is a fantastic way to illustrate unfairness and bias led me to run a collaboration with the Grant Museum at UCL. On the 30th of January 2020, just before lockdown, I developed a giant immersive game of snakes and ladders as part of an evening takeover of the Museum. Working with illustrator and tour guide Sheldon Goodman and UCL museum staff I produced a giant vinyl game of snakes and ladders that had visitors walk around the cabinets as playing pieces.

We also created four different rule sets, each aligned to a different character archetype. These characters and rule sets aimed to get people to think how race, identity, sex, class and sexuality interplay in creating unfair advantages and disadvantages in real life. (This was part of the Grant Museum’s ‘Displays Of Power’ exhibition.) I felt like we were getting back to the roots of Snakes and Ladders, a tool created 3,500 years ago to teach about privilege.

Now in lockdown I am no longer building physical games, although I am creating digital escape rooms and online experiences. I am also playing a LOT of videogames; Boardgames are still alive and well but we have entered into a new world with the advent of digital gaming. Today the games we play are becoming more and more rich, complex and immersive with every iteration. Long ago this was seen as a safe space for only heterosexual cisgender male nerds, now games like every other artform are pushing for more diverse casts, and better storytelling. Mario saving Princess Peach from the castle is just not enough anymore!

Sacha runs videogame themed tours of the British Museum, where despite the lighthearted nature of the topic he covers themes of race, gender, colonisation and empire.

Even tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons and Dragons have started to realise that despite their fantastical setting, they need to mirror the lived experience of their players. Wizards of the Coast who produce the official rule sets for D&D have made a decision to remove ‘evil’ alignment from races in their series. They argue that in today’s climate talking about entire races as inherently bad or wrong is unhelpful. This is arguably in direct response to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Games, as ever, and just like their players, do not exist in a vacuum.

Sacha runs videogame themed tours of the British Museum, where despite the lighthearted nature of the topic he covers themes of race, gender, colonisation and empire.

There has definitely been pushback against these decisions by a vocal minority. The newly released Last Of Us 2 by Naughty Dog, features an incredibly diverse cast including a lesbian protagonist. This resulted in an orchestrated campaign of ‘review bombing’ before the game had even been released! Some gamers feel that gaming is becoming too ‘political’ that it should just be about ‘fun’. If anything, from my time building games, but even more from studying their history, I can see that games have always been hugely political. They have always had morals and were nearly always designed to teach us about real world principles.

All in all, games are this strange cool byproduct of human brains! We have been making them since the dawn of humanity, and there is something beautiful and cool to think that there is a thread that links me, killing zombies on a TV screen with a kick-ass lesbian protagonist, directly to an ancient Verdic game used to teach the Hindu and Jainist concept of karma! We play games to escape, and to let off steam, but games are created by and for real people with their own ideas, and feelings, and objectives. Next time you boot up your console, roll the dice, or shuffle a deck of cards, spare a moment to think what those sometimes hidden messages might be. But don’t worry, it’s just a game…

Recreating sensory experience: How haptic technology could help us experience art in new ways

By f.taylor, on 13 July 2020

Inspired by a most unusual 17th-century engraving, in this blog student Ethan Low (UCL Bachelor of Arts and Sciences) explores how haptic technology could help us understand what an artist felt at the time they created their work by recreating their sensory experiences.

For me, and I suspect many other people as well, interacting with an art piece is a process of finding peace. It is a private sanctuary, a quiet place, where you communicate with the artist on the themes of their work. A great deal of this communication is facilitated by knowing the contexts of artworks, in addition to the experiences and personalities of the artists, as told to us by curators.

But what if there is limited information about a certain artwork? Are there other means of opening up dialogues with works we know less about?

Enter Claude Mellan’s enigmatic masterpiece, The Face of Christ, also known as the Sudarium of Saint Veronica. The Face of Christ is a piece which rewards the inquisitive; viewed at a distance, it appears to no different from hundreds of other engravings from the 17th century. The imagery depicts the titular true face of Christ, which according to Christian myth, was imprinted on a sudarium, a sweat cloth for wiping the face, offered to Jesus by Saint Veronica.

The Face of Christ / Sudarium of Saint Veronica by Claude Mellan (1598-1688), UCL Art Museum

Upon closer viewing, I realized an astonishing fact; the entire image is formed by a single spiral line! Variations in line width convey the appropriate shadows in darker spaces much like the more well-known technique of cross hatching. This is complimented by the inscription below the image, which means “the unique one made by one / [like] no other”. Although some have suggested that Mellan was following in the contemporary tradition of creating representations of the sacred sudarium, (Raissis, 2014) not much else is known for certain about the work.

Detail of The Face of Christ by Claude Mellan (1598-1688), UCL Art Museum

Drawing from the concept of embodied knowledge in cognitive science, I am inclined to believe that the full depth of what Mellan felt and thought as captured in his mysterious line may be unlocked through the application of haptic technology (Low, 2020).

This was the primary subject of my Arts and Sciences Final Year Dissertation, supervised by Dr Kat Austen, the reason why I visited the UCL Art Museum early this year to meet with Dr Andrea Fredericksen, where I had my first encounter with The Face of Christ. The unique qualities and enigmatic nature of Mellan’s engraving were the primary reasons why I chose to use this artwork for the project.

Embodied knowledge refers to knowledge that is learnt and conveyed by the body, as an inseparable extension of the mind (Martínková, 2017). Neuroaesthetists Freedberg and Gallese (2007) take this further by suggesting that through embodied practices, we may be able to learn emotions felt by artists of the past.

Copying or mirroring the gestures used in the creation of artworks, they argue, could be a vehicle for us to empathize with long-dead artists. And if we think about it, this is not quite a crazy as it sounds; the motion and pattern of various marks or brushstrokes made by an artist is, after all, directly tied to their physical motion and what they were feeling when making the artwork.

Haptic technology, specifically capacitive touch sensors, was the tool I chose to allow a viewer to learn the gestures used in the creation of The Face of Christ. Haptic technology refers to any technology that can create an experience of touch by applying forces, vibrations, or motions to the user. You can find examples of haptic technology in every day life, including game controllers and joysticks.

Through an audio feedback loop, the device I designed takes in touch inputs from a viewer of the artwork and returns a religious-sounding choral soundtrack when the spiral gesture from the engraving is drawn correctly with a finger (Low, 2020). The spiral gesture was directly extracted from The Face of Christ with the help of a custom python script which made use of various image analysis libraries (Low, 2020).

Demonstration video of the artwork-viewer haptic interface (Low, 2020)

In this way, the device would teach you to trace the exact same line used by Mellan to draw the line of his masterpiece! There is still much to improve upon this very basic technology demonstrator, such as finding a way to convey pressure and associated line width, but the possibilities are certainly exciting. Like other tactile-based approaches to redesigning museum experiences, it is my hope that the technology will contribute to the ongoing effort to introduce more elements of touch and interactivity into exhibits and galleries (Howes, 2014).

Who knows, perhaps someday in the near future, we might even be able to mimic the stippling motion of Monet, or Pollock’s strong erratic strokes. The experience will probably not turn ordinary people into masters overnight, but it will bring us one step closer to seeing and, more importantly, feeling as they did.

References

Cherdieu, M., Palombi, O., Gerber, S., Troccaz, J. and Rochet-Capellan, A., 2017. Make Gestures to Learn: Reproducing Gestures Improves the Learning of Anatomical Knowledge More than Just Seeing Gestures. Frontiers in Psychology, [online] 8(1689).

Freedberg, D. and Gallese, V., 2007. Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, [online] 11(5), pp.197-203.

Howes, D., 2014. Introduction to Sensory Museology. The Senses and Society, [online] 9(3), pp.259-267.

Low, E., 2020. What Are The Possibilities Offered By Haptics In Enhancing Understanding Of Artworks? Developing A Prototype Artwork-Viewer Haptic Interface. Undergraduate. University College London.

Martínková, I., 2017. Body Ecology: Avoiding body–mind dualism. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure, [online] 40(1), pp.101-112.

Raissis, P., 2014. The Veil Of Saint Veronica, 1649 By Claude Mellan. [online] Artgallery.nsw.gov.au.

Available at: www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/340.1997/?tab=about [Accessed 4 July 2020].

Creating the best festival ever: Gaming, systems and decision making

By f.taylor, on 29 June 2020

This month we have been exploring the theme of Games & Play at UCL Culture, from solving the mystery of the ancient Egyptian game of Senet to exploring why we laugh through neuroscience.

As part of this, we spoke with David Finnigan. He is a playright, game designer and member of science-art ensemble Boho and UK interactive theatre makers Coney. For the last decade and a half, they’ve worked with government, business and research institutions to model complex systems and future scenarios.

From 2011-12, Boho were in residence at UCL to develop a new game exploring complex systems.

This is his story about the importance of games and play as a means to introduce people to new concepts, systems and ideas.

What is a system?

A system is made up of many simple parts that are connected – ants in an anthill, neurons in a brain, people in a crowd. Systems are made up of smaller sub-systems, like a muscle cell nested within a heart, and a heart within a circulatory system – and they are all interconnected and linked.

A lot of science tries to understand the world by breaking it down into small parts and looking at those parts in detail. But in the real world, everything is connected. Systems science attempts to understand the parts in relation to the whole.

We are all embedded in systems – like climate systems, social systems and political system. We need to better understand these systems in order to manage them and change them.

The way that Boho looks at systems is to break them down and turn them into games.

Games are systems

A game is a kind of system. Like any system, a game is made of simple parts that are connected – and it’s how they’re connected that is important.

Pull a lever over here and see the consequences over there. Place a token here and see the other players’ responses.

Playing a game can be a useful way to get to grips with a system, to start thinking about it works.

So we set out to create a game that would model a complex system, to give people a sense of how systems behave. We wanted to illustrate some of the interesting dynamics that pop up in complex systems, and ask, ‘how can we better manage them?’

We needed an example of a system, and the example we chose was a music festival.

Music festivals are systems

A music festival is a complex system. It is made up of smaller subsystems, such as:

• Ecological sub-systems (the land the festival takes place on, the flora and fauna, the weather and climate)

• Transport and energy sub-systems (a festival is like a temporary city, complete with all the infrastructure you find in a regular city)

• Economic sub-systems (there are formal and informal trading networks)

• Social systems (the interactions of tens of thousands of staff, artists and festival-goers).

And like many of the systems we are a part of it, festivals are prone to disasters.

So looking at a music festival is a good way to help us think through the challenges facing us in other complex systems.

The game itself

In Best Festival Ever: How To Manage A Disaster, players take on the role of festival organisers. They plan the festival from start to finish, programming the bands, building the festival site, and then dealing with the increasingly high-stakes crises that threaten to overwhelm it.

Each phase of the game looks at a separate sub-system within the festival and illustrates a different aspect of complex systems science: feedback loops, trade-offs, common pool resource challenges, tipping points, phase transitions and resilience.

Best Festival Ever started life for a season at the London Science Museum. It’s since been presented in theatres, festivals, conferences and boardrooms in cities including Singapore, Shanghai, Stockholm, Sydney and Melbourne. We present the game for general public groups, but also for schools, research institutions, businesses and government departments grappling with complex challenges.

Debrief

Playing the game is only the first step. We find that the real insights come in the debriefs and discussions that follow. That reflective space is where people make connections, draw comparisons, and start to feed the experience of the game back into their own practice.

For that reason, we often present Best Festival Ever with a scientist who works with complex systems. We play the game, and then follow it with a Q&A with the scientist where they unpack and discuss some of the concepts within the experience.

These conversations highlight the fact that everyone understands systems. We all get how feedback loops or tipping points operate – it’s familiar to us from our everyday lives. What we do in Best Festival Ever is not to teach people things they didn’t know, but to give them a shared language for things they already understand. That shared language is one of the biggest gifts that systems science has to offer.

Tactility

One crucial feature of the game is that it is entirely lo-fi, or even no-fi. There is no digital technology involved. The game illustrates complex systems dynamics using tactile objects such as wooden blocks, table tennis balls and toy trucks, designed by Gary Campbell.

During the development of Best Festival Ever, we were presenting a test show with a guest audience, reading the script off our Kindles and iPads. We realised the audience were paying great attention to the tablets in our hands, and that they assumed that all the systems in the show were being calculated in these machines. They therefore assumed that the science in the show was too complex for them to understand – that things like feedback loops were the province of computer technology.

When we got rid of the tablets and presented the show using paper and clipboards, the experience was very different. Suddenly people could see that feedback loops and tipping points can emerge from simple agents interacting through simple rules. Lo-fi – or in this case, no-fi – completely changed how people engaged with the work.

With that in mind, I’ve been drawn to representing complex systems through tactile objects wherever possible. Representing a system through a hands-on game is a powerful way to connect with people.

Make Games

If games are systems, then one of the most effective ways to learn about systems is to learn how to make games.

“If you want to learn about systems, don’t play games – make games.”

– Paolo Pedercini

To make a game based on a system, you need to map that system. You need to create a systems model which captures connections and dynamics. How are the different parts of the system connected? What is the shape of their relationship?

You need to consider the system from the perspective of various stakeholders – what do different groups need from the system, and how do they go about getting it? Then and only then can you build a working game.

One of the most satisfying parts of my job is to run game design workshops to introduce people to this practice. We start with some of the core principles of game design, and some simple exercises, then gradually work towards helping them make a quick and dirty prototype of a game based on their own system – whether a business, a community or an ecology.

Reimagining your system as a game can be a circuit-breaker to help you reflect on how it functions. It’s a useful way to thinking through where change might be needed, and what interventions are possible.

It’s also a fundamentally playful way to engage with our cultures, environments and institutions. That mindset of play and experimentation is a profoundly useful tool for us in reimagining our world for drastically changing times.

Real world play

So for people grappling with the challenge of managing complexity and engaging with systems (which is probably most of us), games such as Best Festival Ever can be a useful training device. Games can act as a kind of flight simulator for decision-making – letting us try (and fail) without consequences, before we have to make high-stakes choices in the real world.

The fictional music festival of Best Festival Ever is a place to try ideas, to debate and test strategies, to learn to work with colleagues or strangers, and to get to grips with the science of complexity. And also, if possible, to keep Chris Martin from Coldplay from getting crushed in a moshpit riot.

Download our free virtual meeting backgrounds from UCL Culture

By f.taylor, on 22 June 2020

Like many people around the world, the UCL Culture team has spent the last few months collaborating with colleagues via Microsoft Teams. Now you can bring some of our amazing collections into your meetings. Click on the images below to see them at full size and then download them to your computer. You can then upload them to the virtual meeting platform of your choice. Enjoy!

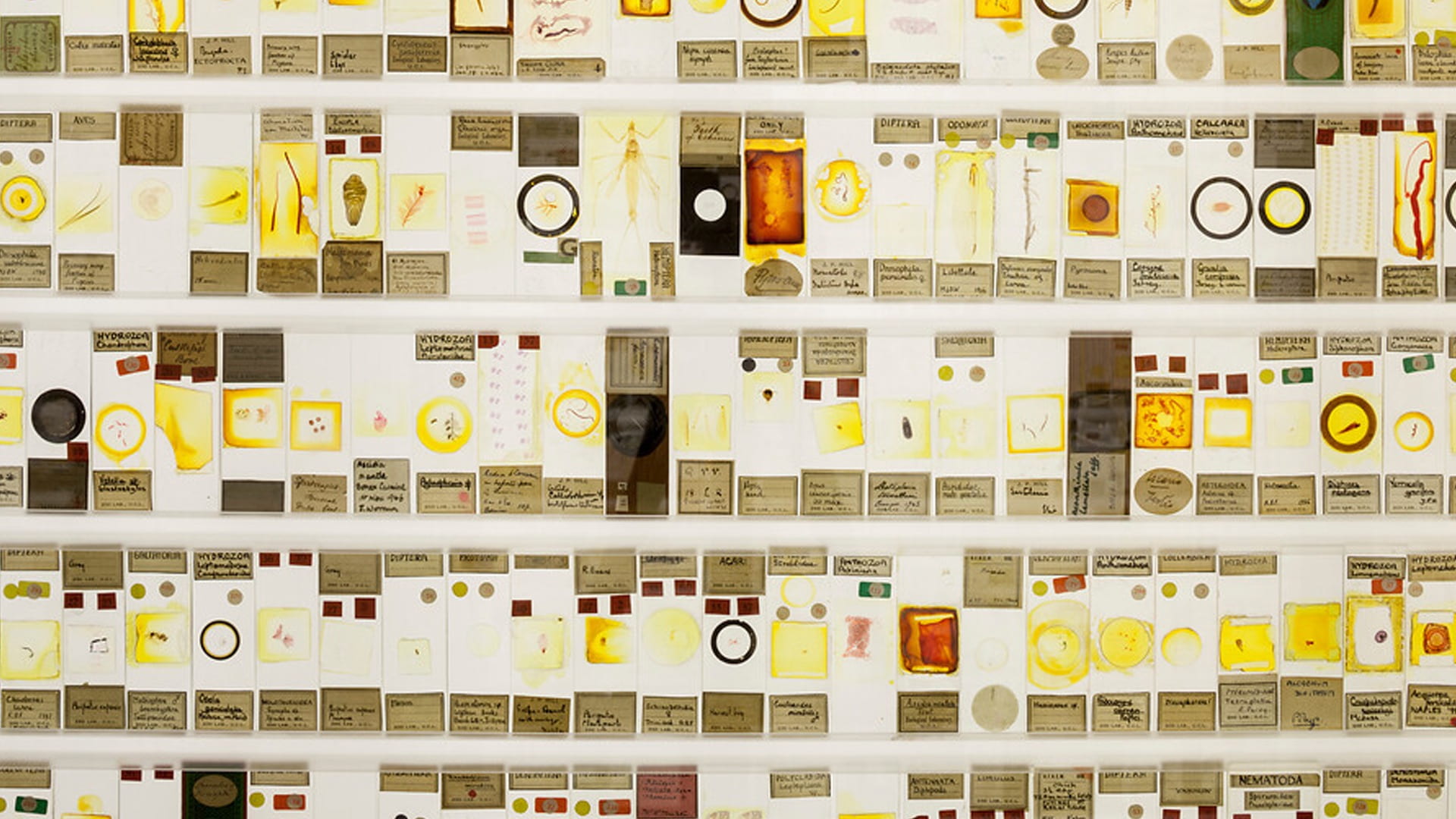

Grant Museum of Zoology

The Grant Museum of Zoology is one of the oldest natural history collections in the UK and is the last remaining university natural history museum in London. Home to 68,000 zoological specimens, the collection is a unique window on the entire animal kingdom. The final image below is from our Micrarium, a beautiful back-lit cave of 2,300 microscope slides.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

The Petrie Museum contains over 80,000 objects and ranks among some of the world’s leading collections of Egyptian and Sudanese material. Below you can see our collection of Shabtis. They are small figures in adult male or female form created to carry out tasks in the afterlife.

UCL Art Museum

UCL Art Museum holds over 9,000 paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures dating from the 1490s to the present day. One of the the most important parts of the collection is the unique archive of works by staff and students from the Slade School of Fine Art.

Bloomsbury Theatre

Bloomsbury Theatre and Studio is the home of home of cutting-edge performance in the heart of London. You can see our upcoming shows here.

William Hogarth and the Idle Prentice at Play

By f.taylor, on 19 June 2020

This post was written by Lisa Bull, MA Museum Studies, Institute of Archaeology.

Image: William Hogarth,The Idle ‘Prentice at Play in the Church Yard, during Divine Service, plate three from the series Industry and Idleness (1747)

Industry and Idlenessis one of a group of series defined as Hogarth’s “modern moral series”, for which he is arguably most famous.

The series includes A Rake’s Progress (1735), Marriage A-la Mode (1745) and The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751). He produced these works to show how depictions of modern urban life could unfold like a theatrical narrative.

This series was not commissioned; it was created by Hogarth to highlight the moral issues of society at that time that he felt were prevalent and needed attention. These prints were mass-produced due to advancing printmaking technology. Hogarth kept his designs relatively simple with the main message that weak morals led to a life of vice, crime and perhaps death.

Industry and Idlenessfollows the careers of two apprentices: Francis Goodchild, the ‘good’ apprentice and Tom Idle, the ‘bad’ apprentice. The series is 12 plates in total and it compares Idle and Goodchild in terms of their career and character development, but also their physical attributes as well.

What is Hogarth trying to say?

In Plate 3, titled The Idle ‘Prentice at Play in the Church Yard, during Divine Service,Hogarth is highlighting the issue of gambling. Tom Idle is playing hustle-cap in the street, outside a church while others are going inside for the service. He is playing with a group of questionable characters who look dishevelled and unruly. They are using a coffin as a playing table and are surrounded by gravestones and bones. They seem unaware of their surroundings, completely engaged in the game which likely involves money.

Hogarth wanted to highlight to working children the possible rewards of hard work and the risk of disaster if they did not apply themselves. He purposely kept the designs relatively simple to ensure not much explanation was needed, as his key audience was young people.

What is hustle-cap?

Hustle-cap is an old English game usually played in the streets, where coins are ‘hustled’ or shaken together in a cap before being tossed. It has been compared to the game of pitch-and-toss which is a general term that refers to games that involve chance, where bets are made in relation to the way in which coins fall (heads or tails) after being thrown.

The game involves guessing how coins (usually halfpence) will land after being thrown in a cap. The person who guesses correctly wins the money. In ‘The Idle ‘Prentice’, Tom Idle is attempting to cheat by hiding some of the half-pennies under the brim of his hat. Two of the characters on the right have seen this. It is suggested that there is betting involved as they are unaware of their surroundings and it looks tense with the expressions and stances of the characters. Additionally, there is a “beadle” (a church official) behind Idle who looks ready to strike him on the back with his cane as punishment for gambling.

How to play

The game needs two players or two teams, some coins and a cap.

- Decide the amount to include in the bet

- Players decide which side they think most of the coins will face when thrown (up or down)

- Place the coins inside a cap

- Shake the cap

- Turn the cap up onto a table

- Count the number of halfpence facing-up and down

- The player who guessed correctly wins all the coins

There may also be a version where players guess how many coins there will be e.g. facing-up and the person who guesses correctly wins the contents of the cap. This would allow more than two people to play.

Meet our Volunteers!

By Lisa Randisi, on 15 May 2020

In today’s blog, we’d like to introduce you to some people without whom a visit to our museums simply wouldn’t be the same: meet some of our wonderful team of Front of House volunteers! Here they tell all about their favourite artefacts, valuable life lessons, and what they’d do if they got to spend a night at the museum…

Please introduce yourself in a few words:

“I’m Chris, a Welsh Egypt fanatic who’s lived in France and East Africa and has dabbled in Innovation, linguistics, history and the Civil Service!”

“Hello, I’m Margaret and I did biology at UCL (which is how I start volunteering). I’m normally in the Grant as it’s my favourite of the museums and just a very cool space to be in. In my spare time, I’m normally playing the cello or reading – I love a good murder mystery! I’ve been volunteering for over three years now and each time I come in, I’ve always had a different experience.”

“Hello! J My name is Sian & hopefully you might have seen me around and about the Petrie Museum as I have been here for over 2 decades now. I’m the one who uses any opportunity to arrive in fancy dress! I’m a full-time self-employed Aromatherapist, Clinical and Holistic Massage Therapist.”

“Hi! My name is Tonia and I am a final year Undergraduate studying Archaeology and Anthropology here at UCL. I’ve been volunteering for just under two years.”

“Hello, I’m April – and before you ask, I was not born in April, it was actually October. I am also 31 and I live in Hertfordshire. I have loved Ancient Egypt since I was quite small: I remember my Granny showing me a travel book written by a painter called R. Talbot Kelly. Apparently he was also her great uncle! The book fascinated me and unfortunately for my parents, I wanted to learn more about the country he went to and painted and that’s where it all began. Since then I have accumulated quite the collection of books and other Egyptian stuff, I have also managed to get myself a degree in Egyptology with the future hope of maybe getting a Masters and PhD. I also have an obsession with dragons, books, video games and Heavy Metal music.”

Why did you decide to volunteer?

“I’ve always been fascinated by Egyptology and love museums. The Petrie has an amazing collection and I wanted to learn more about it. I also wanted to do something that involved working with the public (you never know who’s going to walk through the door next!)” – Chris

“I wanted to volunteer because of a class practical I had in the Grant during my first year. I realised it was such a great place with some very awesome specimens so I wanted an opportunity to come back and spend more time in here.” – Margaret

“My Degree was in Archaeology and History, and Masters degree was in Archaeological Research so when I was a working archaeologist after leaving University I decided to volunteer at the British Museum. About 6 months later I attended an Egyptian Mummy Study Day at the Bloomsbury Summer School (with Professor Joann Fletcher) & they suggested we visit the Petrie Museum in our lunch hour – just trying to find the Museum was an adventure. Back then you had to go through the Science Library and the back door was the front – it was like stepping into a hidden world…” – Sian

“Museums have been a source of fascination for me since I was a child and are what inspired me to study the degree I do. When I saw the opportunity to volunteer with UCL Culture I jumped at the chance! It also gives me a welcome break from university work as well…” – Tonia

Favourite object or specimen?

“My favourite specimen is the humble yet mighty hedgehog! It looks very prickly but has such a soft belly which is something most people don’t think of when they look at it. So it’s nice to have been able to see and touch the secret underside of this adorable animal.” – Margaret

“My favourite specimen is the humble yet mighty hedgehog! It looks very prickly but has such a soft belly which is something most people don’t think of when they look at it. So it’s nice to have been able to see and touch the secret underside of this adorable animal.” – Margaret

“A steatite seal-amulet depicting the form of a cat carrying a kitten. Aesthetically, I love the detail on such a small object. On a more intellectual basis, the concept of magical or ritual protection against unseen forces has long been a source of interest – especially for the anthropologist in me.” – Tonia

“The board games in the Petrie. I love the way things brings out the “fun” side of day-to-day life in Ancient Egypt. They help bring a civilisation to life, to connect as human beings with people who lived back at that time and remember history isn’t all just about king-lists and dates.” – Chris

“Anyone who has spoken to me knows – the Socks! 🙂 Again as an archaeologist I get way more excited about the preservation of materials that we don’t normally see far more than gold and treasure (which survive well). So first, I simply love that wool has survived. Secondly, I had absolutely no idea that Ancient Egyptians knitted or wore woollen socks; it was really surprising, although in retrospect desert temperatures do drop very low at night.” – Sian

“Anyone who has spoken to me knows – the Socks! 🙂 Again as an archaeologist I get way more excited about the preservation of materials that we don’t normally see far more than gold and treasure (which survive well). So first, I simply love that wool has survived. Secondly, I had absolutely no idea that Ancient Egyptians knitted or wore woollen socks; it was really surprising, although in retrospect desert temperatures do drop very low at night.” – Sian

“Say what, just one? Let me think. I really enjoy looking at the Hieroglyphs, the way they are carved or written so much better than my feeble attempts at drawing them. But I think my favourite object is the Will of Antef Meri, in the Main Gallery on the left of the big table. It is written in the dreaded Hieratic script but what I love about it is that it gives us a glimpse into someone’s life and what he was planning to do with his estate when he died. To actually have a nearly intact will, similar to one that would be drawn up today, is quite surprising. I wonder how many more there are out there.” – April

If you were locked inside the Petrie or Grant museum overnight, what would you do?

“Do my happy dance all around the Petrie museum and finally be able to look at and read every single thing! I have always dreamed of a sleepover to be honest, but I don’t think I’d sleep all night – it’s way too exciting!” – Sian

“I’d devise a new trail / treasure hunt through the collection to entertain myself and future visitors. I’d probably also play a lot of the board games in the Petrie!” – Chris

“If I were stuck in the Grant, I would explore the gallery upstairs first as there’s some very cool specimens up there that we don’t normally get to see. Secondly, I would also go around the museum sketching/photographing as many specimens as I could to compile into my very own personal museum catalogue. “ – Margaret

“I would study up on as many of the objects as possible – it would be nice to have the time to do so!” – Tonia

“Wait – do I get snacks? Because I might have to break out and buy snacks, I’m terrible for buying snacks. And don’t worry, I wouldn’t eat in the galleries! With my parents and I having to stay in all the time at the moment, the noise and constant talking can get a bit irritating, so having an overnight stay in the museum wold be wonderful. Have some snacks, a screen somewhere to watch some Ancient Egypt documentaries and slouch in a sleeping bag or blankets and pillows. It would be a wonderfully quiet night, nothing too exciting.” – April

What do you like most about volunteering in museums?

“The people! Such a variety of personalities with different interests come through museum doors that I genuinely learn something new every day.” – Tonia

“I love working with people, but as an ex-archaeologist I have to say it’s the privilege of working with all those artefacts and seeing behind-the-scenes. I’m as happy as a pig in muck just being in the Museum to be honest!” – Sian

“I think, strangely enough since I am not usually a people person, it is meeting all different kinds of people and having the chance to chat to them around a topic I know about. You get to meet people from all over the world and you get to see a small glimpse into their lives.” – April

“The best part is seeing how enthusiastic visitors are when they come in. In particular, the enthusiasm of some of our younger visitors is very contagious and such a joy to see.

It’s also really great to hear the feedback from people as they leave – they always leave full of awe and wonder which is fantastic to see.” – Margaret

What’s a valuable life lesson that museums have taught you?

“Learning isn’t just about locking yourself away in a study. It’s about getting out and interacting with people who share your sense of curiosity.” – Chris

“Not to assume anything and that people in ancient times usually have a lot more in common with us than we realise.” – Sian

“The museums have shown me that every single person has something they don’t know but can learn about. This shouldn’t be seen as a flaw necessarily but it makes all of us a little bit more human. It means that there’s always opportunities for us to be inquisitive about the world around us and improve our knowledge of it.” – Margaret

“No society or individual has any more or less value than another.” – Tonia

Bonus question: What are you going to spend time doing while on lockdown?

“I’m spending a lot of time reading about Ancient Egypt and about Twin Peaks (I’m afraid I also love that classic early 90s David Lynch melodrama and would recommend as escapism to anyone to help get through this crisis!). I’m also using the opportunity to get back into learning Chinese (along with hieroglyphics I always seem to pick the “easiest” languages!) and into international cuisine (with varying degrees of success).” – Chris

“I am currently unable to work as all my work is people-facing and hands-on. Also most of my clients are in the vulnerable category. I am currently doing what I usually do but for longer – so 3 hours meditation, practise and study instead of 1.5 hours; Tibetan energy healing practice and study; walking 2-6 miles a day; PE with Joe Wicks; gardening; blogging for my business website; advising and providing support for my clients; cooking and reading.” – Sian

“I’m lucky I’m a bit of a homebody anyway, although I am missing my friends and volunteering at the Petrie. Mostly I will be reading my many, many, many books; I’m so behind it’s hilarious. I also plan on continuing with my revision of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. I learned tham at university and it has been a while since I’ve translated anything, so I’m re-reading J.P. Allen’s book. I’m also keeping alive my newly sprouted bonsai tree – and coming from a person who killed off a cactus, that is quite an achievement so far.” – April

“I have a mountain of books I have never read and a slightly smaller one of films I have never seen, hopefully I can start to make a dent 😉” – Tonia

“I have two very difficult jigsaws that I want to attempt. I’m currently still at the beginning of the first one so I think the two of them will keep me quite busy for the next month or so. I’m also thinking of tidying up the garden a bit but that might be just some wishful thinking on my part…” – Margaret

Close

Close