Crowdsourcing inputs for future impact evaluation? Pilot participatory mapping for liveability and health baselines of a transport-centred project in Cali, Colombia

By ucfudro, on 2 April 2019

This blog is part of the health in urban development blog series – the full series can be found at the bottom of this post.

___________

Urban transport and mobility are critical instruments for development, health and sustainability. Transport is one of the most data-, land- and resources-intensive sectors in urban public policy, consuming often more than a third of public budgets in Global south cities and being explicitly linked with many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. However, conventional transport planning lacks sufficient tools, policies and methods that make explicit the links between transport, liveable and sustainable cities, and health. This blog showcases a participatory methodology for drawing a baseline and developing future impact assessment on liveability and the social determinants of health in transport-driven large-scale urban interventions. The blog argues for the use of health-informed methods using our research experience in Cali – Colombia’s third largest city – in the implementation of web-based participatory mapping tools for a project in the implementation phase.

The centrality of transport to urban development trajectories

Transport is a very effective instrument for urban policy definition and delivery. As showcased by the rapidly increasing number of kms of Bus Rapid Transit (BRTs), cable-cars, cycling lanes and many such other projects built in recent years throughout Latin America, transport has claimed a central role in current urban development trajectories. For instance, out of the 170 cities that have implemented Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems globally, 55 (32%) are in Latin America, with 1,816 km of BRT networks built regionally (BRTDATA.ORG, 2018). Investments in mass public transport infrastructure have opened the door for urban transformations driven by transport developments via promotion of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), reclaiming of public spaces, development of non-motorised infrastructure, and other transport-land-use integration strategies. Strategies such as the above have enabled sustainability and climate-change adaptation agendas to redefine some of the relationships between built environment and transport infrastructure across the region (1; 2). There is also larger awareness in the research and policy spheres about the health implications of transport, from a preventive medicine and physical activity perspective, to access to healthcare, environmental exposures and road safety (e.g. 3; 4; 5).

The Caliveable project

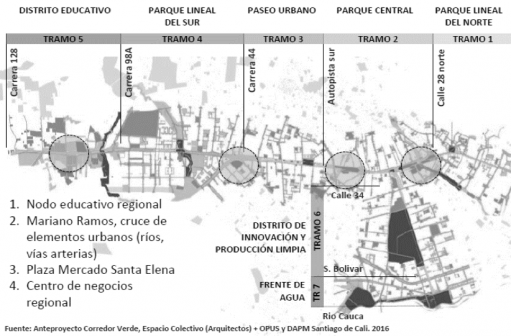

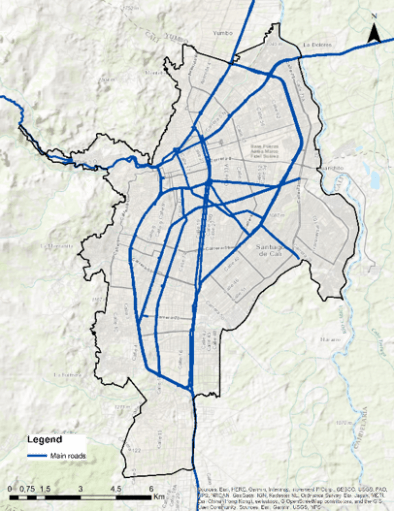

The Caliveable project (www.caliveable.com) is a research initiative led by Dr Daniel Oviedo at the DPU and funded by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The project involves a multi-disciplinary team of UK-based and Colombian researchers seeking to develop frameworks and methods for baseline studies of liveability and the social determinants of health of nascent transport-centred urban projects. The project argues that by building on rigorous and tested frameworks such as liveability, which are cross-cutting to both the built environment and health, it is possible to construct tailored baselines for the design, monitoring and evaluation of the effects of transport-centred interventions on the social determinants of health. The project studies Cali’s Corredor Verde (CV) as the empirical context for the development and implementation of the study. The CV is a large-scale infrastructure and public space investment programme aimed at enhancing social, economic and regional integration with a regional train at the centre of urban interventions traversing the city from north to south.

The Corredor Verde project has a modern public transport system intending to serve as regional link with emerging poles of population and economic growth near Cali (e.g. Yumbo, Palmira). The corridor also intends to become an environmental anchor and axis for supporting urban biodiversity, linking interconnected biodiversity points and support structures – such as waste and recycling plans, nurseries and educational trails. The transport dimension of the project aims to promote active travel and urban transformations based on the notions and principles of TOD, which align with the overall objective of re-unifying the eastern area of Cali with the rest of the city. However, there is no evidence on how this is consistent with the implementation of measures that promote determinants of health and liveability neither on the guidelines or the project’s masterplan. Moreover, given the socio-spatial distribution of the population, the investment rises questions regarding its distributive effects. Will the citizens from both sides of the corridor be benefited equally? Could the CV create an increase in land value and consequently ignite processes of gentrification and expulsion of low-income residents?

Harnessing the links between transport, liveability and health

We aim to examine liveability in seven domains – employment, food housing, public space, transport, walkability and social infrastructure – linked with health and wellbeing outcomes (6). Two challenges emerge when approaching a project such as the Corredor Verde from a liveability perspective: the first is lack of purpose-built data for comprehensive analysis of the different dimensions of the concept, the second is lack of resources for collecting a sufficient sample that can serve in later stages for impact evaluation. The Caliveable project addresses these challenges using web-based geo-questionnaires designed for participatory mapping. We optimised resources available to deploy targeted field data collection campaigns in areas with lower income and access to technology and neighbourhoods with high levels of illiteracy and other restrictions for self-reporting. Using Maptionnaire (www.maptionnaire.com) the team has designed a comprehensive 15-minute questionnaire dubbed The Calidoscopio, that allows building indicators based on numerical scales, Likert, multiple choice question, multiple choice grid and draw buttons. Drawbuttons are a feature of the approach of participatory GIS as it enables respondents to map out different features of their behaviour and their urban environment.

The Maptionnaire platform enables the construction of geographical-based features, making it possible to crowdsource mapping for different purposes. For example, a respondent is asked to draw the area of the neighbourhood they perceive as more polluted and then evaluate how they perceive how this contributes/affects their quality of life. The graphical result allows both the interviewee and the researcher to work with a superposition of georeferenced and self-completed information layers. The platform also allows mapping routes and points in the city, which are relevant for transport-specific analysis such as accessibility and walkability. The superposition of layers of analysis through easy visualisation is one of the key advantages of the web-based tool for participatory GIS.

Initial findings from the deployment of the liveability questionnaire in Maptionnaire have produced comprehensive information about behaviours, preferences, needs and perceptions, not often captured by traditional data collection methods applied in transport studies. The tool enabled the research team, even from the pilot stage, to add a spatial dimension to variables explicitly linked with the social determinants of health, informing location, distribution and characteristics of the built environment from an urban health perspective. This will inform not only planning and development of the Corredor Verde and other relevant transport infrastructure projects in Cali, as well as leaving a replicable methodology for monitoring and evaluation. The Caliveable project seeks to establish alliances with government authorities and researchers for the appropriation of the tool and scaling-up of the methodology for future health monitoring and impact assessments of the Corredor Verde.

Learning from the experience: transport equity and participatory mapping

Experiences with the use of alternative methods for data collection have been introduced in the DPU’s curriculum for years. Such practice has continued in the context of our Transport Equity and Urban Mobility module of the masters in Urban Development Planning course. Students have received training in the Maptionnaire tool and have had the chance of designing and deploying a small-sample test survey in the London Bloomsbury area. Students from across the DPU and the Bartlett have used participatory GIS questionnaires to address issues such as night-time mobilities, liveability and well-being related to transport, transport and security, and walkability. The experience with the use of innovative methods and technological tools for data collection have served for collective reflections about the role of data in leading to more inclusive and sustainable urban transport planning and the need for grounding innovative methods in rigorous conceptual frameworks and context-specific considerations as those covered during the module. The exercise also informed reflections related to research ethics, data management and privacy and the challenges of development research in the digital age.

References

- Paget-Seekins, L., & Tironi, M. (2016). The publicness of public transport: The changing nature of public transport in Latin American cities. Transport Policy, 49, 176-183.

- Vergel-Tovar, C. E., & Rodriguez, D. A. (2018). The ridership performance of the built environment for BRT systems: Evidence from Latin America. Journal of Transport Geography.

- Sarmiento, O. L., del Castillo, A. D., Triana, C. A., Acevedo, M. J., Gonzalez, S. A., & Pratt, M. (2017). Reclaiming the streets for people: Insights from Ciclovías Recreativas in Latin America. Preventive medicine, 103, S34-S40.

- Salvo, D., Reis, R. S., Sarmiento, O. L., & Pratt, M. (2014). Overcoming the challenges of conducting physical activity and built environment research in Latin America: IPEN Latin America. Preventive medicine, 69, S86-S92.

- Becerra, J. M., Reis, R. S., Frank, L. D., Ramirez-Marrero, F. A., Welle, B., Arriaga Cordero, E., … & Dill, J. (2013). Transport and health: a look at three Latin American cities. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29, 654-666.

- Badland, H., Whitzman, C., Lowe, M., Davern, M., Aye, L., Butterworth, I., … & Giles-Corti, B. (2014). Urban liveability: emerging lessons from Australia for exploring the potential for indicators to measure the social determinants of health. Social science & medicine, 111, 64-73.

Health in urban development blog series

How and in what ways can local-level risk information about health and disasters influence city government practices and policies?

By Cassidy A Johnson

Treat, contain, repeat: key links between water supply, sanitation and urban health

By Pascale Hofmann

Health in secondary urban centres: Insights from Karonga, Malawi

By Donald Brown

Gaza: Cage Politics, Violence and Health

By Haim Yacobi

Close

Close