Summer Lovin’: Why You Need a Pachyderm Paramour

By Sarah M Gibbs, on 23 July 2018

Here’s a special issue of Jungle-politan by our Senior Relationships Correspondent, Sarah Serengeti.

Hey there, Savannah Sisters. I don’t know about you, but when the temperature climbs, the first thing I think about (other than how to avoid crocodile attacks at ever-shrinking watering holes—those cheeky devils!) is summer love. But today’s confusing dating environment often leaves a girl with more questions than answers. Should you go Dutch on that leg of antelope? When is the right time to let him challenge your pack alpha? Is he really that buff, or is he just distending his salivary glands to impress you? Maybe you’re sold on the chimp’s personality. A man who can juggle? What’s not to like? Or perhaps you think the sloth would be your ideal “Netflix-and-Chill” partner. For some ladies, it’s the handyman—the industrious beaver has raised more than a few heart rates—while others live for the bad boy, lone-wolf wolf. But let me tell you from experience, he may hold your paw while you get that full moon tattoo, but he’ll have split long before the ink dries.

That’s why I’m pursuing a new type of man, one with a feature that just can’t be beat: a giant heart. That’s right, girls. This week’s column is dedicated to the African elephant, and let me assure you, the world’s largest land mammal is one of the few tall men whose parts are proportionate. Don’t believe me? Drop by UCL’s Grant Museum of Zoology, where the preserved heart below in on display.

Who doesn’t want a partner whose heart weighs in at a mighty 20 to 30 kilograms? That’s a titanic ticker! It’s ten times as heavy as that purse dog you lost when Nigel the Anaconda got peckish on Fireworks Night. And who better to comfort you in your chihuahua bereavement than someone who will save each of his thirty beats per minute for you? Not to mention that elephant societies are matriarchal. This man will not be threatened by a powerful woman. Career girls, rejoice!

But maybe you’re not convinced. To win you over to Party Pachyderm, Encyclopedia Britannica and I have collected a few more elephant facts that are going to knock your hoof warmers off. Read on for more delightful details about the Stud of the Serengeti.

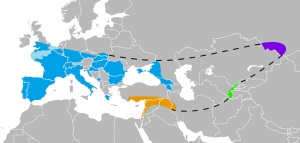

1. Forgot the snacks on the counter? No problem! Your date has a handy dandy trunk, or proboscis, a hybrid upper lip and nose unique to members of Proboscidea, a group that used to count more than 160 species (including mastodons) as members. With a load capacity of 250 kg, your squeeze can grab the crisps, drinks, and even the kitchen table while you recline on the sofa.

2. Need to fell a tree on your property during spring clean-up? Lucky for you, elephants have been used as draft animals in Asia for centuries. Your pachyderm partner can uproot and carry off that endangered heirloom chestnut before you’ve even had time to water the perennials.

3. Tired of waiting for the bathroom? Your elephant love will never keep you idling outside the loo on a busy morning. Mature elephants have only four permanent teeth. Brushing and flossing is complete before you can say “Tusk-Whitening Toothpaste.” Speaking of tusks, talk about some useful enlarged incisor teeth! In addition to protecting the trunk, tusks help elephants dig water holes, lift objects, gather food, and strip bark from trees. And you’ll never feel afraid in that dodgy biker bar with your elephant by your side, as tusks are also super useful for defense.

4. Wondering if he’ll remember your anniversary? Well, ladies, the adage is true: an elephant never forgets. How else would groups manage seasonal migrations to food and water? If that elephant can remember the location of water sources along lengthy migration routes, he’ll never buy tickets for the footie on your nine-month anniversary and then try and fob you off with an Arsenal beer cozy.

So next time you’re tearing your fur out waiting for a text from Mr. “You’re-such-a-pretty-prey-animal-you-make-me-want-to-go-vegan,” take a glance across the watering hole to that bulky bloke consuming his required 100 litres per day. You might just be looking at the elephant love of your life.

Close

Close