By Hannah Wills

A couple of weeks ago, whilst engaging in the Grant Museum, I started talking to some secondary school students on a group visit to the museum. During their visit, the students had been asked to think about a number of questions, one of which was “what is the purpose of this museum?” When asked by some of the students, I started by telling them a little about the history of the museum, why the collection had been assembled, and how visitors and members of UCL use the museum today. As we continued chatting, I started to think about the question in more detail. How did visitors experience the role of museums in the past? How do museums themselves understand their role in today’s world? What could museums be in the future? It was only during our discussion that I realised quite how big this question was, and it is one I have continued to think about since.

What are UCL museums for?

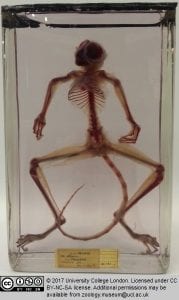

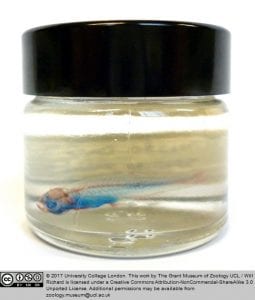

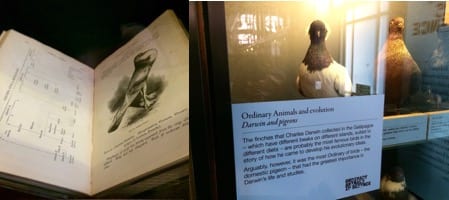

The Grant Museum, in a similar way to both the Petrie and Art Museums, was founded in 1828 as a teaching collection. Named after Robert Grant, the first professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at UCL, the collection was originally assembled in order to teach students. Today, the museum is the last surviving university zoological museum in London, and is still used as a teaching resource, alongside being a public museum. As well as finding classes of biology and zoology students in the museum, you’re also likely to encounter artists, historians and students from a variety of other disciplines, using the museum as a place to get inspiration and to encounter new ideas. Alongside their roles as spaces for teaching and learning, UCL museums are also places for conversation, comedy, film screenings and interactive workshops — a whole host of activities that might not have taken place when these museums were first created. As student engagers, we are part of this process, bringing our own research, from a variety of disciplines not all naturally associated with the content of each of the museums, into the museum space.

What was the role of museums in the past?

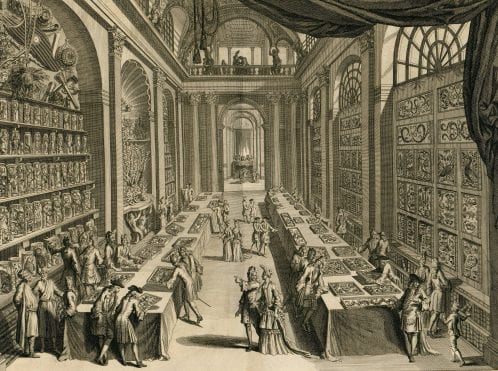

Taking a look at the seventeenth and eighteenth-century roots of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the British Museum in London, it is possible to see how markedly the role and function of the museum has changed over time. These museums were originally only open to elite visitors. The 1697 statues of the Ashmolean Museum required that ‘Every Person’ wishing to see the museum pay ‘Six Pence… for the Space of One Hour’.[i] In its early days, the British Museum was only open to the public on weekdays at restricted times, effectively excluding anyone except the leisured upper classes from attending.[ii]

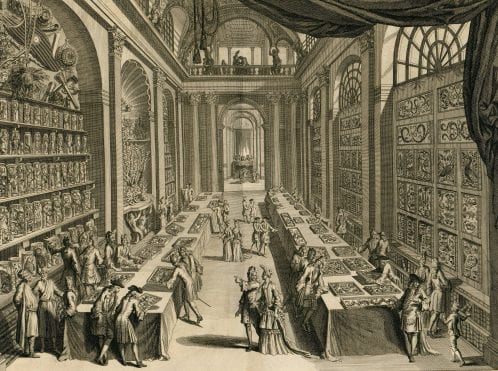

Another feature of these early museums was the ubiquity of the sense of touch within the visitor experience, as revealed in contemporary visitor accounts. The role of these early museums was to serve as a place for learning about objects and the world through sensory experience, something that, although present in museum activities including handling workshops, tactile displays, and projects such as ‘Heritage in Hospitals’, is not typically associated with the modern visitor experience. Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (1683-1784), a distinguished German collector, recorded his visit to Oxford in 1710, and his handling of a range of museum specimens. Of his interactions with a Turkish goat specimen, Uffenbach wrote, ‘it is very large, yellowish-white, with… crinkled hair… as soft as silk’.[iii] As Constance Classen has argued, the early museum experience resembled that of the private ‘house tour’, where the museum keeper, assuming the role of the ‘gracious host’, was expected to offer objects up to be touched, with the elite visitor showing polite and learned interest by handling the proffered objects.[iv]

Aristocratic visitors handle objects and books in a Dutch cabinet of curiosities, Levinus Vincent, Illustration from the book, Wondertooneel der Nature – a Cabinet of Curiosities or Wunderkammern in Holland. c. 1706-1715 (Image credit: Universities of Strasbourg)

How do museums think about their function today?

In understanding how museums think about their role in the present, it can be useful to examine the kind of language museums employ when describing visitor experiences. The British Museum regularly publishes exhibition evaluation reports on its website, detailing visitor attendance, identity, motivation and experience. These reports are fascinating, particularly in the way they classify different visitor types and motivations for visiting a museum. Visitor motivations are broken down into four categories: ‘Spiritual’, ‘Emotional’, ‘Intellectual’ and ‘Social’, with each connected to a different type of museum function.[v]

Those who are driven by spiritual motivations are described as seeing the museum as a Church — a place ‘to escape and recharge, food for the soul’. Those motivated by emotion are understood as searching for ‘Ambience, deep sensory and intellectual experience’, the role of the museum being described as akin to that of a spa. For the intellectually motivated, the museum’s role is conceptualised as that of an archive, a place to develop knowledge and conduct a ‘journey of discovery’. For social visitors, the museum is an attraction, an ‘enjoyable place to spend time’ where facilitates, services and welcoming staff improve the experience. Visitors are by no means homogenous, their unique needs and expectations varying between every visit they make, as the Museum’s surveys point out. Nevertheless, the language of these motivations reveals how museum professionals and evaluation experts envisage the role of the modern museum, a place which serves multiple functions in line with what a visitor might expect to gain from the time they spend there.

What will the museum of the future be like?

In an article published in Frieze magazine a couple of years ago, Sam Thorne, director of Nottingham Contemporary, invited a group of curators to share their visions on the future of museums. Responses ranged from the notion of the museum as a ‘necessary sanctuary for the freedom of ideas’, to more dystopian fears of increased corporate funding and the museum as a ‘business’.[vi] These ways of approaching the role of the museum are by no means exclusive; there are countless other ways that museums have been used, can be used, and may be used in the future. My thinking after the conversation I had in the Grant Museum focussed on my own research and experience with museums, but this is a discussion that can and should be had by everyone — those who work in museums, those who go to museums, and those who might never have visited a museum before.

What do you think a museum is for? Tweet us @ResearchEngager or come and find us in the UCL museums and carry on the discussion!

References:

[i] R. F. Ovenell, The Ashmolean Museum 1683-1894 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), 87.

[ii] Fiona Candlin has written on the class politics of early museums, in “Museums, Modernity and the Class Politics of Touching Objects,” in Touch in Museums: Policy and Practice in Object Handling, ed. Helen Chatterjee, et al. (Oxford: Berg, 2008).

[iii] Zacharias Konrad von Uffenbach, Oxford in 1710: From the Travels of Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach, trans. W. H. Quarrell and W. J. C. Quarrell (Oxford: Blackwell, 1928), 28.

[iv] Constance Classen, “Touch in the Museum,” in The Book of Touch, ed. Constance Classen (Oxford Berg, 2005), 275.

[v] For this post I took a look at ‘More than mummies A summative report of Egypt: faith after the pharaohs at the British Museum May 2016’, Appendix A: Understanding motivations, 27.

[vi] Sam Thorne, “What is the Future of the Museum?” Frieze 175, (2015), accessed online.

Filed under Hannah Wills, Museum Collections, Public Engagement, Research, UCL Collections, Uncategorized

Tags: engagement, Grant Museum, history, museums, public engagement, UCL Researchers in Museums

No Comments »

Close

Close