By Qianxi Zhang

This blog was written as a synthesis of a DPU Dialogues in Development event “Designing child-friendly cities: play spaces outside playgrounds”, co-hosted with the UCL’s Critical Childhood Studies Research Group (CCSRG). Qianxi is a one-year visiting researcher at the DPU, working with Dr Andrea Rigon and CatalyticAction on the codesign of child-friendly cities and communities.

Bringing together the designers of cases from China, Lebanon and Italy, the event discussed the challenges and opportunities to make urban neighbourhood child-friendly and play-friendly. Through different marginalised and low-income contexts, the session discussed the importance of unstructured play, play everywhere, intergenerational play, and children’s participation. The session also explored what are the context-specific elements and what learning can be drawn from across the different cases. The event was followed by an open discussion with the discussants Dr Rachel Rosen from the Institute of Education, UCL, Dr Yat Ming Loo from the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, and Dr Helen Woolley from the University of Sheffield. The Bartlett Development Planning Unit and UCL’s Critical Childhood Studies Research Group (CCSRG) co-hosted the event.

Case 1: Designing Play Spaces for Children in Migrant Workers’ Communities in China

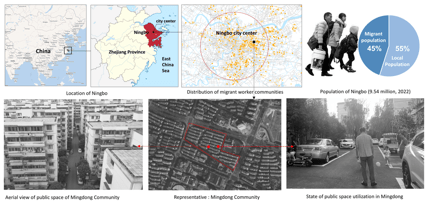

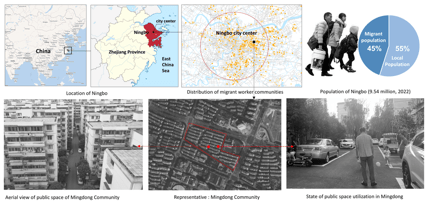

As the first speaker from NingboTech University and University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Qianxi Zhang introduced a child-friendly school-to-home street intervention she designed, which is located in a representative migrant worker’s community named Mingdong community in Ningbo City. The child-friendly street in the community holds great social-ecological value for mitigating the challenges of play insufficiency and social isolation among children in migrant workers’ communities in China.

Mingdong community was built in 1996 and has 120,000 square meters of construction areas with 56 residential buildings, 170 households, and 5500 residents, of which the migrant population is around 3000. It has a well-developed external urban infrastructure with a lot of public amenities. By contrast, its internal public space is extremely full of tension. It’s a typical gated community characterized by a grid-like road network. Large parks or public spaces are scarce within the community, and residents’ outdoor activities are restricted to the streets which mainly serve as internal transportation and parking services. In this ecological environment, children’s outdoor play and independent mobility are also severely inadequate, and sidewalks become their primary daily activity areas. Additionally, 56% of residents are from outside Zhejiang Province, such as Anhui and Henan provinces, etc. Most of them face language and cultural barriers with limited social support networks.

Figure: The social-ecological environment of the Mingdong community

The Mingdong community was designated in 2019 as the host site for the Young Planning Professionals (YPPs) workshop, which was arranged as part of a collaboration among international organizations (ISOCARP, UNICEF) and local authorities (the Urban Planning Society of China and the Ningbo Urban Planning Bureau). The primary objective of this workshop was to provide international young planners with actual community planning while engaging with children, to achieve the goal of ‘Child-friendly Urban Planning’. This was the first time that the concept of a Child-friendly City has been recognized by local community managers and residents. In 2020, the Mingdong community received specialized funding from the Ningbo Municipal Government for the purpose of renovating the overall infrastructure and public space environment of old communities. In light of this development, community managers extended an invitation to a local university (NingboTech University) design team and a regional design company (Ningbo Urban Planning and Design Institute) to collaborate in exploring methods of incorporating child-friendly concepts within the overall regeneration plan. Subsequently, the decision-making team designated a street linking the community and the school to create the most beautiful and playful child-friendly walking route.

Figure: Development and actor-network dynamic of the intervention

Before regeneration, the site size was very limited and the buildings along it lacked attractive interfaces and engaging functions. It was devoid of any street furniture or ancillary amenities and was consistently encroached upon by motor vehicles. The design strategy was dividing the layout planning of the existing sidewalk space into four major functional zones: frontage zone, clear path, street furniture zone, and buffer zone. In conjunction with site-specific characteristics, physical elements such as play and learning spaces, green landscape areas, street furniture and seating were adaptively integrated. Moreover, a traffic calm intervention was incorporated. Additionally, the community volunteer culture and school football culture were identified as opportunities to shape the public spirit of the community and were manifested through spatial elements design. For instance, various community cultural materials such as community slogans, story photos, exemplary figures, and important events, were posted on the interfaces of the rotatable boxes in the arch door, allowing children and residents to learn about community culture and governance stories in a fun and interactive way.

Figure: Streetscape before and after intervention

The renovated sidewalk exhibited significantly higher usage rates than its previously neglected state. The various affordance of play, learning, nature, and other amenities provided by the sidewalk were used by children as anticipated by the designer. Additionally, children displayed creative use of these amenities. In addition, nearby elderly residents have also begun to move tables and chairs to this area to play cards. This space has gradually become a shared space for all residents, thereby building new forms of common

Figure: Diverse usage behaviors of children and other residents in the renewed street

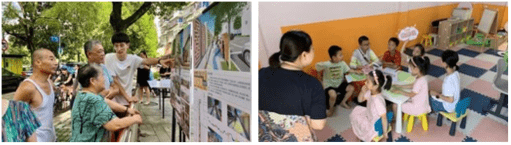

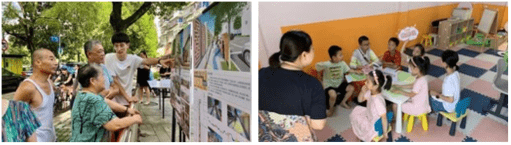

The design team organized a community open day to showcase the regeneration design schemes for the entire community in the public space. The design intentions were presented to the residents in a more intuitive and vivid form, such as environment drawings, renderings, and models. Additionally, representative children participated in the discussion of the design plans for the child-friendly sidewalk renovation project.

Figure: Children and resident’s participation in the design scheme discussion

Reflections: play-based street intervention can bring a lot of positive effects on migrant workers’ community in China, such as (1) creating more play spaces and opportunities for children’s physical activity and recreation, and improving the overall health and wellness of children, (2) provide a platform for children and caregivers to interact with their neighbors, build relationships and form a sense of community, and (3) create opportunities for children to engage in social and cultural exchange with other members of the community, fostering mutual understanding and respect.

However, challenges remain. The construction of play spaces is very dependent on government policy support and special funding subsidies. But government funding can only guarantee necessary projects, such as playgrounds, while play spaces outside playgrounds are not a mandatory indicator in Chinese communities, resulting in similar projects only being attached to other project packages, the landing of this project is therefore highly contingent. Without the call of professionals and the involvement of the private sector, it is difficult to scale up similar projects at present in China. Secondly, more evidence and interdisciplinary knowledge are needed to understand how children interact with the urban environment and their preferences, so as support the evidence-based design of play spaces outside playgrounds. This knowledge needs more children’s lens and voices.

Case 2: Designing child-friendly cities: play outside playgrounds in Lebanon

The second speaker is Riccardo Conti, co-founder and Executive Director at CatalyticAction which is a charity that uses design and architecture to empower vulnerable children, young people, and their communities. Children’s participation in every step of the process from initialization to design, but also the construction. The methods of participation include mapping in the neighborhood, one-to-one interviews to discuss ideas and identify solutions, and also model making and mural painting in the construction. CatalyticAction generates an impact mostly on children’s well-being, but also improves the local capacity and the local economy. In particular, as it prioritizes the use of local materials and skills, it also has an impact on social cohesion and inclusion as they work with different groups inside the community.

It’s really important to speak about play outside playgrounds, especially in a context like Lebanon, where playgrounds in public spaces are really scarce. There is a common observation that whether it’s a street or a parking lot, or basically anywhere where there are no cars, kids playing could be found.

Four play space projects in different urban sites were introduced, including one on public steps, one on a waterfront, one on a street, and one on a residual space.

Play space project on public stairs:

The project on public steps involves the rehabilitation of a public stair that was damaged in the 4th explosion in 2020. The design objectives include improving the physical environment, enhancing accessibility, and restoring social activities. Several design elements will be incorporated, including a slide, handrails with wooden spheres painted by local residents, and speaking pipes. In addition, the project will involve organizing activities to help residents reclaim the stair and its social value. Due to budget constraints, the design incorporates multiple functions into a single element, and some conventional design rules were negotiated with the municipality. Finally, the project will incorporate a unique participation method using Minecraft, a video game, to co-design with children.

Play space project along the waterfront.

The play space project along the waterfront is challenging due to the lack of basic facilities and a limited budget. The design objectives and strategies aim to provide caregivers with facilities that are easily accessible from their homes for daily use. The project is divided into three separate locations along the waterfront, each with a different focus – some encourage physical play, while others are designed for people to enjoy the natural beauty of the waterfront. The design incorporates items suitable for all age groups. Local researchers will be engaged as a participation method. The success of the project will be indicated by the site being populated by people of different ages and nationalities after the regeneration.

Play space project on street

The project is located on a street between a public hospital and a public park, which has the problem of excessive space allocated to cars. The design strategy is to increase the pedestrian space by reducing the space for cars, but this involves negotiation with the municipality. Design elements include permanent floor games, bicycle rocks that are popular with children for playing and going under, funky benches or climbable elements, safe crossings, and seating arrangements. To ensure long-term maintenance, pigments are included directly in the cement mix. The project also incorporated a unique participation method, as children were involved in marking the location.

Play space project in residual space

The project in the residual space involves designing a space that is larger than a sidewalk but not big enough to be a public park or playground. The design strategy involves transforming the space into a larger sidewalk. The design element includes a colorful bench. After construction, children were observed using the space as predicted – running, sitting, and jumping over the bench. Unexpectedly, some people also came to skateboard in the area. Children used the division of the colors on the bench to play marbles, as well as the slope of the bench to slide. The participation method used for this project involved design consultation.

Case 3: San Siro child-friendly neighborhood in Italy: a design perspective

The third speaker Gianfranco Orsenigo from Politecnico di Milano introduced a Grow up well project in San Siro, which is a social housing neighborhood in Milano. In his research, he investigates how architectural design can equip itself to become a key stage in the process of transformation of marginal territories. He is a member of Mapping San Siro, an action-research project in the public housing neighborhood of San Siro in Mila

The San Siro neighborhood is located in the North-west part of the city and is one of the largest public housing projects built between the 1930s and 1950s, adhering to the modern movement. The neighborhood consists of around 6,000 housing units and is inhabited by approximately 11,000 people, with 77% being owned and managed by Aler Milano, the Regional Housing Agency. Despite its size and population, the neighborhood has been suffering from institutional neglect and mismanagement, resulting in a sense of abandonment and decay of the built environment, leading to its classification as an “internal periphery.” However, the area is surrounded by areas of significant urban development, including City Life and the San Siro Stadium, and is well-connected to the city as a whole via the M5 underground and stadium.

The neighborhood is super diverse, with residents from over 85 different nationalities. More than 48% of the population has foreign origins, and there is internal diversity in terms of culture, religion, social status, dwelling conditions, and migratory backgrounds. However, there is polarization between the younger (18% of whom are foreigners) and the elderly population (mostly Italians, comprising 36% of the population). Unfortunately, the Roma population is excluded from this diversity. The largest foreign communities in the neighborhood are from Egypt (37.2%), Morocco (10.4%), the Philippines (9.5%), and Peru (6.1%), according to Anagrafe Comunale 2012.

The Mapping San Siro project and the West Road Project are two action-research initiatives that aim to promote positive change in neglected urban areas of Milan. Mapping San Siro began in 2013 with a workshop that focused on countering the negative perception of the San Siro neighborhood through research and pilot projects, including the Trentametriquadri space, SoHoLab Project, and Off Campus San Siro. The project involved reopening spaces, building trust-based relationships with the local community, and creating a multisource observatory to combine different forms of knowledge. It was carried out in collaboration with Aler Milano and Regione Lombardia. The West Road Project, which won the Polisocial Award in 2017, is part of the social engagement and responsibility program at the Politecnico di Milano. It employs spatial analysis and co-design methods to improve neglected spaces and promote the development of local cycling connections, using multidisciplinary approaches and building prototypes of transition through experiments to establish local relationships based on trust. Together, these two groups focus on (co)design, networking, and project development as tools to directly support local actors and communities.

The Pillar of Public Spaces and common spaces focuses on improving the quality and dignity of the public and common spaces in San Siro, using them as a tool to understand the neighborhood and build relationships based on trust with locals. This helps create a constantly updated image of the area and formulate more precise questions for future change. The group employs two main approaches: first, the use of prototypes of transition, which are small realizations that demonstrate the potential for change and act as drivers for new experiences. These prototypes also help evaluate project hypotheses and activate imaginaries for future transformations, engaging both locals and public institutions in triggering a future of change. Second, the group has developed a vision for the future called “Growing up well in San Siro.” This vision focuses on the young population, who are a fragile group in the neighborhood due to their status as newcomers and second-generation immigrants. School dropout rates are high among these young people, who represent 36 different nationalities and 95% of the student population. This leads to issues of school segregation. However, the group sees the young people as an opportunity to reimagine the neighborhood as an infrastructure for growing well, with public spaces as support for new paths of protagonism, expression, and creativity.

In San Siro, the younger population is considered fragile due to their status as almost newcomers and second generations of immigrants. The school dropout rate is a significant issue in this neighborhood, with 95% of students being foreign and representing 36 different nationalities, leading to a problem of scholar segregation. However, this challenge also presents an opportunity to reimagine the neighborhood as an infrastructure for growing well. By providing space and support for new paths of protagonism, expression, and creativity, the community can create a brighter future for the younger generation.

The Patto via Gigante project is a prototype for transition and aims to create an accessible connection for pedestrians and cyclists between social places and schools in Milan. The project involved rethinking a portion of the pavement on Via Gigante that was improperly used as a car park and storage for bulky goods. The new public space was designed and constructed between March 2019 and October 2020, using public collaboration agreements, a new instrument that the municipality of Milan recently implemented. The project was carried out in cooperation with 11 local association partnerships Overall, the project serves as a model for how public collaboration agreements can be used to transform urban spaces and improve accessibility for pedestrians and cyclists.

The design elements of the project included a new graphic along the pavement, a wooden platform with flower boxes, new furniture donated by Vestre AS, and two bicycle racks. The new graphic along the pavement served as a visual cue to the transformation of the area, while the wooden platform with flower boxes provided an inviting and aesthetically pleasing space for people to gather and socialize. The new furniture donated by Vestre AS, including the only public table in the neighborhood, created a functional space for people to sit and enjoy the area. Additionally, the two bicycle racks were an important addition for encouraging sustainable transportation and reducing the use of cars.

The building day played a critical role in involving and engaging locals, particularly through the curiosity of children. This initial contact served as a foundation for future engagement when the project was completed. The project also involved students from the faculty, incorporating educational art and practical education. Observations have shown that the transformed space has the potential to become an actively engaged tool in daily life. This engagement extends beyond children and also includes parents and relatives, creating relationships that can lead to the development of co-design services with local associations. For instance, children from the public space could participate in cultural events or assist with homework, among other possibilities. This prototype serves as a tool for building cooperative networks and triggering new interventions.

The project team has developed five additional prototypes to improve public spaces in Milan. The first prototype is the green living lab, which rethinks the pavement of Via Abbiati by transforming a street corner into a green space. The second prototype is the Trabucco Gigante, which is a deck platform in a courtyard that can be used for cultural events, daily activities, and free play. The third prototype, Cortile Cadorna, aims to redesign the school backyard with more natural elements to support the school’s activities and the parents’ initiatives. The fourth prototype, Campo Gioco Aretusa, is a new playground located in a traffic island and sponsored by Recordati spa. This playground is an excellent example of collaboration between public, private, and local community organizations. It provides an opportunity for students to use the neighborhood as a field of experience and encourages them to be more active in their community.

Insights from discussants

- Rachel Rosen, Institute of Education, UCL

Richel’s sociological perspective on childhood and space design highlights the social construction of childhood and the role of space in transforming social relations. By designing space for childhood, it can address the challenge of generational segregation and promote intergenerational connections. The importance of spaces in between is emphasized, as children prefer to play in spaces that are not solely designated for play. It is meaningful to design for openness and new imaginaries. Reclaiming rights in urban public spaces are also highlighted, as low-resource initiatives through co-design, coordination, and co-building can create a sense of reclaiming commons. Co-designing play spaces outside of playgrounds can build new forms of common. The questions raised are how designers and researchers can challenge and disrupt generational segregation and address power relations, such as unequal access to resources.

- Yat Ming Loo, University of Nottingham Ningbo China

Yat Ming focuses on the contextual differences in play space design in different cultures. One important factor is cultural differences, such as intergenerational nurturing and the intercultural environment caused by internal migration in China. These cultural factors can affect the understanding of play and childhood, and therefore impact the design of play spaces. Another aspect to consider is the power relation between top-down government funds and bottom-up NGO support in China. The role of memory also plays a significant role in creating childhood experiences. All of these factors should be taken into account when designing play spaces in different cultural contexts.

- Helen Woolley, University of Sheffield

Helen, an expert in landscape architecture, shares several perspectives on play spaces and childhood: Firstly, she believes that play is an integral part of childhood, and children will find ways to play everywhere. Even elements within streets can provide opportunities for play. Secondly, she observes that children often use spaces that were not initially designed for play, calling them “children’s constructed and found spaces”. Thirdly, she suggests that small interventions can be impactful in building a bigger matrix of a child-friendly city. Fourthly, she proposes that a successful play space is one that is well-used by people of all age groups, and that improving the physical environment can enhance social cohesion. Finally, she raises the question of how to effectively evaluate and demonstrate to politicians and funders the positive impact of play space interventions on quality of life.

Filed under Diversity, social complexity & planned intervention

Tags: Beirut, children, china, community, DPU Diallogues in Development, DPU Event, event, Italy, Lebanon, Milan, Ningbo, participation, play-space, public space, space, well-being

No Comments »

Close

Close