Ever since Rasini approached me with hope, inquiring about possibly obtaining affordable housing for her family, her story has left a lasting impression. Rasini’s story represents one among countless others striving to achieve the dream of homeownership. This essay delves into the experiences of Rasini and her parents to examine the dynamic of Jakarta’s housing market over a 40-years span. In this essay, the housing narrative of Rasini’s family is followed by relevant housing policies or housing market transitions that contribute to this dynamic. The timeline is divided into two eras; Rasini’s parents and Rasini’s.

First Generation: Rasmani & Nursiah (1980 to 2008)

The dynamics of housing in Jakarta are closely tied to the massive migration that took place when the city emerged as the economic centre of Indonesia after gaining independence. The population of Jakarta grew significantly after the 1960s, from 823.000 in 1948 to 3.5 million in 1965 (Cybriwsky and Ford, 2001). This rapid urbanization was driven by the Indonesian public’s perception of improved job prospects in the capital, offering the potential for an enhanced family economy compared to opportunities in their hometowns. However, the government’s focus on constructing high-rise buildings and large complexes of government offices led to the neglect of housing provisions for the growing population.

“It was impossible for Mom and Dad to obtain a mortgage because it is cos,tly and considering their job status. That is why they had to save for years, work two shifts daily, and not have a car or motorcycle. I remember there were weeks our meals consisted of nothing but rice and salt. My parents were determined to achieve their dream of homeownership.” – Rasini.

Both of Rasini’s parent was born during that time to a working-class family that had recently migrated to Jakarta. Their limited education restricted their employment opportunities, forcing them to rely on low-paying jobs. Rasini’s dad, Rasmani, worked as an outsourced employee at the Local Administrative Office, and Rasini’s mom, Nursiah, worked as a cleaning service in a private company. After each experienced a failed marriage, they married each other in 1983. There was little information about their housing condition during the early years. However, it is known that they both resided in Rasini’s Grandparent’s housing in Central Jakarta until they obtained their home. Realising the dream of becoming homeownership was difficult for them, especially with eight children to feed. They also experienced a burden due to the social belief in Indonesia that a family must have a house to raise children (Tarigan, 2017). This context sheds light on the numerous sacrifices they made to pursue homeownership.

During that time, there was a massive construction of new towns around Jakarta’s periphery aimed at the middle and upper-income groups, as they were only accessible by private cars (Firman, 2004). The development of new towns was not based on proper spatial planning but rather driven by the profit-seeking of the developers, resulting in low-density housing with significant impacts on uncontrolled urban sprawl and price speculation practice (Firman, 2004; Leaf, 1994). In certain newly developed towns, the State Housing Provider Agency (PERUM PERUMNAS) partnered with private developers to guarantee that a portion of the housing was aimed at accommodating families with low to middle incomes (Cybriwsky and Ford, 2001). On top of that, the Indonesian government also provided interest rate subsidies for buyers through Bank BTN, reducing the interest rate from 24% to 9-15% (Winarso and Firman, 2002; Struyk, Hoffman, and Katsura, 1990).

However, This type of housing option was not a viable option for Rasini’s parents due to these factors: (1) Their outsourcing jobs were not recognized as a reliable source of income for mortgage instalments, making that housing unaffordable without a mortgage; (2) The considerable distance between housing and workplaces, coupled with the lack of public transportation, meant relocating would also necessitate finding new employment—a challenge considering their job experiences and qualifications; (3) As working parents, they relied on their parents to help in taking care for their children. Resigning from their jobs was not feasible, as it would mean sacrificing one of their income sources. These problems, faced by Rasini’s parents, are a clear representation of the structural obstacles that low-income households encounter when trying to access affordable housing. Furthermore, they highlight how the housing policies in place at the time failed to accommodate the diverse needs of different socio-economic groups, thereby amplifying these barriers.

In 1991, Rasmani and Nursiah purchased their first house, an unexpected stroke of luck. The house, measuring 80 sqm, was purchased for IDR 100,000,- below market rate, as the previous owner urgently needed funds. Although it required extensive renovations, the location was perfect for the couple as it was conveniently situated near Rasini’s grandparents’ house. Three years after purchasing the house, the first renovation was done to divide the available space into three bedrooms. As their children grew older and needed more personal space, another renovation took place three years later, adding a second floor and two more bedrooms. The incremental renovations continued into the next decade, with Rasmani and Nursiah allocating a portion of their salaries for this purpose. To minimise construction costs, they either undertook the renovations themselves or hired neighbours on an hourly wage basis.

Coincidentally, The period from 1993 to 1996 can be characterised as the first boom in Indonesia’s housing market (Firman, 2000); unfortunately, this condition was short-lived due to the economic crisis that hit Indonesia in mid-1998. This crisis led to a decline in the rupiah exchange rate, a significant decline in GDP, and a surge in layoffs. Consequently, numerous new housing projects were left unfinished, although many developers had overinvested in them. This situation benefited a select group of wealthy individuals while the rest of the nation bore the brunt of the economic chaos (Firman, 2004). Nevertheless, the housing market began to recover in early 2002, experiencing a surge in housing sales and increased property prices (Firman, 2004). This recovery, likely spurred by the 1998 economic crisis, which led to a depreciation in the rupiah’s value, caused the Indonesian public to seek safer investments like property to protect themselves from rising inflation. This growing demand is evident in the cumulative 56.82% increase in property prices from 2002 to 2008 (Bank Indonesia, 2008, as cited by Widianto, 2022). Yet, it is important to note that not all families experienced this recovery positively. For instance, the Rasini family faced hardship when Rasmani passed away in 2003, leaving Nursiah to provide for their eight children independently. At this juncture, the family house became not only a source of security (an emplacement for the family), but also a potential economic asset. It was during this time that Nursiah was faced with a hard decision.

“Beginning in 2005, my neighbors started putting their houses up for sale. Prospective buyers were offering bids as high as 15 million rupiah per square meter. Despite our pressing financial needs, my mother made the difficult decision not to sell our home. She knew that finding another affordable option capable of accommodating our entire family would be nearly impossible. Housing in Jakarta had become out of our reach and we had already quite comfortable with our surroundings. However, today, the neighbourhood around Mom’s house is filled with rental rooms.” – Rasini.

Nursiah’s decision to retain the house underscores the complexity of housing issues among low-income families. For them, the need for immediate stability and security often outweighs potential future economic gains. Nursiah prioritised housing security, for she didn’t have any other options left for her large family. Her decision had consequences; her children could not pursue a university education. This highlights the difficult trade-offs families often face between fulfilling their housing needs and ensuring their members’ well-being. Realistically, It fell upon individual households like theirs to make these tough decisions based on their unique circumstances, priorities, and resources for their long-term interest and overall welfare.

As the neighbourhood transformed into rental rooms closely related to real estate investment, it was even more challenging for long-term residents like Nursiah. The distinct characteristic between long-term residents and rental room occupants led to disparities in community engagement and neighbourhood cohesion. With rental room residents being more transient and less committed to community involvement, long-term residents like Nursiah experienced feelings of isolation and disconnected from their surroundings. This shift in neighbourhood dynamics could impact the overall well-being of long-term residents and erode the social fabric that once held the community together.

Second Generation: Rasini (2008 – Now)

“It reached a point where Mom’s house became increasingly overcrowded, so after my second child was born, we moved to Rumah Petak. The house is small, with no visible partitions between rooms, so we had to create our own dividers using cabinets or curtains to make it feel more like a home. But at that time, it was the only option we could afford.” – Rasini

Rasini and her husband married in 2008 and decided to rent a Rumah Petak in West Jakarta after their second child were born in 2011. Since Rasini’s husband earned a minimum wage of IDR 1,150,000 as a security staff member, the Rumah Petak, priced at IDR 500,000, was their only viable housing option. Rumah petak (cheap rental house) is a type of residential dwelling consisting of a large building divided into many small rooms, most of which are located in the Kampung area. In Rasini’s case, their unit has a rectangular room measuring 3×9 meters without wall separations. Then, she divided the area into two bedrooms, one kitchen, and one bathroom. Rumah petak is particularly popular among migrants or low-income households in metropolitan cities. Although Rasini is the homeowner’s child, the inheritance or wealth transfer theory using housing as an asset is impossible due to Nursiah’s eight children. Dividing the property fairly becomes more complex in a large family, potentially leading to disputes. Consequently, Rasini must find a solution to address her family’s housing needs.

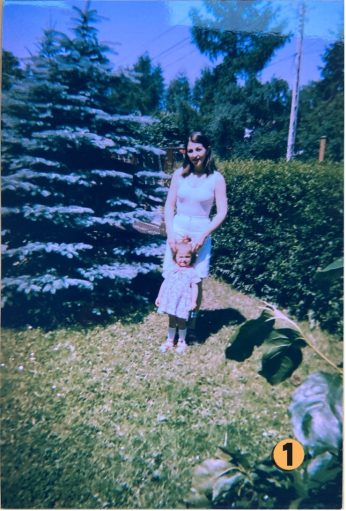

Figure 1. Rumah Petak where Rasini’s Family Lived (Source: Rasini, 2023)

Rasini’s husband worked in Cikarang, West Java, which meant he could only visit his family on weekends while staying at a company dormitory during the week. In 2013, he resigned from his job to become a street vendor selling sandals and shoes after saving up enough money to start his business. This decision was primarily motivated by Rasini’s struggles managing childcare and growing household expenses. Since income as a street vendor fluctuates, Rasini decided to work as a cleaning service, earning her the minimum wage (IDR 2,200,000), while her husband took up a second job as an Ojek Pangkalan (Indonesia’s motorcycle taxi rental). Their educational background, which is high school graduates, restricted their job opportunities, making it challenging for them to have financial security. Unknowingly, this limitation also influenced their housing options, demonstrating the interconnected nature of education, employment, and housing stability in urban environments.

“Rent is getting more and more expensive, so I started thinking about buying a house instead of constantly spending money on rent without owning anything. Ideally, I would like a house near my parents, but now it’s impossible. Now the price of a house near my mother’s house is up to 30 million rupiah per meter.” – Rasini

As the rent for Rumah Petak reached Rp 1,500,000/month in 2019, Rasini began considering homeownership, ideally close to Nursiah’s residence in Central Jakarta. However, that year, housing prices in Nursiah’s house had soared to IDR 30,000,000 per meter. Elmanisa et al. (2016) found that developers’ speculative practices in Jabodetabek contributed to soaring property prices counted by 50% between 2010 to 2014. Jakarta’s housing development focus on low-density, landed houses exacerbated the situation, causing land scarcity. This can be traced back to the aggressive new-town developments of the 1990s, when large developers targeted premium areas area Jakarta for luxury landed-housing projects, relegating affordable housing options to the outermost regions of the Bodetabek[1] area. The impact of these trends is visible in the dramatic disparity in land prices across the city as discovered by Elmanisa et al. (2016). Land prices in Central Jakarta, where Nursiah’s residence is located, reach their peak. As one moves further away from this central area, the prices gradually decline, illustrating a clear gradient in property costs. This particular distribution of land prices exemplifies the economic forces at play in shaping the city’s urban landscape. Consequently, due to her financial constraints, Rasini found it increasingly challenging to find affordable housing near Nursiah’s home.

At that time, Rasini worked in an environment where she was exposed to extensive information about the government’s housing assistance program or KPR FLPP, which became her primary motivation for choosing this path. The KPR FLPP, or housing financing liquidity facility, is part of President Jokowi’s “Sejuta Rumah” (One Million House) initiative to improve affordability and homeownership among low-income households. Through this program, eligible first-time homeowners can obtain low-interest mortgages (5%) to purchase newly built affordable homes from developers. The monthly instalments for the Jabodetabek area range between IDR 950,000 – 1,200,000, with housing prices IDR 168,000,000. However, these affordable housing options have a trade-off: Low-quality units, low-transport accessibility, and inadequate infrastructure. Harrison (2017) highlights several problems with affordable housing units in Indonesia, such as the distance from employment opportunities and public amenities, lack of connection to the local water and electrical system, and seasonal flooding due to poor irrigation systems. These issues lead to the big question of whether the government’s homeownership target is truly addressing the housing needs of the majority or not.

Figure 2. Location comparison between Rasini’s new home, rumah petak, office, and Nursiah’s home.

After some delays in purchasing a house due to the Covid-19 case, Rasini finally purchased a 36 sqm house through the KPR FLPP program in mid-2022. She provided a down payment of IDR 6,500,000, which she paid off over four months, resulting in a mortgage instalment of IDR 1,080,000 for 20 years. The area where Rasini’s new home is not fully developed, with limited access to public amenities. It was 54 km from Rasini’s workplace, with a one-way commute taking 2 to 3 hours. This adds to the challenges Rasini and her family face, as they must deal with the long daily commute and the continuity of her husband’s business.

“We haven’t fully figured out everything that will come after moving. I’m just really hoping the current area will become more developed, so my husband’s plan to open street-stall in there can become a reality and help increase our family’s income.” – Rasini

Adamkovič and Martončik’s (2017) theory highlights the negative link between poverty and decision-making, with a preference for short-term rewards over long-term consequences among this group, which may perpetuate the cycle of poverty. In Rasini’s case, her decision to buy a house farther away from her main activity area is driven by her inability to determine the best choice between long-term consequences (long commute time, increased expenses, and impact on her work-life balance) and the need for a short-term solution (an affordable housing). Her financial constraints create a heavy cognitive load on psychological states, such as stress, uncertainty, and distress. As a result, This mental pressure impacts her impulsive decisions based on intuitive thinking, prioritizing short-term solutions over potential future outcomes. This pattern contributes to the cycle of poverty perpetuation as Rasini’s family’s inability to save money.

Despite Rasini’s new home being completed in early 2023, she postponed her move due to the unavailability of elementary schools for her children in the area. This situation certainly adds to Rasini’s financial burden, as she now has to manage both the mortgage instalment and housing rent. However, given the limited options available to her, Rasini finds herself with no choice but to bear the additional expenses.

Figure 3. Life size mock-up of Rasini’s new home (Source: Delta Group Property, 2020)

Addressing The Housing Dilemma

The housing dilemma faced by Rasini’s Family across two generations provides critical insights into the challenges and complexities low-income families face in navigating Jakarta’s housing market. The struggle to secure housing differs in each generation, which shows how Jakarta’s housing market shifted in a different era.

The Nursiah and Rasmani’s experienced the early stage of housing inequalities stemming from inadequate policies and profit-driven developments. As Jakarta transformed into a bustling metropolis, the availability of affordable housing failed to meet the demand, and existing options did not adequately cater to diverse needs. Consequently, low-income families faced immense struggles and relied on resilience and luck, as evidenced by them. Although they were fortunate enough to purchase a house before the price boom, they could not provide their childer with a high level of education due to limited resources left, thereby perpetuating the cycle of poverty and limiting their children’s opportunities for social mobility.

Despite the government’s efforts to implement new housing policies targeting low-income families in Rasini’s era, the ripple effects from past policy inadequacies were increasingly apparent. Rasini like most younger people in Jakarta, faced the harsh reality that securing housing within the inner city had become increasingly difficult. Housing options in the outskirts Jakarta, while not so affordable, are lacked proper infrastructure and basic amenities. This situation forces families like Rasini’s to make difficult trade-offs between affordability and access to resources, such as schools, a well-connected transportation system, and employment opportunities. Consequently, this exacerbates the urban segregation and social inequalities that plague Jakarta, as low-income families are pushed further away from the city centre and the opportunities it presents.

To address these issues, policymakers should re-evaluate and adjust policies to accommodate diverse needs while tackling past inadequacies by improving infrastructure for housing development on the outskirts. Furthermore, reconsidering the emphasis on homeownership is crucial, as it perpetuates neoliberal ideologies. Instead, promoting affordable rentals, cooperative housing, and community land trusts can offer secure living conditions without long-term financial burdens for this sector. By diversifying housing solutions, policymakers can challenge prevailing neoliberal narratives and work towards creating a more equitable and inclusive housing market that serves the needs of all citizens, regardless of their socio-economic status.

Bibliography

Adamkovič, M. and Martončik, M. (2017) ‘A Review of Consequences of Poverty on Economic Decision-Making: A Hypothesized Model of a Cognitive Mechanism’, Frontiers in Psychology, 8. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01784 (Accessed: 19 April 2023).

Arif Widianto (2022) Data Indeks Harga Properti di Indonesia, Bolasalju.com — Riset dan Edukasi Investasi. Available at: https://www.bolasalju.com/artikel/data-indeks-harga-properti-di-indonesia/ (Accessed: 11 April 2023).

Cybriwsky, R. and Ford, L.R. (2001) ‘City profile: Jakarta’, Cities, 18(3), pp. 199–210. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00004-X.

Dao Harrison (2017) Five lessons on affordable housing provision from Indonesia. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/five-lessons-affordable-housing-provision-indonesia (Accessed: 21 April 2023).

Delta Group Property (2020) ‘Housing features of Puri Delta Kiara – Type 28/60’, Delta Property. Available at: https://deltaproperty.co.id/property/puri-delta-kiara-tipe-28-60/ (Accessed: 12 April 2023).

Elmanisa, A., Kartiva, A., Fernando, A., Arianto, R., Winarso, H. and Zulkaidi, D. (2016) ‘LAND PRICE MAPPING OF JABODETABEK, INDONESIA’, Geoplanning: Journal of Geomatics and Planning, 4, p. 53. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14710/geoplanning.4.1.53-62.

Firman, T. (2000) ‘Rural to urban land conversion in Indonesia during boom and bust periods’, Land Use Policy, 17(1), pp. 13–20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(99)00037-X.

Firman, T. (2004) ‘Major issues in Indonesia’s urban land development’, Land Use Policy, 21(4), pp. 347–355. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2003.04.002.

Leaf, M. (1994) ‘The Suburbanisation of Jakarta: A Concurrence of Economics and Ideology’, Third World Planning Review, 16(4), pp. 341–356.

Struyk, R.J., Hoffman, M.L. and Katsura, H.M. (1990) The Market for Shelter in Indonesian Cities. Urban Institute Press.

Tarigan, S.G. (2017) Housing, homeownership and labour market change in Greater Jakarta, Indonesia. Thesis. Newcastle University. Available at: http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/3795 (Accessed: 10 April 2023).

Winarso, H. and Firman, T. (2002) ‘Residential land development in Jabotabek, Indonesia: triggering economic crisis?’, Habitat International, 26(4), pp. 487–506. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00023-1.

[1] The term “Bodetabek” stand for Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi is an acronym used to describe the urban agglomeration that extends beyond Jakarta’s city limits and includes its surrounding satellite cities.

This housing story is part of a mini-series revealing the complex ways in which personal and political aspects of shelter provision interweave over time, and impact on multiple aspects of people’s lives. Space for strategic choice is nearly always available to some degree, but the parameters of that choice can be dramatically restricted or enhanced by context. The wide range of experience presented in this collection shines a light on the wealth of knowledge and insights about housing that our students regularly bring to the DPU’s learning processes.

Close

Close