Stealing from Peter to Pay Paul: Satirising Slave Compensation in the Radical Prints of C. J. Grant

By Alicia C Thornton, on 28 August 2012

by Katie Donington

by Katie Donington

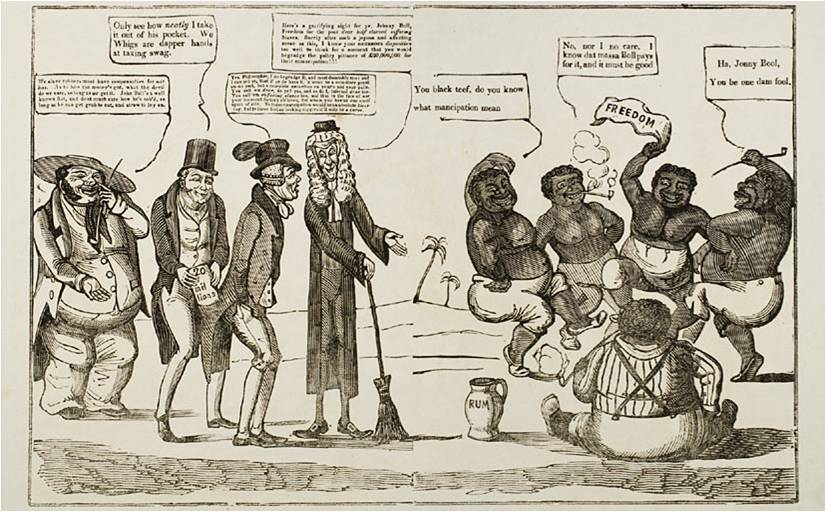

C. J. Grant, ‘Slave Emancipation; Or, John Bull Gulled Out Of Twenty Millions’, Woodcut printed and published by G. Drake, 12 Houghton Street, Clare Market, London (1833-35). Image © UCL Art Collection, UCL, EPC8032.

From left to right the caricatured figures represent a West Indian slave-owner, a Whig politician, a character called ‘John Bull’ who was used to represent the British public, an abolitionist and a crudely racialised group of enslaved people.

The captions read:

Slave-owner: ‘We slave robbers must have compensation for our loss. As to how the money’s got, what the devil do we know, so long as we get it. John Bull’s a well known flat, and don’t much care how he’s robbed so long as he can get grub to eat and straw to lay on.’

Whig politician: ‘Only see how neatly I take it out of his pocket. We Whigs are dapper hands at taking swag.’

John Bull: ‘Yes, Philosopher, I do begrudge it, and most damnably too: and I can tell ye, that if ye do have it, it won’t be a voluntary grant on my part, but a complete extortion on your’s and your pals. You call ’em dear, do ye? Yes and so do I, infernal dear. You call ’em suffering slaves too, and that in the face of our poor innocent factory children for whom you hav’nt one small part of pity. To them emancipation would be an absolute blessing, but to these bishop looking niggers it’ll only be a curse.’

Abolitionist: ‘Here’s a gratifying sight for ye, Johnny Bull. Freedom for the poor dear half-starved suffering slaves. Surely after such a joyous and affecting scene as this, I know your GENEROUS disposition too well to think that you would begrudge the paltry pittance of £20,000,000 for their emancipation!!’

1st Enslaved: ‘You black teef, do you know what mancipation mean’

2nd Enslaved: ‘No nor I no no care. I know dat Massa Bull pays for it, and it must be good.’

3rd Enslaved: ‘Ha Jonny Bull you be one dam fool.’

My PhD is attached to a major new research project – The Legacies of British Slave-Ownership Project . Launched by the History department at UCL in 2009, the project team consists of Professor Catherine Hall , Dr. Nick Draper and Keith McClelland . The team have been investigating the relationship between slave-ownership and the formation of modern Britain. In 1833 the government brokered a deal with the slave-owners to secure emancipation for the enslaved in the British West Indies. The package involved both an apprenticeship period for the enslaved as well as the payment of £20,000,000 worth of compensation to the slave-owners. In order to receive compensation people had to register their claims, this bureaucratic process left behind a comprehensive documentation of who the slave-owners were in 1838 when the lists were compiled. This data forms the empirical basis of the project which is using the information to build a publically accessible online encyclopaedia of British slave-ownership.

The C. J. Grant image is the project’s logo and is from the UCL Art Museum Collection. Printed on cheap paper and sold for a penny, the image satirises the controversial decision to pay the slave-owners compensation, depicting it as a theft from the public pocket. Grant was not alone in this view – the Poor Man’s Guardian claimed that compensation would be ‘extracted from the bones of the white slaves’ in Britain[1]. Grant’s prints were aimed at the socially and politically conscious working classes. In the image ‘John Bull’ speaks for working people but they are not represented pictorially. This is an interesting absence – with no parliamentary political representation at the time the image suggests that they could only achieve a political voice by proxy. It also demonstrates the way in which Grant perceived the working poor as being excluded from debates around slavery, freedom and labour conditions.

The largely middle class abolitionist leadership led some radicals to suggest that their concern for the enslaved in the colony led to the neglect of the industrial working poor at home. This form of what was described as ‘telescopic philanthropy’ had also been seized upon by the slave-owners. Radicals like Grant had to tread a fine line between their critique of the abolitionists, their support for emancipation and the language of the anti-abolition West India lobby. Sometimes this failed – the depiction of the enslaved in this image speaks straight to proslavery myth of the infantilised, happy and contented slave for whom freedom would be ‘a curse’.

After nearly fifty years of polarised discussion, the representation of the slave-owner and the abolitionist reflects a frustration with both the greed and gluttony of the former and the sanctimonious piety of the latter. The opulent flesh of the planter becomes a symbol for the unfettered indulgence and idleness of plantation life whilst the pinched frame and clerical garb of the abolitionist signifies the unceasing virtuous self-restraint of the morally puritanical Evangelical ‘Saints’, who alongside their campaign for abolition had also launched a reformation on the manners of the working classes.

The slave-owner stretches out his hand expectantly waiting for the government to bail him out; the knowing gesture an indication of the long-standing relationship between big sugar in the Caribbean and the government at home. The slave-owners argued that they had invested in ‘property in men’ under a system which was sanctioned and regulated by the government. By ending slavery the government was effectively confiscating their legitimate property and they were therefore entitled to compensation.

The abolitionists were divided over the issue of compensation. Some of them contested the principle that there could ever be ‘property in men’ and in doing so attempted to undermine the central tenet of slave compensation. However, at a time when property was held as sacred, some of them agreed that compensation should be paid. They suggested that as the nation as a whole had benefitted from slavery, then everyone should pay for salvation from what they described as the ‘national sin’. It was thought that paying the price of emancipation would expunge the stain of slavery replacing it instead with the image of an anti-slavery nation – liberal, benevolent and freedom loving.

Compensation for the enslaved was never seriously debated in 1833 and indeed by being forced to work for free for a further five years of apprenticeship – until 1838 – the enslaved effectively paid in part towards their own emancipation. At the ending of slavery there was no land redistribution and wealth remained in the hands of a small elite. The deeply divisive issue of reparations for slavery is one that has been raised with most nation states who were involved in the slavery business. No former slaving nation has as of yet paid any compensation to the descendants of those who endured Transatlantic slavery although it was declared a crime against humanity in 2001.

Have your say…

- Should the British government pay reparations?

- How would the process work?

- Who would the reparations be given to?

Further reading:

- Exhibition Catalogue: C.J. Grant’s ‘Political Drama’, a radical satirist rediscovered, ed. Richard Pound (UCL, 1998).

- Nicholas Draper, The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- http://www.jis.gov.jm/special_sections/reparations/ Government website looking at the reparations debate in Jamaica.

[1] Poor Man’s Guardian, 6 July 1833.

Close

Close