Engaging in an Art Museum: Engagement Reflection

By Sarah Savage Hanney, on 17 February 2014

For most visitors to an art museum, there is an unwritten code of conduct that involves silence and whispers when appropriate. As a Researcher in Museums in UCL’s Art Museum, my job is to engage with visitors to discuss the museum and my research. So in a society where museum etiquette is ingrained, how does one get visitors to speak up and engage in a space that is traditionally quiet? When I ask most visitors how they are enjoying the museum and exhibitions, I receive a polite whisper of “It’s good/nice.” In a museum with restricted space availability and therefore few works out on display, it is difficult to engage with a visitor about a collection that is largely stored away.

A significant portion of any museum experience is being able to see, or even touch an object and use one’s senses to interpret the object. So many times I have witnessed visitors to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology touch their own scalp after viewing a mummy’s brunette wig and blonde scalp located in the Main Room. Through visual or audio stimulation, a visitor can make a connection with an object or work whether it’s an emotional response, opinion, or even indifference. It can be such a powerful experience examining a work and feeling a rush of emotion.

Thanks to the great research appointments at the Art Museum, I previously had access to works related to my research on epidemics. Surprisingly, the works that felt most relevant were not the anatomical sketches, but abstract prints from the Slade School of Fine Art. When I do convince visitors to express their opinions of the Art Museum, I always offer to show them a sampling of photocopied works I have deemed relevant to my research.

The study of epidemics involves both examining the experiences of those affected and the spread of the pathogen. By having visitors examine works that evoke emotions of despair and confusion while I explain the Spanish Influenza and Encephalitis Lethargica epidemics, I can more effectively convey individual’s experiences during those epidemics. During the Spanish Influenza pandemic (1918-19), families worldwide felt a variety of emotions as members of their families died quickly and painfully from an influenza outbreak that health professionals could neither control nor determine an origin of contamination. Although Encephalitis Lethargica [EL] affected tens of thousands of people versus millions with Spanish Influenza, EL left the international medical community in a state of utter confusion without a known cause.

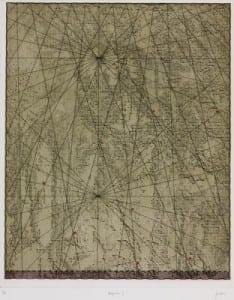

Two of the most popular and powerful works in my art selection are Julia Farrer’s 1971 Navigation I and Alphonse Legros’ 1875 La Mort du Vagabond. Both the works, in the medium of etching and aquatint, are magnificent in person and provoke emotion from the viewer. I interpret Navigation I in a similar way to when I study epidemics. The intersecting lines, red dots and smaller groupings of dots on the work could represent disease spreading through a population with multiple contamination points. La Mort du Vagabond invokes feelings of isolation and helplessness, similar feelings that victims of many epidemics have experienced. By using both of these works in my museum engagements, I can better draw links between my own research and the UCL Art Museum collection.

As I continue with my research and working as a UCL Researcher in Museums, I hope to utilize more objects from the UCL Museum’s Collection in the future. With over 10,000 works in the Art Museum alone, there is so much potential to use public engagement opportunities to connect the public with the collections.

Close

Close