The Meaning of (Fossilised) Life or “If an ammonite swims in the sea and nobody’s there to see it…”

Amongst the myriad forms of life that line the walls and fill the Victorian cabinets of the Grant Museum of Zoology, there lie a number of specimens that are marked out not by the strangeness of their appearance (for the Grant is a veritable archive of strangeness, from preserved, etiolated lungfish to the infamously taxonomically confusing stuffed platypus) but by their sheer ancientness. Whereas the majority of specimens in the Grant are specimens or skeletons of animals and organisms that still exist, or that existed within recorded historical consciousness (this, this, and this), these enigmatic objects come from a time before anything resembling a human being stepped foot on the Earth. These specimens, as you may have guessed, are fossils.

Fossils at the Grant Museum

The Grant has a number of fossilised specimens in its collection and a selection of models and casts of famous fossils, the originals of which are stored elsewhere. The stories of fossils, how they come to be preserved over millions of years of geological flux, as well as the unlikely and often serendipitous ways in which they are found by palaeontologists and amateurs alike, are fascinating. Perhaps the most historically significant example is that of Mary Anning, a working-class woman from Dorset who began her fossil-finding career selling fossilized curios to seaside tourists. Over time, her skill and tenacity as fossil finder grew and led to her to the discovery of the Plesiosaurus, the Ichthyosaurus, and a number of other highly significant ancient species. Her work was in turn influential on a number of more canonical figures in the history of science such as the influential geologist William Buckland and the fossil collector Thomas Hawkins. Conversely, the pre-eminent French zoologist of the late 18th and early 19th Century, Georges Cuvier, to the detriment of his legacy, branded her a fraud.

However, there is a different type of story I want to pursue today, and it is one that might seem wilfully obscure to those of us accustomed to considering the scientific and paleontological implications of fossil finds and palaeo-archaeology more generally.

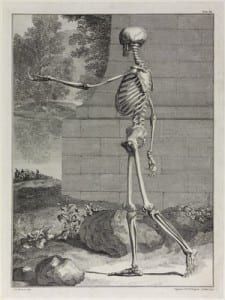

I have asked in a previous post, incited by the literary, philosophical meanderings of Ishmael in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a question that seems to me to drive right at the core of what the Grant Museum endeavoured to answer in the 19th Century: What can the structure (the anatomy, if you will) of an organism tell us about the organism itself? Robert Grant himself, in a speech delivered to his colleagues at the University of London in 1833, put it simply: ‘Comparative anatomy is that branch of physical science which treats of the structures of animals’. Ishmael, connecting us once more to UCL’s collections, asks this of the skeleton of Jeremy Bentham that now sits in the South Cloisters of the university. Bentham, according to Ishmael, conveys in his very structure the character of the utilitarian thought that he pursued in his philosophical works. For Ishmael this is the one instance in which structure and essence are undifferentiated aspects of the whole. Generally, however, he admits that ‘nothing of this kind could be inferred from any leviathan’s articulated bones’. Robert Grant may have disagreed with Ishmael on this point; but for Melville’s narrator, the question is not so much we can know the whale, but what the limits of this knowing are.

Jeremy Bentham Auto-Icon – A Utilitarian Anatomy?

Moby-Dick, being as much about the interpretation of literature and the search for truth as it is about the search for an elusive white whale asks us to consider a related question: what can the structure of a text, of a book, tell us about the text or book itself? Are there limits to our knowledge of a book or a novel? Can we ever “know” a book fully, by closely studying its parts?

We can put these questions more succinctly: What can an inanimate part (structure or skeleton) tell us about the living whole (text or organism)? Melville, via Ishmael, is circumspect about our ability to gain an accurate representation of the whole, lamenting that ‘one portrait may hit the mark much nearer than another, but none can hit it with any very considerable degree of exactness. So there is no earthly way of finding out precisely what the whale really looks like’.

Thus it is that I come finally to the question I want to pursue, a question that has been prompted by the time I spend among inanimate parts and fossilised remains, as it has by my own forays into literature and its interpretation. What does a fossil mean? What can a fossil, a part of the entire, unimaginable span of organic history, tell us about the entirety of life and history? Can it have a meaning at all? Is it the case that, as with Melville’s leviathanic skeleton, the fossil (indeed all fossils) can only tell us a limited story about the history of life on earth? And if so, what does this tell us about “meaning” as such?

Traditionally, fossils (versus the skeletons of living or recently extinct species) have acted as testaments to the vast span of organic history: subterranean monuments to the dead, which nevertheless provide us with the silent testimony of life anterior to the existence of humanity. In the case of Mary Anning, as well as the work of her detractor, Georges Cuvier, the ancient specimens they described, greatly troubled 18th and 19th century biblical accounts of creation which attributed thousands and not millions of years to the age of the earth. Beyond this, of course, a fossil tells us amazing stories about evolutionary and geological history. In the Grant, a large ammonite, a fossilised marine invertebrate similar to the contemporary nautilus genus, sits silently between the skulls of two elephants and model of an elephant’s heart. However, during the Mesozoic era, the ammonite was so abundant, that palaeontologists now can use it as an index fossil, a specimen so ubiquitous that an entire geological epoch can be characterised by its presence in the stratigraphic record. This tells us a tantalising story of a distant and unknowable watery past, an earth populated for thousands of years by invertebrate marine animals, a world that, unless we spend the majority of our time beneath the waves, is incomprehensible to us and was unimaginable without the material existence and fossilisation of the ammonite itself.

Ammonite – Grant Museum

For some, fossils fill the blanks of our evolutionary past (the ammonite, it would seem, fills a particularly large one). If one is vigilant, one will see the intermittent appearance in the pages of newspapers and popular journals stories of “missing links”. Here, the discovery of ancient proto-human remains provides us with the supposed intermediary between our species, homo sapiens, and our primitive ancestors. Strictly speaking, there is no one missing link – evolutionary history is not linear or progressive in the way we might like to think, but fossils nevertheless are employed to supply us with a meaning that underwrites humanity’s existential legitimacy, a paleontological riposte to the larger metaphysical question: Why Are We Here? Unfortunately, fossils, even ones that seem to supply us with “missing links” to our evolutionary past do not answer this question satisfactorily. Henry Gee, an editor at Nature and the author of The Accidental Species writes witheringly of the temptation to interpret evolutionary history this way: ‘The term missing link, … speaks to an idea in which evolving organisms are following predestined tracks, like trains chugging along a route in an entirely predictable way. It implies that we can discern the pattern of evolution as something entirely in tune with our expectations, such that a newly found fossil fills a gap that we knew was there from the outset. Quite apart from the impossibility of knowing whether any particular fossil we might find is our ancestor or anyone else’s, this is a model of evolution that is at once entirely erroneous, and also rather sad’. What is ‘sad’, for Gee, is the seemingly unassailable arrogance of the human species’s tendency to understand all other evolutionary phenomena in relation to the question of its own existence. After all, we have been on this Earth for a comparatively minuscule period in comparison to the ammonite, and yet, we like to see ourselves as somehow more “evolved” or “superior”, despite the increasing climatic evidence that we are hastening the end of our tenure on this Earth due to the very arrogance that underwrites our anthropocentric view of the world.

This arrogance is perhaps no surprise. We are inescapably human, trapped within our own human minds, and unable to inhabit the minds of other species. It is no surprise then that we tend to view everything through an anthropocentric prism; we are imprisoned by it. The Victorian novelist Thomas Hardy gestured at the possibility of escaping our all-encompassing humanness in his early novel A Pair of Blue Eyes, in which the fossilised past irrupts into the otherwise serene life of an otherwise confident Victorian man. In a passage supposedly inspired by the mountaineering travails of his intellectual mentor (and father of Virginia Woolf) Leslie Stephen, Hardy describes the mental state of a rich gentleman, Henry Knight, an amateur geologist, as he hangs perilously from the edge of a cliff on the Jurassic Coast in Devon. As he dangles from the cliff face, he sees a trilobite embedded in the rock before him, and his eyes meet those of the ancient crustacean his mind is cast back into deep geological and evolutionary history:

‘Time closed up like a fan before him. He saw himself at one extremity of the years, face to face with the beginning and all the intermediate centuries simultaneously. Fierce men, clothed in the hides of beasts, and carrying, for defence and attack, huge clubs and pointed spears, rose from the rock, like the phantoms before the doomed Macbeth. They lived in hollows, woods, and mud huts—perhaps in caves of the neighbouring rocks. Behind them stood an earlier band. No man was there. Huge elephantine forms, the mastodon, the hippopotamus, the tapir, antelopes of monstrous size, the megatherium, and the myledon—all, for the moment, in juxtaposition. Further back, and overlapped by these, were perched huge-billed birds and swinish creatures as large as horses. Still more shadowy were the sinister crocodilian outlines—alligators and other uncouth shapes, culminating in the colossal lizard, the iguanodon. Folded behind were dragon forms and clouds of flying reptiles: still underneath were fishy beings of lower development’.

Here an encounter with a fossil is the catalyst for a reverie concerning the unbearable morality of all that lives as well as the transience of humanity, its utter insignificance in the face of all that has gone before and all that will follow. And yet again, the fossil remains secondary to our own consideration, our own sense of humanness. In describing ‘an earlier band’ of monstrous animals, Hardy’s narrator does not fail to add ‘No man was there’. Despite the fossilised animal’s complete indifference to the existence of humanity, we repeatedly project our own existence into the way we understand it. It is a foil against which we understand our own condition.

Returning to the original question, then, what can the fossil – the fragment – tell us about the whole? Not much it seems, as it is impossible to step outside our own anthropocentrism; we are unable to escape the perceptual prison of our own humanity. Thus what the fossil can tell us about the Earth, and the history of life upon that Earth is limited by our inability to be anything but human – and subjective. However, a French philosopher named Quentin Meillasoux would argue differently. For Meillasoux, the fossil is the most revealing artefact one could wish for. Not for what it tells us about the imagined ‘whole’ to which I have referred a number of times. But of what it can tell us about how we might go about knowing the nature of reality.

For Meillasoux, the pre-human fossil has a meaning that has the potential to recalibrate the nature of the philosophy of reality itself. Meillasoux’s philosophical endeavour is dedicated to solving the Gordian knot that he – and the pre-eminent French philosopher, Alan Badiou – believe was most successfully tied by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th Century. Kant’s philosophy, Badiou states, can be said to have ‘broken the history of thought in two’. Before Kant, Meillasoux tells us, is the period of pre-critical philosophy, and afterwards, the period of critical philosophy. What do these terms mean? [Warning: This is going to get a little technical, but I promise, we’ll get back to fossils!]

A pre-critical stance towards reality, Meillasoux states, is seen today as insupportably naïve, because it requires us to believe that, despite the frailties of human perception and its inescapably subjective character, we can gain access to the very thing in-itself, that is to say, the very thing we are observing, stripped of all subjective appearances and all perceptual distortion and ambiguity. A critical stance, the philosophical stance to which the majority of philosophers adhere today, states the opposite and this – we are told – is Kant’s doing. What did Kant tell us? Meillasoux calls Kant’s central critical thesis ‘correlationism’. Correlationism, he tells us, is ‘the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from each other’. In other words, we can never access a thing, a being, without it being a function of thinking, or our perception. This has big implications, not only in philosophy, but in science too. ‘Not only does it become necessary to insist that we never grasp an object ‘in itself’, in isolation from its relation to the subject [us], but it also becomes necessary to maintain that we can never grasp a subject that not would always-already be related to an object’. In short, Meillasoux is saying that, because of this critical stance we 1) can never know anything in itself without the taint of human subjectivity or 2) ever insist that anything exists outside of a person’s ability to perceive it. For many (perhaps those of a more relaxed disposition) this is not a problem; things exist and we don’t need philosophy to tell us otherwise. But for Meillasoux, and the more masochistic of philosophers, this is a big problem. He wants to know if we can know and, if so, how we can know. He is not satisfied with the stasis of contemporary philosophical thought because it tells us, like Ishmael, that anything we know is merely an approximation of the Real. And because of this he’s going to take on Kant, perhaps the single most important figure in Western philosophy of the last 500 years. And he’s going to do it with fossils.

The oldest fossil in the Grant Museum is the Ottoia Prolifica, or as has been called in a previous blog post, the ‘Ancient Penis Worm’, the reason for which will be clear for readers of Classics and Ancient Greek. This particular fossil is inconceivably old. It dates from over 500 millions years ago – a date that for Meillasoux is extremely important. It is so crucially important because it pre-dates the arrival of humankind (Homo habilis) by around 498 millions years. In other words, this unassuming looking fossil existed almost half a billion years before human consciousness was ever even able to cast its observational, subjective eye over the phenomena of the world. Yet, we have already established that the subject-object relation is constitutive of existence itself; without the subject, the object is invisible and thus effectively non-existent. The fossil, what Meillasoux will call, ‘The Arche-Fossil’ is the material evidence to repudiate the critical stance and to make us re-think correlationism: ‘”the arche-fossil” … [represents] not just materials indicating the traces of past life, according to the familiar sense of the term ‘fossil’, but materials indicating the existence of an ancestral reality [think of the ammonites’ watery world!] or event; one that is anterior to terrestrial life’.

Ottoi Prolifica

The Ottoi Prolifica is a material instance of something – in itself – which existed before man could project its own identity and subjectivity upon all that exists outside itself, when all that existed were things in themselves and no human representations or approximations of these things. Meillasoux will go on to argue in a number of ways how philosophy can work towards understanding the thing in itself, to see the object and not the set of relations that constitute it for us as subjects. However, he admits that the ‘arche-fossil’ is not a solution to the problem of correlationism, but merely the material, factual evidence that correlationism is a problem. His solution to this will entail a number of manoeuvres that include arguing for a relinquishing of the orthodox notion of causality in favour of a purely contingent and chaotic world of events, as well as championing the ability of mathematics (this he gets from his mentor, Badiou) to access the primary qualities of things in themselves.

Henry Knight, the unfortunate aristocrat that Hardy has hanging from the very Devonian cliffs in which Mary Anning discovered so many important fossils could hardly have imagined that his imagined journey into the past would dramatise exactly what Meillasoux tells us could never happen. Knight is a witness to an ancestral time in which no witness existed. And yet, we know, like Ishmael, who laments his inability to know the whale from its structure, that Knight’s understanding of the ancestral past is entirely imaginary. According to correlationist thought, all of the stories we tell about our past, our environment, our evolutionary history are imaginary, in so far as we are caught within our pitifully limited human frames of knowledge, to which the ‘absolute’ or the being of the world and the universe is inaccessible. However, there sits the fossil; the Plesiosaur, the Ichtyosaur, the ammonite, and the Ottoi Prolifica, all silently and humbly acting as physical monuments to the contradiction of strictly correlationist thinking and to the potential to step outside it even if only in a speculative manner, to see, as Ishmael puts it, ‘precisely what the whale really looks like’.

So the next time you step into the Grant Museum and cast your eyes over the fossils, do not just think about our evolutionary past, or about the incredible forms of life that existed in the distant past, about tentacles and exoskeletons, pterosaurs and sea monsters; think about whether what we can ever know anything about these things at all. Think about the way their existence, for us, is defined only by our ability to construct elaborate and ultimately imaginary stories about them (albeit with some pretty great science!). And finally, think about how a 500 million year old worm gave Immanuel Kant, the most influential philosopher since the Ancient Greeks, something to think about himself.

Reading list:

Thomas Hardy, A Pair of Blue Eyes, ed. by Alan Manford, New Edition (Oxford: OUP, 2005).

Herman Melville, Moby Dick, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, (London ; New York: Continuum, 2009).

Henry Gee, Accidental Species: Misunderstandings of Human Evolution. ([S.l.]: Univ Of Chicago Press, 2015).

For more information on Meillasoux and the ‘speculative realist’ movement in philosophy, The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism is available for free here: http://re-press.org/books/the-speculative-turn-continental-materialism-and-realism/

Close

Close