Traces from the Registers: Animating the Slade’s Etching & Engraving and Lithography Prizes

By Andrea Fredericksen, on 27 May 2021

During 2020-2021, when UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from UCL’s History of Art with Material Studies (HAMS) on virtual work placements. These projects provide opportunities for students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

Since September 2020, Sabrina Harverson-Hill and Tianyu Zhang worked together on two virtual curatorial projects to research UCL Art Museum’s Slade Collections in preparation for the Slade 150 anniversary. Sabrina focused on the register for Etchings & Engravings and Tianyu on the register for Lithography to animate the Slade’s historic prizes in printmaking. Here Sabrina and Tianyu describe a few of the challenges and rewards of their placements:

What has been your favourite stage of the placement?

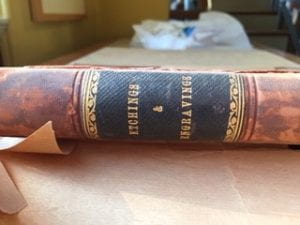

Sabrina: From day one my placement with UCL Art Museum was unusual in that it initially began remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Andrea, the Curator at UCL Art Museum, however sent all the necessary material that we needed by post. I was to be working on the register of etchings & engravings in the Slade Collections. It is unique in that it contains within it handwritten entries of students from the Slade who won prizes for etching and engraving between 1937-1981.

My favourite stage entailed researching into my list of prize-winners, particularly those who had perhaps fallen into obscurity. This for me was one of the most exciting stages but also one of the most frustrating. I reached a lot of dead ends with female artists. This seemed mostly due to potential surname changes. Subsequently, there was frequently no trace of where they went on to after their time at the Slade. Having said this, it was all the more rewarding when nuggets of information about artists were found through online research. One example was discovering that Zelma M. Blakely and her partner Keith McKenzie both studied at the Slade. Interestingly, there was more information on Blakely, her life and work, than McKenzie. The pattern with these discoveries was usually the other way around.

Tianyu: My favourite stage is looking into the lives of the artists. The process of identifying their names from the hand-written logbook and looking up the names online, looking for every possibility and narrowing it down to the one person who attended the Slade has been a very exciting stage for me, and might lead to interesting research questions. For example, to what extent is Catherine Armitage a talented woman artist under the shadow of her famous husband Paul Feiler, or about the impact of the war upon the students and their study at the Slade, as some of them seem to have paused and resumed their study in 1940s.

Close

Close