Housing, displacement and the elderly: intersectional spatial narratives from Tareek el Jdeede, Beirut

By Camillo Boano, on 26 June 2019

By Monica Basbous, Nadine Bekdache and Camillo Boano

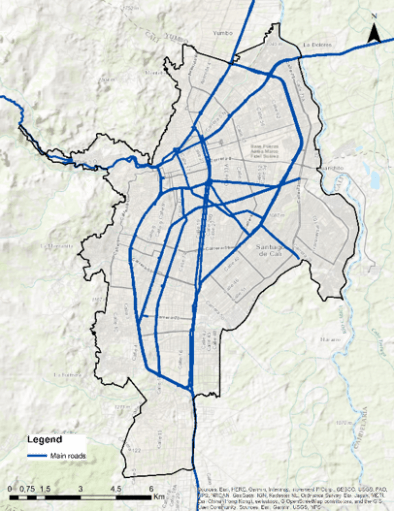

The current habitability crisis, the failure of progressive policies to consider the way cities adapt to different forms of displacement and resisting the three interrelated venomous practice of expulsions, extraction and externalisation are clear to everyone engaging with urban spatial practices. Displacement is a key characteristic of the urban present that requires interrogations across different geographies and with different methodological approaches. This short contribution stems from a current research partnership between Public Works Studio and DPU in the remit of the RELIEF Centre Project to study the effects of real estate policy and the financialisation of housing markets, which have resulted in the eviction and displacement of the most vulnerable social groups in Beirut turning the capital city into an exclusive, unjust and vulnerable place. The brief reflections below stem from the first part of the study, focusing on the eviction of the elderly in the neighbourhood of Tareek el Jdeede in Beirut, and were presented last week in London by Nadine Bekdache, Monica Basbous, Abir Saksouk and Camillo Boano in the symposium “Vulnerability, Infrastructure, and Displacement: The role of Public Services, in Lebanese spaces of Migration”.

Methodologically, the research develops housing narratives and spatial stories that, situated within a larger research, are narrated as the crossing point between the impact of market-driven urban development on housing rights in the context of Lebanon, and the strategies, opportunities, expectations and disappointments of elderly women in mitigating evictions, displacement and the social security of their families. Housing stories and diagrams were investigated with design research and drawings that were published on The Housing Monitor an interactive online platform for consolidating research, building advocacy and proposing alternatives to advance the right to housing in Lebanon.

Dwelling in Tareek el Jdeede

In this phase of the study, we examine the eviction of the elderly in the neighbourhood of Tareek Jdeede and in the wider city. Although today’s urban transformations in Tareek Jdeede may seem similar across most of Beirut’s neighbourhoods, the urban history and socio-spatial make-up of each neighbourhood determines a particular set of interactions, strategies of resilience, housing typologies and vulnerabilities.

Mazraa – the larger administrative zone containing the neighbourhood of Tareek Jdeede – gathers around 30% of Beirut’s tenants living under the old rent law. These tenants – whose contracts were established prior to 1992 – have been subject to case-by-case eviction through a candid reconfiguration after the civil war that aligned the interests of local bureaucrats with real estate development[1]. Yet with the new 2014-rent law, evictions became a city-wide condition. Many of Tareek Jdeede’s old-rent tenants, today aged 45 and above, have been evicted or threatened with eviction at an increasing rate (Public Works Studio, 2015-2017). Among these, the elderly (and the retired) carry as a social group a set of particularities that places them at odds with state housing policies, which are basically reduced to homeownership loans. They also face the threat of displacement in the absence of social housing programs and with limited social-security benefits. The elderly in some neighbourhoods are nonetheless protected by family connections and attract charity organisations that are often affiliated to sectarian institutions. When it all fails, displacement has severe impacts on the elderly’s ways of life and on their physical and mental health well-being. While their relocation generates a number of possible scenarios, we focus on two cases: on the one hand, a case of eviction and relocation within the neighbourhood; and on the other, a case of eviction and relocation to a distant suburb. Through these case studies, we set out to investigate two main questions: in what ways do urban processes and property frameworks impact the displacement – and more generally the housing conditions – of vulnerable social groups? And what urban and architectural forms are being generated as a result of housing-related displacement?

Em Yumna and Em Hassan graphic stories

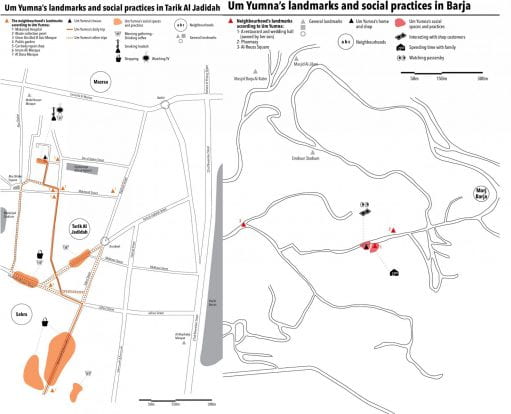

Em Yumna and Em Hassan lived a few meters away from one another, yet they had never met. While Em Yumna’s eviction led to her displacement outside of the city, Em Hassan managed to relocate across the street from her previous dwelling.

Em Yumna was 14 years old when she moved from Beqaa to live in Beirut. She had married a young Berjaoui man who worked at a company in the city, and they settled in one of the small homes of Ras Al Nabaa in the mid-fifties. A year or two later, the country would be shaken by a series of earthquakes. Entire villages collapsed in Chouf Al Aala and Iklim, and Em Yumna’s house in Ras Al Nabaa came apart. In 1957, the young family packed up their belongings and moved. At the time, Em Yumna did not intend to spend the next 55 years of her life in that little three-room house atop Zreik Hill in Tareek el Jdeede.

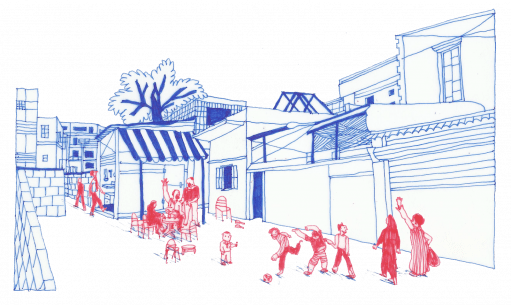

Em Yumna was evicted in 2012 when the owner made a development agreement with an investor to demolish the 3-storey building, and moved to Barja, a town located 35 kilometres south of Beirut. Her social relations and daily activities were severely ruptured, as they revolved around practices in the alley behind her house.

In 1982, Em Hassan, aged 18, moved from the neighbourhood of Noueiri to Tareek el Jdeede with her two children. Originally from the south of Lebanon, she married a relative of hers who resided in Beirut. Today, Em Hassan is in her late fifties, and continues to live in the same quarter of Tareek el Jdeede, but in a different house, after she was evicted from her previous home in 2016. A real estate company bought the building in 2011, and Em Hassan agreed to evict, using the compensation money – in addition to other resources including a loan from a religious institution – to buy the adjacent house. By doing so, she bought into a shared property, which is by itself another form of vulnerability.

Between her two dwellings lies a small courtyard that holds the past, present and future of Em Hassan’s housing. One can find her there every afternoon, having coffee and a cigarette, while at her right lies the window of the house she lived in for 34 years but is no longer hers, and facing her, the door of the house that allowed her to remain in the city. After having lived as an old-rent tenant for decades, Em Hassan’s eviction led her to buy her new home as her only means of resisting displacement.

The similarities and differences of these two cases allow us to draw a comparative analysis, looking at the impact of both the process and destination of displacement on evicted elderly and their wellbeing, by looking into the following questions: what means do the elderly have to resist displacement and what role do socio-spatial networks play in this dynamic, especially in the case of Tareek Jdeede? Does relocation within the same neighbourhood mitigate the negative impacts of eviction on the elderly and how? How do eviction, displacement, and spatial typologies impact the socio-spatial practices of the elderly, their mobility and their relation to the neighbourhood?

Reflections from the comparative analysis

Despite accessing housing for most of their lives through rent, the perception associated with property ownership as the primary means of achieving socio-economic and housing security, prompted both women to seek homeownership after eviction through mobilising a complex web of resources. The capital required to attain homeownership is tightly enmeshed with the relocation options available for these elderly women, and provisions for their children were deciding factors in this decision-making.

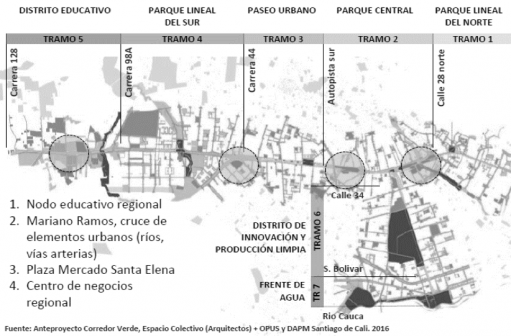

Nonetheless, the sense of security that homeownership might bring is accompanied by multiple forms of precarity and vulnerabilities. There are no affordable options to buy in the city where new unaffordable high-rise buildings are replacing the older fabric. As such homeownership for the aspiring middle class has mainly meant displacement from their city to nearby suburbs in the making, usually chosen in conformity to sectarian affiliations or origins. In contrast, the working class access substandard housing in the city, usually in the urban fabric built before 1992 that is threatened with sudden changes emanating from real estate investment or planning implementations. In the meantime, the gap between housing conditions is widening in the city. This takes a heavier toll when the same evicted units are used to exploit politically and economically vulnerable groups, particularly refugees and their families, whereby developers grant them temporary housing in order to generate profit while retaining the power to evict them spontaneously to proceed with building demolition.

Other forms of vulnerabilities linked to the production of housing in Lebanon manifest in the making of the suburbs. Apart from the poor urban planning practices resulting in environmental and spatial injustices in urbanising suburbs, the arrival of the displaced to these towns sheds light on the psychological violence exerted. The elderly endure the crumbling of social networks and support systems, the difficulty in fostering new ones, the reduction of mobility and autonomy, the deterioration of health, the loss of spatial references, and consequently the loss of sense of place and belonging. Concurrently, it was intriguing to observe how the urban morphology – spatial typology or density- can impact the building of social ties. Em Yumna was unable to adapt to her new surroundings in the suburbanizing town of Barja. Sparse urbanization and lack of accessible mobilities have led to feelings of alienation, which pushed her to seek a different spatiality for socialization: the grocery-store by the side of the road. This is echoed by Em Hassan’s husband who also opened a shop in the city, primarily as a means to socialize after the neighborhood was progressively emptied of its older inhabitants.

Through this study, we situate urban evictions beyond the confines of the city, shedding light on an emerging territorial dynamic between inner-city neighbourhoods undergoing waves of eviction and radical spatial changes, and the suburbanising towns that are hosting displaced households. Along this process, the myth of homeownership as a secure form of housing is revisited in its relation to poor urban planning practices and precarious ownership frameworks. These cases both present narratives that portray housing in the city as an access point to vital economic resources, in a context where urban space is commodified and financialised, both in practice and in discourse. They also highlight the importance of socio-spatial networks for the elderly – and the urban and suburban processes that threaten them – whereby the understanding of home takes on a larger, more social dimension than that of the physical domestic space.

Looking further into the vulnerabilities associated with homeownership, we will next investigate how the legal framework for inheritance in Lebanon perpetuates women as minority-shareholders in collectively inherited properties. Our previous research has shown that these women are often the only shareholder still living in the inherited property but have limited negotiating power and constrained agency over their housing conditions and their susceptibility to displacement.

Through an in-depth study of such a case, the next phase of our research will aim to identify the social and legal conditions that systemically place female heirs in a position of weakness regarding the future of their dwelling.

_______________________

[1]“Evicting Sovereignty: Lebanon’s Housing Tenants From Citizens to Obstacles”, Nadine Bekdache – Arab Studies Journal (Vol. XXIII No. 1), Fall 2015 – p.p. 320-350

_______________________

Monica Basbous is an architect, designer and urban researcher. Producing maps, images and writings, her work tackles questions of urban mobility, informal spatial practices, politics and representations of space, and speculative geography. Monica teaches architectural design at the Lebanese American University since 2017, and is a researcher and partner in Public Works Studio since 2016. She holds a MSc. in Architecture from the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne.

Nadine Bekdache is a practicing designer and urbanist and co-founder of Public Works Studio. She researches socio-spatial phenomena through multidisciplinary methods; including mapping, imagery and film as both processes of investigation and representation. As part of her research on urban displacement, she authored “Evicting Sovereignty: Lebanon’s Housing Tenants from Citizens to Obstacles”, and co-directed “Beyhum Street: Mapping Place Narratives”. She is also a graphic design instructor at the Lebanese University.

Close

Close