A few weeks ago, the Grant Museum opened a new exhibit, The Museum of Ordinary Animals: boring beasts that changed the world. As a detective of the mundane myself, I am a huge fan. But I’m particularly curious about the ordinary animals we can’t see.

Rather than focusing on a specific artefact label, I answer the title question by visiting two places in the Museum of Ordinary Animals exhibition that help raise questions about how things are organised and labeled in zoology more broadly.

Case notes: Bacteria are everywhere. As I mentioned in my previous post, we have 160 major species of bacteria in our bodies alone, living and working together with our organ systems to do things like digest nutrients. This is also happens with other animals — consider the ordinary cow, eating grass. Scientist Scott F. Gilbert tells us that in reality, cows cannot eat grass. The cow’s genome doesn’t have the right proteins to digest grass. Instead, the cow chews grass and the bacteria living in its cut digest it. In that way, the bacteria ‘make the cow possible’.

The Ordinary Cow, brought to you to by bacteria. Credit: Photo by author

Scientifically speaking, bacteria aren’t actually ‘animals’; they form their own domain of unicellular life. But, as with the cow, bacteria and animals are highly connected. Increasingly, scientists say that the study of bacteria is ‘fundamentally altering our understanding of animal biology’ and theories about the origin and evolution of animals.

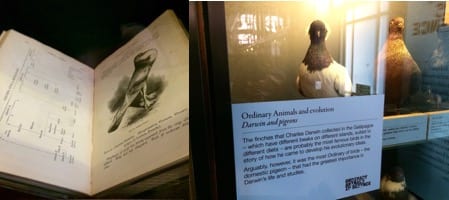

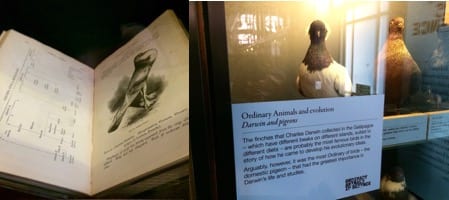

But, before we get into that, let’s go back to Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Darwin studied how different species of animals, like the pigeon, are related to each other, and how mapping their sexual reproduction shows how these species diversify and increase in complexity over time. This gets depicted as a tree, with the ancestors at the trunk and species diversifying over time into branches.

Darwin’s Ordinary Tree of Pigeons. Photos by author

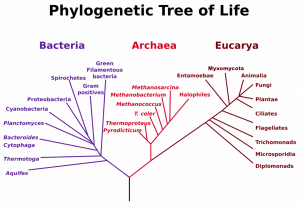

When scientists began to use electron microscopes in the mid-20th century, our ideas about what made up the ‘tree of life’ expanded. We could not only observe plants, animals, and fungi, but also protists (complex small things) and monera (not-so-complex small things). This was called the five kingdom model. Although many people still vaguely recollect this model from school, improved techniques in genetic research starting in the 1970s has transformed our picture of the ‘tree of life’.

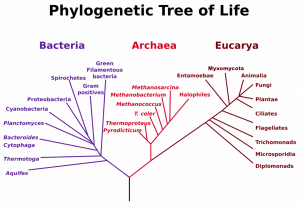

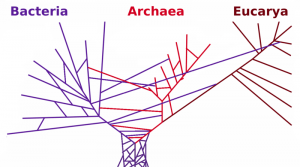

It turns out we had given way too much importance to all the ordinary things we could see, when in fact most of the tree of life is microbes. The newer tree looks like this:

Credit: Wikipedia Commons

Now there are just three overarching domains of life: Bacteria, Eucarya (plants, animals, and fungi are just tiny twigs on this branch), and Archaea (another domain of unicellular life, but we’ll leave those for another day).

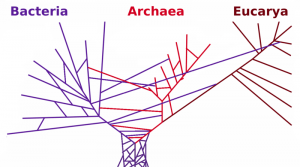

There’s a third transformation of the ‘tree of life’, and this one is my favourite. Since the 1990s, DNA technology and genomics have given us an even greater ability to ‘see’ the diversity of microbial life and how it relates to each other. The newest models of the tree look more like this:

Credit: Wikipedia Commons

This is a lot messier. Why? Unlike the very tiny branches of life (plants and animals) that we focused a lot of attention on early on in the study of evolution, most of life on earth doesn’t reproduce sexually. Instead, most microbes transfer genes ‘horizontally’ (non-sexually) across organisms, rather than ‘down’ a (sexual) genetic line. This creates links between the ‘branches’ of the tree, starting to make it look like….not a tree at all. As scientist Margaret McFall-Ngai puts it: ‘we now know that genetic material from bacteria sometimes ends up in the bodies of beetles, that of fungi in aphids, and that of humans in malaria protozoa. For bacteria, at least, such transfers are not the stuff of science fiction but of everyday evolution’.

Status: Are bacteria Ordinary Animals? We can conclusively say that bacteria are not animals. But, they are extremely ordinary, even if we can’t see them with the naked eye. In truth, they’re way more ordinary than we are.

Notes

As with the previous Label Detective entry, this post was deeply inspired by the book Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, an anthology of essays by zoologists, anthropologists, and other scholars who explore how environmental crisis has highlights the complex and surprising ways that life on earth is tied together. Scott F. Gilbert and Margaret McFall-Ngai, both cited above, contribute chapters.

Close

Close