By Kevin Guyan

By Kevin Guyan

The Student Engagement project was the subject of a paper presented to an audience of museum and gallery professionals, researchers and members of the public at the National Gallery of Ireland Research Day on 6 March 2015.

The day’s theme was Conditions of Display: Research & Practice and preceded the reopening of the gallery in 2016, in which curators will make a number of decisions on rehanging and reimagining the collection. It was therefore an ideal opportunity to share the ongoing link between researchers and public engagement taking place across UCL Museums and the possibilities the Student Engagement project presents for museums and galleries in both the UK and Ireland.

Artists and researchers from a number of UK and Irish universities and art colleges shared their experiences of devising, organising and interpreting exhibitions, as well as the public’s experience of these exhibitions once they go ‘live’.

Sean Rainbird, Director of the NGI, opened the day noting the need to consider the ‘physical experience of humans in space’ when thinking about museums and galleries. Adding that this not only included the arrangement of space and objects but also the management of sound.

Gemma Tipton, known for her commentary on art, architecture and aspects of Irish culture for The Irish Times and regular contributions to TV and radio, raised interesting points about what the exterior of galleries say about the content within. This instantly conjured up the very different entrances to the Grant Museum and Petrie Museum, and whether this shapes people’s interpretations of museum objects prior to their arrival in the museum.

Entrances to the Grant Museum (left) and Petrie Museum (right).

Paul Green, PhD Candidate in the School of Art and Media at the University of Plymouth, shared the ongoing work of Cork’s South Presentation Heritage and the conversion of a convent into a public heritage site. The need to ‘future proof’ the site so that it is ready for unforeseen uses and forms of engagements was insightful, as well as the involvement of design students in devising ways for the public to interact with the objects and space.

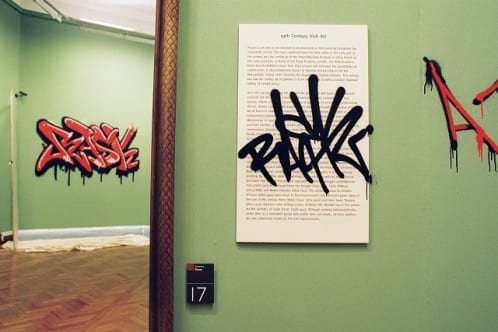

Mirjami Schuppert, PhD Candidate at Ulster University, examined the role of the curator in mediating artistic interventions. She drew a distinction between ‘conventional curating’ and ‘contemporary curating’, which revolves around ‘creative authorship and discursive coproduction’, and expressed the need for those working with archives to give something back in return.

Saidhbhín Gibson, Masters in Fine Art-Sculpture Candidate at the National College of Art and Design, shared her artistic interventions in permanent collections at The Natural History Museum and The Lab, Dublin. She also raised questions over the level of interpretation presented in museums, and the exciting possibilities that emerge when visitors are not given directions on how they should or should not understand an object on display.

Sabina MacMahon, Masters in Museum Studies Candidate at the University of Leicester, discussed her creation of the fictitious South Down Society of Modern Art and exhibition of its work.

Kevin Guyan concluded the day’s papers by sharing the case study of the Student Engagement project and how two-way discussions with visitors helped promote his work as well as reconsider views towards his own research. He argued that curators should build strategies for engagement, like the Student Engagement project, into the planning of exhibitions and hanging of collections from the offset, as it brings a number of benefits for researchers and the public.

The Research Day discussed new ways to share collections.

A panel discussion followed that examined a number of these themes in further depth. One person questioned the expandability of the Student Engagement project to larger, non-university spaces. Though the focus of the project has thus far been UCL’s three campus museums, it seems likely that elements of this project could transfer to differently sized museums not linked to universities. Another person asked whether this style of engagement was dependent on the layout of the museum space? As Student Engagers report differing levels of success in different parts of UCL museums, environment undoubtedly plays a role in people’s willingness to converse.

People clustered afterwards to share their thoughts, both positive and negative, on the Student Engagement project. A few audience members found the idea of a researcher approaching them when contemplating a painting or museum object an unwelcome idea, though admitted that others may enjoy this opportunity to share their opinion on the collection. Others identified the two-way benefits of bringing researchers into the museum or gallery space and were excited by the project’s potential to serve as a training platform for students. Expanding the skillset of PhD students, while also bringing into museums and galleries new methods of public engagement, interested many of those in attendance and it is hoped that elements of the work taking place at UCL appears in other museums and galleries.

Close

Close