Dem Bones, Dem Bones, Dem Dry Bones … Excavating Memory, Digging up the Past

By Gemma Angel, on 16 July 2012

by Katie Donington

by Katie Donington

Above all, he must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil. For the ‘matter itself’ is no more than the strata which yield their long-sought secrets only to the most meticulous investigation. That is to say, they yield those images that, severed from all earlier associations, reside as treasures in the sober rooms of our later insights – like torsos in a collector’s gallery.[1]

The Buried on Campus exhibition at the Grant Museum ran from April 23rd to July 13th 2012. Following the 2010 discovery of human remains beneath the Main Quad of UCL, research was undertaken to determine the reason for their presence. Forensic anatomist Wendy Birch and forensic anthropologist Christine King, members of the UCL Anatomy Lab, were able to date the bones which were over a hundred years old. The bones themselves also gave clues to the reason for their presence. Several items had numbers written on them and others displayed signs of medical incisions. This led the team to the conclusion that the bones represented a portion of the UCL Anatomy Collection which had been buried at some point after 1886.

The issue of displaying human remains in a museum of zoology was discussed by Jack Ashby, Grant Museum Manager in a recent blog post:

The whole topic of displaying human remains has to be considered carefully and handled sensitively… One of the questions we asked our visitors last term on a QRator iPad was “Should human and animal remains be treated any differently in museums like this?” and the majority of the responses were in favour of humans being displayed, with the sensible caveats of consent and sensitivity.[2]

The discovery and exhibition of human remains raises interesting questions about the relationship between archaeology, history, science, memory and identity. It also links into debates over the ethics of display in relation to human beings. Who were these people? Why did their bodies end up in an anatomy collection? Did they consent or were they compelled? Is it possible or desirable to attempt to retrieve or reconstruct the object as subject?

The case of the bones buried on campus reminds me of another example in which the physical act of excavation was transformed into an act of historical re-inscription. In 1991, workmen digging the foundations of a new federal building close to Wall Street uncovered the remains of 419 men, women and children. Archaeologists, historians and scientists were called in and they were able to identify the area as a 6.6 acre site used for the burial of free and enslaved Africans by examining maps from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The bones offered specific information which helped to give a partial identity to the people interred. Using ‘skeletal biology’[3] it was possible in some cases to pin point where in Africa individuals had come from – Congo, Ghana, Ashanti and Benin, as well as revealing whether they had been transported via the Caribbean. Bone analysis spoke of the appalling conditions of slavery; fractured, broken, malformed and diseased bones articulated stories of unrelenting labour, nutritional deficiency and coercive violence.

Objects found inside some of the burials created a sense of the uniqueness of each person as well as the care taken by loved ones as they performed burial rituals. The lack of items found also indicated the social status of the majority of people buried on the site.

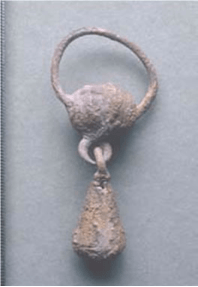

This pendant (image courtesy of the African Burial Ground Project) was recovered from burial 254, a child aged between 3 ½ and 5 ½ years old. It was found near the child’s jaw and may have been either an earring or part of a necklace. The objects and bones represented a visceral historic link to the African American community in New York. The sense of ownership they felt towards this history and the individuals who had emerged from the soil, led to active community engagement in the project. In line with the wishes of the African American community, all original items were facsimiled before being reinterred along with all 419 ancestral remains in a ceremony in 2003. A memorial and museum were also built on the site (see image below, courtesy of the African Burial Ground Project).

The emergence of the skeletons was interpreted by some as a literal rendering of the way in which America has been haunted by its relationship with slavery. As physical anthropologist Michael Blakely, who worked on the site explained; ‘with the African Burial Ground we found ourselves standing with a community that wanted to know things that had been hidden from view, buried, about who we are and what this society has been.’[4]

The context of the two sites is of course very different. However, a comparison of them does raise questions about the uses of human remains and their relationship to history, memory and identity. The bones at UCL formed part of an anatomical teaching collection; a composite of individuals whose bodies somehow became the property of medical institutions. Those people often consisted of those on the margins of society; the poor, the criminal and the exoticised ‘others’ of empire.[5] Debates over the repatriation of human remains in museum collections highlight their importance to people’s sense of identity and history. Without family or community groups to claim the individuals discovered at UCL, it seems that they are destined to remain object rather than subject – ‘severed from all earlier associations… torsos in a collector’s gallery’.

Have your say – what do you think should happen to the bones at UCL?

[1] Walter Benjamin, ‘Excavation and Memory’, in Selected Writings, Vol. 2, Part 2 (1931–1934),ed. by Marcus Paul Bullock, Michael William Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, (Massachusetts, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 576.

[2] http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/2012/04/24/buried-on-campus-has-opened/

[3] http://www.archaeology.org/online/interviews/blakey/

[4] http://www.archaeology.org/online/interviews/blakey/

[5] Sadiah Qureshi, ‘Displaying Sara Baartman, The Hottentot Venus’, History of Science, Volume 42 (2004), pp.233-257.

http://www.negri-froci-giudei.com/public/pdfs/qureshi-baartman.pdf

Close

Close