Although opinions of Neanderthals are rapidly changing within academic research groups, their image as primitive, brutish, and violent, can still be pervasive in wider spread media. This division between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals has deep roots in Europe, exacerbated by the historic tendency to see Anatomically Modern Humans (H. sapiens) as the only behaviourally complex hominin species. The first recognised Neanderthal fossil was discovered in 1856 in the Neander Valley in Germany and rapidly prompted widespread chaos in the scientific community as to where it fitted within the hominin lineage.

Much of this dialogue focused on perceived ‘primitive’ features of Neanderthal anatomy highlighting skeletal differences such as large protruding brow ridges, shorter stature, and barrel-like rib cages (if you visit the Grant Museum a selection of hominin crania are displayed showing some of these differences!). Discussion also focused on disparities in cognitive capacity and behaviour, quickly restricting Neanderthals to a species who favoured hunting over culture, and were more likely to display violence than altruism.

My PhD is based on unravelling aspects of Neanderthal landscape use and migration in the Western English Channel region during the Middle Palaeolithic, a period stretching from around 400 – 40,000 years ago. I am exploring behavioural complexities and reactions to environmental change through Neanderthal material culture, mainly via studying the movement of stone tools. Therefore it isn’t surprising that when I am engaging in the Grant Museum I gravitate towards the Neanderthal cast, which is a replica of the famous skull excavated from the site of La Chapelle-Aux-Saints in France.

Figure 1: La Chapelle-Aux-Saints Neanderthal cast held at the Grant Museum—note the pronounced brow ridge over the eye sockets. Although the mandible and teeth look very different from Anatomically Modern Humans this is a cast taken from the skull of a particularly old individual who had advanced dental problems including gum disease! (Grant Museum, z2020)

Interestingly the most common theme in conversations I have with visitors to the Grant Museum is the shared similarities, rather than differences, between Anatomically Modern Humans and Neanderthals. It seems that what captures our imaginations now are the significance of concepts previously thought of as unique to Homo sapiens that are being gradually recognised in association with Neanderthals. Important advances in dating and DNA analysis have shown that Neanderthals and Anatomically Modern Humans co-existed in Europe for at least 40,000 years, with population groups meeting and interacting at different times. This is seen both in the archaeological record but also in the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome, which indicates that most modern people living outside of Africa inherited around 1-4% of their DNA from Neanderthals. As I mentioned, after the discovery of the first Neanderthal fossils people weren’t too keen on any evidence that threatened to topple the shiny pedestal reserved for Homo sapiens, however these advances in modern science have prompted a greater openness when exploring Neanderthal archaeology.

In order to investigate these aspects of complex behaviour, such as symbolism and art, we consider behaviours preserved in the archaeological record that appear to surpass the functional everyday need for survival. Recent discoveries have suggested that Neanderthals were making jewellery from eagle talons in Croatia and may have had more involvement than previously thought in the complex archaeological assemblages found at sites like Grotte du Renne. However evidence of these behaviours in Neanderthal populations remains rare and although this may relate to the historic viewpoint (it simply hasn’t been looked for…), empirically we just do not see it on the same scale.

Two examples I often refer to when discussing this at the museum are the recent discoveries of potential abstract art at Gorham’s Cave Gibraltar and the Neanderthal structures found underground at Bruniquel Cave. The abstract art (disclaimer: I understand that ‘art’ depends on the definition of the concept itself but that’s for another blog post!) was found at Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar, a well-known Neanderthal occupation site. Often nicknamed ‘the hashtag’ it is a series of overlapping lines that appear to have been made deliberately by repeated cutting motions using a stone tool. The archaeologists who discovered the hashtag suggest that it was created around 40,000 years ago and that, as it was found underlying Neanderthal stone tools, it can definitely be attributed to them. They hail it as an example of Neanderthal abstract art that may even have represented a map, suggesting an elevated level of conceptual understanding. Whatever the marks represent, if they are associated with the Neanderthal occupation of the cave this is a behaviour that has not been observed elsewhere!

Figure 2: An image of the Neanderthal ‘hashtag’ made deliberately with repeatedly with strokes of a stone tool on a raised podium in Gorham’s Cave Gibraltar (Photo: Rodríguez-Vidal et al. 2014)

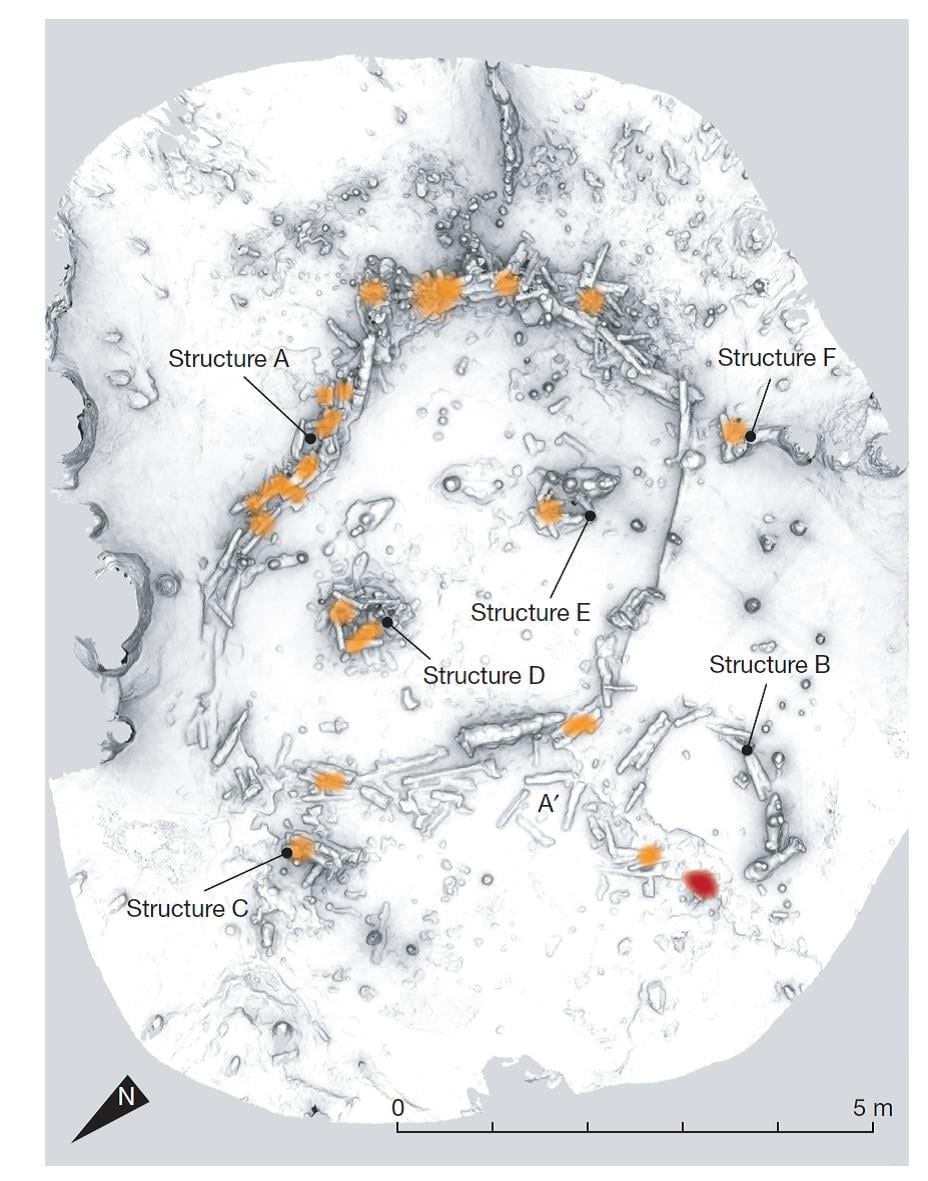

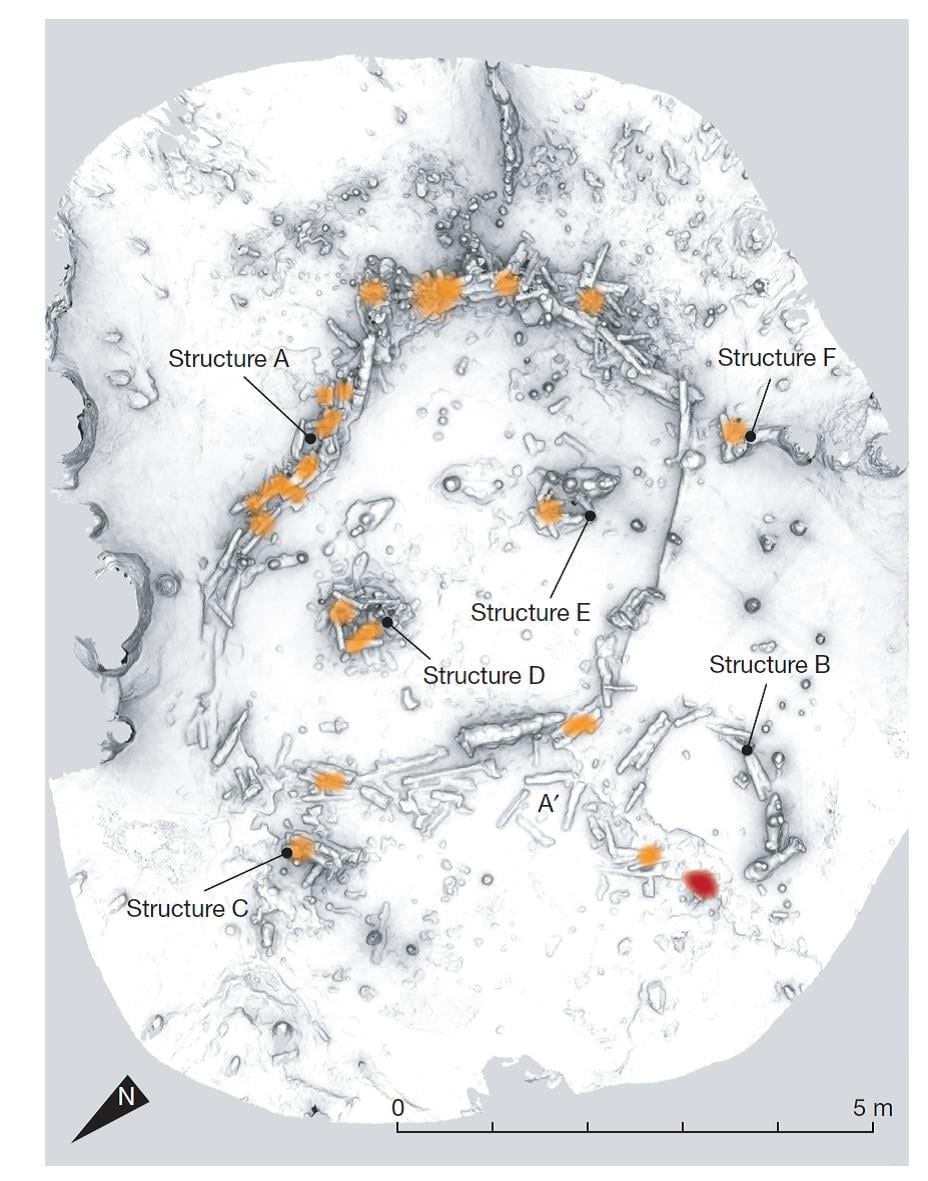

The other example that I mentioned is the site of Bruniquel Cave in southwest France, where unusual underground structures deliberately made from stalagmites have been dated via uranium series to 176,000 years old. This date firmly places the creation of the structures in a time where Neanderthals were the sole occupants of the region. The structures themselves are circular in diameter and are composed of fragmented stalagmites (all of a similar length c.34cm) with evidence of deliberately made fire. The function of these structures is not immediately obvious but as there is a distinct lack of other archaeological material in the cave it is unlikely they were used for domestic purposes. Equally their potential for functioning as shelters is unclear as they are located a whopping 336 metres from the cave entrance in an area that would not have faced the elements.

For me this location deep within the cave presents one of the key implications for Neanderthal behaviour in that no natural light whatsoever would have reached the chamber! This indicates a degree of familiarity with the subterranean world and potentially hints at the symbolic or ritual significance of the cave. Whatever the purpose of the structures, the authors of the study conclude that they represent unique evidence of the use of space, which may reflect the complex social structures of the Neanderthals who built there.

Figure 3: A schematic of the circular structures made with stalagmites deep underground in Bruniquel Cave, the orange colouration shows the areas of deliberate burning (Photo: Jaubert et al. 2016)

The inferences that are made from these Neanderthal finds are carefully considered by both the researchers concerned and the general archaeological community, disseminating the evidence and evaluating what archaeological information can be drawn from it. Overall there is something undeniably privileged to be working in a time where the complexity of Neanderthals is recognised and the potential for art, symbolism and other human characteristics is discussed!

References:

Green, R.E., Krause, J., Briggs, A.W., Maricic, T., Stenzel, U., Kircher, M., Patterson, N., Li, H., Zhai, W., Fritz, M.H.Y. and Hansen, N.F. 2010. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328 (5979), 710-722

Jaubert, J., Verheyden, S., Genty, D., Soulier, M., Cheng, H., Blamart, D., Burlet, C., Camus, H., Delaby, S., Deldicque, D. and Edwards, R.L. 2016. Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France. Nature, 534 (7605), 111-114

Radovčić, D., Sršen, A.O., Radovčić, J. and Frayer, D.W. 2015. Evidence for Neandertal jewelry: modified white-tailed eagle claws at Krapina. PloS one 10 (3), p.e 0119802.

Rodríguez-Vidal, J., d’Errico, F., Pacheco, F.G., Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Jennings, R.P., Queffelec, A., Finlayson, G., Fa, D.A., López, J.M.G. and Carrión, J.S., 2014. A rock engraving made by Neanderthals in Gibraltar. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (37), 13301-13306.

Close

Close