A window into Mauritian Housing Policies

By Shaz Elahee, on 14 July 2023

This housing story follows my Mum’s journey. It provides valuable insight into the history of housing policies in Mauritius and how they have evolved. Given Mauritius’ location, it is prone to cyclones that cause devastation to homes, which made it critical for the government to prioritise better structures to address inadequate dwellings. However, as my Mum’s story will illustrate, government schemes were not always accessible, resulting in more informal community financing schemes. Incremental approaches to housing development were widespread in Mauritius alongside gradually diminishing access to public spaces due to government policies prioritising real estate development. I will explore these wider factors throughout her story.

Growing up in Triolet

The story is set mostly in Triolet, a small town in post-independence Mauritius, beginning in 1972 and ending with her leaving Mauritius in 2002. Mum was the eldest of five, living with her parents and grandmother on inherited land. Mum’s grandfather adopted her father after he lost his parents as a child, and the land was divided between Mum’s father and his step-sister. This was unusual, as land and property were commonly inherited and split between male family members only, whilst women tended to marry and move in with their husband’s parents. This exception may have occurred because Mum’s aunt was a young widow with children to care for. Furthermore, Mum recalls that “people often lived close to relatives and it was common to extend the homes when the families grew, if there was space.” Although the Mauritius Town and Country Planning Act (1954) outlines that permits are needed for housing construction, it was not strictly enforced. Mum recalls that planning permission for home extensions or improvements was informal and usually involved seeking permission from relatives who lived in the surrounding area.

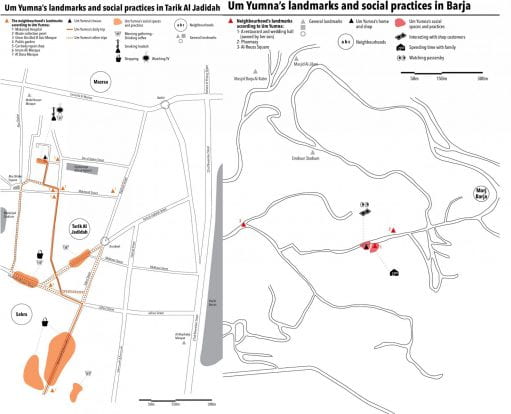

Mum’s earliest memories were of her home consisting of “two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a toilet.” They stood as three separate structures built with corrugated iron roofs and wood. Mum remembers several cyclones that particularly affected Triolet and nearby areas, some leaving a trail of housing destruction in their wake. However, Mum’s experience was again uncommon, as homes built with corrugated iron sheets and timber frames had decreased significantly during the 1970s (Chagny, 2013, p.6). Destructive cyclones in the 1960s led to workers being offered interest-free loans to build concrete houses for “personal occupation” (Ministry of economic planning and Development, 1986). As a result, housing structures improved drastically. For example, in 1960, 60% of housing in Mauritius was substandard, with only 4% considered durable; by 1972, only 7% were considered substandard, with around 40% considered durable (ibid). Mum’s experience may have been the exception because she lived in a rural area which may have been overlooked because it was not a highly commercial area and so was deprioritised for funding.

Image: Triolet 1972, side of house showing wooden structure

It is worth mentioning that there is a limitation in obtaining region-specific data, as Mauritius is a small country, and figures for smaller rural areas away from economic centres are not readily available. Hence, country-wide data has been used instead of data specific to Triolet.

Building a stronger home

In 1980, Cyclone Hyacinthe severely damaged Mum’s home. During this time, Mum’s family decided to rebuild with cement and bricks to withstand severe weather conditions better. Unfortunately, the family didn’t qualify for the government scheme providing interest-free loans to workers for constructing concrete houses for personal use (Chagny, 2013, p.7; Ministry of Economic Planning and Development, 1986) because my Mum’s dad, an informal sugarcane worker, did not have the relevant documentation.

Therefore, to finance the repairs and future improvements, they relied on an informal community financing practice known in Creole as a “sit.” A “sit” involved pooling money from numerous people (relatives and friends) in a neighbourhood into a general fund. This fund could be used for household expenses, but many used it to improve or repair homes. Every month, each household would pay the same amount into the pool, and a designated collector would distribute the pool to one household randomly until all households had received the pool at least once and then the cycle would start again.

In contrast to bank loans, the “sit” was an attractive alternative since it was interest-free. This arrangement was helpful for Mum’s family, who couldn’t provide an acceptable form of collateral to banks, lacked a credit history, and had limited awareness of how formal credit systems worked. Unlike formal bank loans, “sits” didn’t require collateral or have transaction costs (Karaivanov & Kessler, 2017). However, these practices had downsides. For example, if a ‘sit’ participant can’t pay into the fund for one month, it could impact their relationship with everyone in the community, having a high social cost (ibid). Mum recalls that contributors could swap with the weekly recipient if they required the fund earlier for an emergency, and if someone couldn’t pay for a particular month, they could work out an arrangement with the collector and contributors. It was a system built on trust; in Mum’s experience, “there were never any major issues, and it was essential in difficult times.”

The prevalence of informal community financing practices highlights the failure of government schemes to trickle down to low-income people in rural areas who may have owned land but required financing for materials to build adequate and sustainable homes. So, although private ownership was high, for example, in 1972, 94.6% of all housing units were privately owned (Ministry of Planning and Development, 1986), Mum’s experience illustrates that people that needed suitable and adequate housing were effectively left unsupported by the government.

Continuing home improvements

In 1981, Mauritius was challenged by a sugar crop failure coinciding with a global price drop (Gupte, 1981). Mum’s dad owned a piece of inherited land where he cultivated sugar cane, and the family heavily depended on this for their household income. The poor harvest and lower market prices, left the family significantly impacted; finding themselves relying on Mum’s grandmother’s pension. This also halted their much-needed home improvements and repairs. The country’s economy, which was still heavily reliant on sugar exports, also suffered detrimentally, with nearly 60,000 out of 960,000 people unemployed (ibid).

In late 1981, Mum’s dad secured a job working for the government as an irrigator, qualifying him for an interest-free government scheme to help workers improve their housing structures, with 3,000 rupees a month offered towards sturdy building materials. Mum told me “It was not much, but it was something. We would use this to buy some materials and build slowly.”

For Mum’s family, constructing their home was a slow and steady operation. Even with the government loan, building materials had to be accumulated over a considerable period before construction could start. The family continued participating in the ‘sit’, hoping it would come in handy in speeding up construction work.

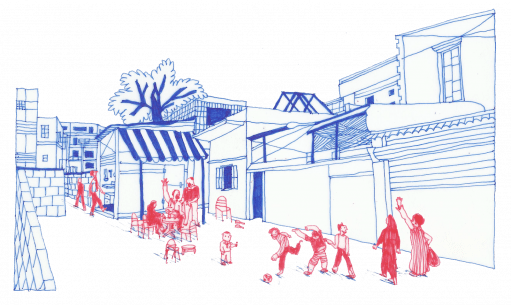

In late 1982, they started rebuilding the two bedrooms using bricks and cement, but since they couldn’t afford to hire ‘masons’ (Creole for builders), they employed a ‘maneve’ (builder’s apprentice) who required a smaller fee. It was customary for unpaid male household members and relatives to help with construction, some even travelling from far-away areas to help. To show appreciation for their hard work, they’d be offered a nice meal at the end of the day in lieu of payment. This approach was present in many other households; Mum recalls her dad and brothers helping build and improve relatives’ homes too.

The improvements were focused on the house structure whilst the kitchen and toilet remained outside, still made of corrugated iron and wood. Mum recalls the unpleasantness of bathing in winter and the frequent water shortages; using a ‘dron’ (large plastic barrel) to collect rainwater for showering. Eventually, the kitchen was added as an extension to the concrete home. Mum says the kitchen and bathroom were not prioritised because of a lack of infrastructure for sewage or freshwater, and she says “improving the bedrooms first made sense as it benefitted everyone in the house.”

This incremental approach to housing allowed Mum’s family to improve their homes based on their needs and resources. It also made high building costs more affordable. However, these small loans also meant slow progress. Hence, combining the government loans with the informal community financing was crucial to making this approach possible at all and was ultimately borne out of necessity.

Image: Triolet 1984, Mum’s home under construction using sturdier materials

Scarce land and the rise of real estate development projects

The declining price of sugar and the phasing out of preferential trade agreements for sugar exports to the EU led the government to seek alternative sources of economic revenue (Gooding, 2016). Hence, in 1985, the government initiated various real estate development projects to attract foreign investment (ibid). These legislative changes would accelerate into the 2000s with the Integrated Resource Scheme (IRS) in 2002, increasing the purchase of villas and hotels, particularly by white Europeans and South African investors (ibid) and the amended Immigration Act in 2002, allowing non-citizens to become residents if they invested a minimum of 500,000 dollars in a set of “identified business activities” (ibid).

These schemes resulted in properties that were commonly located along the coast, providing direct beach access and amenities such as wellness centres and golf courses, and so accordingly requiring vast amounts of land. While many resorts were erected around rural towns, little development or investment occurred nearby in Triolet itself. Indeed, these schemes led to unequal distribution of economic benefits. For example, tourists visiting Mauritius spent money on foreign-owned resorts and hotel restaurants. They were unlikely to venture further and spend on local businesses; thus, the local communities did not feel the economic benefits. (Ramtohul, 2016). Moreover, opening the real estate sector to foreigners caused discontent among the local population, given the sensitivity of land ownership in Mauritius due to land scarcity (Tijo, 2013; Gooding, 2016).

These coastal development initiatives also impacted local communities’ ability to access beaches. Despite it being enshrined in law that all beaches in Mauritius are public up to the high tide mark (Pas Geometriques Act, 1895), hotels and resorts built barriers that made it challenging for people to access the whole beach area. Wealthy investors and private owners who had bought homes with easy beach access followed the hotels barrier-building example and with little intervention by the government, were tacitly allowed to continue this exclusionary practice.

Going to the beach is a celebrated space, important to many Mauritians of different backgrounds who would head there on weekends. Indeed, it was one of the few public spaces available for leisure activities. For Mum, there were no gardens or play areas where she lived. Only a small plot of land behind Mum’s house was shared with her aunt to cultivate papaya trees and aubergines, and the family collectively shared the crops. Like many Mauritian families, they would walk to the beach on weekends. She recalls as she grew older, access to these spaces became more difficult due to the increasing number of resorts, hotels and holiday homes. Accessibility to these public spaces became a huge social issue. Mum recounts her and her family being “told to move from the beach near the hotels. We were made to feel really uncomfortable for sitting on the sand.”

The need to diversify its economic portfolio meant Mauritius focused on expanding the real estate industry as an alternative source of revenue. Unfortunately, the development of coastal areas led to unequal distribution and access to land and limited benefits for working-class communities. The government did not properly consider how these policies would negatively affect the livelihoods of local communities, instead choosing to prioritise scarce public spaces such as beaches for tourists and hotels only (Naidoo & Sharpley, 2015).

Moving to Vacoas

In 1994, Mum married and relocated to Vacoas, a town in the western part of Mauritius. Vacoas was a middle-income residential area closer to economic centres than Triolet. There were more amenities, and the area was generally more developed.

She shared a home with her in-laws, my dad’s brother, his wife, and their children. Similar to Triolet, the house was surrounded by the homes of my dad’s relatives, as my grandfather’s brothers owned properties on either side and in front of the house. Similarly, the male siblings all inherited the land from their father. From 1995 onward, their properties would also expand to include their sons once they married.

In 1999, Mauritius was faced with a drought, leading to a limit in water usage for most people in the country (The New Humanitarian, 1999). People had access to water for only one hour a day (ibid). Mum recalls this and says that “during that hour, each household would collect water and fill as many containers as possible.” Despite an improvement in Mauritius’ economy during this period, infrastructural issues still affected people’s daily lives, particularly women, who were expected to manage household chores, and care for young children.

Cultural housing practices continued throughout this period, whereby male family members inherited land, and women did not. After my grandfather died in 2000, the house was divided according to this practice. My dad’s brother began constructing a separate housing unit upstairs, eventually moving there after construction was completed with his family. The main house was split in two, with my dad and his older brother each inheriting half. These patriarchal housing practices can leave women without security, and a lack of land ownership can result in limited say in household decision-making (Archambault & Zoomers, 2015, pp5). It can expose women to vulnerabilities, such as finding it more difficult to leave their spouse if they experience domestic violence (ibid). It’s important to note that, as mentioned previously, if women were widowed or the family didn’t have sons, then the women would likely inherit property. Nevertheless, it is a practice that is ultimately unfavourable to women, leaving them insecure and effectively dependent on male household members; as a result, reinforcing gender inequalities.

Conclusion

In 2002, my dad found a job in the UK, and shortly after, Mum and I moved here for a new beginning. Mum’s housing story illustrates how Mauritius’ housing policies evolved rapidly from 1972-2002. It highlights how the devasting effects of cyclones meant the government had to push for the elimination of structures that could not withstand them. Although this can be lauded, due to the significant rise of concrete structures due to government schemes which provided affordable loans for workers to build sturdier homes; its inaccessibility, particularly for people living in rural areas, meant they had no choice but to rely on informal community financing schemes. The story also highlights the prevalence of patriarchal cultural housing practices whereby male family members inherited land at the expense of women, reinforcing gender norms. Finally, although the expansion of the real estate industry benefited the economy, it came at a cost for locals, who effectively lost their access to much-needed public spaces in favour of hotels, resorts and holiday homeowners in a country where land was already scarce.

Bibliography

Archambault, Caroline S. & Zoomers, Annelies. (2015) Global trends in land tenure reform: gender impacts, Taylor & Francis

Brautigam, Deborah (1999) “Mauritius: Rethinking the Miracle.” Current History 98: 228-231.

Chagny, Maïti (2013) Overview of social housing programs Effected in Mauritius since the 1960s by the government, private sector and NGOs, http://nh.mu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Report-Overview-Social-Housing.pdf

Couacaud, Leo (2023) From plantations to ghettos: The longue durée of Mauritius’s former slave population, History and Anthropology, DOI: 10.1080/02757206.2023.2183398

Friedmann, John (2005) Globalization and the emerging culture of planning,

Progress in Planning, Volume 64, Issue 3, 2005, Pages 183-234, ISSN 0305-9006,

https://doi.org/10.1016j.progress.2005.05.001. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305900605000607)

Gooding, Tessa (2016) Low-income housing provision in Mauritius: Improving social justice and place quality, Habitat International, Volume 53, Pages 502-516, ISSN 0197-3975, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.12.018. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197397515300898)

Gupte, Pranay, B. (1981) DEPENDENCE ON SUGAR WORRIES MAURITIUS, Dec. 26, Section 2, Page 38, The New York Times archives https://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/26/business/dependence-on-sugar-worries-mauritius.html

Karaivanov, Alexander and Kessler,Anke (2018) (Dis)advantages of informal loans –Theory and evidence, European Economic Review, Volume 102, Pages 100-128, ISSN 0014-2921, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.12.005.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292117302258)

Naidoo, Perunjodi and Sharpley, Richard (2015) Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius, available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/12939

Ramtohul, Ramola (2016) High net worth migration in Mauritius: A critical analysis, Migration Letters, Volume: 13, No: 1, pp. 17–33

Salverda, Tijo (2013) Balancing (re)distribution: Franco-Mauritian land ownership in maintaining an elite position, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 31:3, 503-521, DOI: 10.1080/02589001.2013.812455

Ministry of economic planning and development – central statistical office (1986) 1983 Housing and population census of Mauritius: households and housing needs: estimates and implications https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/Documents/Census_and_Surveys/Archive%20Census/1983%20Census/Analytical%20Reports/1983%20HPC%20-%20Vol.%20III%20-%20Households%20and%20Housing%20needs%20-%20Estimates%20and%20Implications%20-%20Island%20of%20Mauri.pdf

The New Humanitarian (1999) Water restrictions introduced, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/report/10166/mauritius-water-restrictions-introduced

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2011) Housing the Poor in African Cities, Quick Guide 5: Housing Finance https://www.citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/Quick%20Guide%205%20-%20Housing%20Finance%20-%20Ways%20to%20Help%20the%20Urban%20Poor%20Pay%20for%20Hpusing_0.pdf

Mauritius Local Government Act 1989 https://la.govmu.org/downloads/LGA%201989.pdf

The Town and Country Planning Act 1954 https://business.edbmauritius.org/wps/wcm/connect/business/f27c44b5-c3d7-4c9a-ae12-9e502c26b390/THE+TOWN+and+COUNTRY+PLANNING+ACT+1954.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&ContentCache=NONE&CACHE=NONE

Mauritius Building and Land Use Permit Guide https://la.govmu.org/downloads/Blp%20Guide%20Updated.pdf

Pas Geometriques Act, 1895 https://attorneygeneral.govmu.org/Documents/Laws%20of%20Mauritius/A-Z%20Acts/P/PAS%20GÉOMÉTRIQUES%20ACT%2C%20Cap%20234.pdf

Close

Close