‘Look what I was like when I moved to the ‘villa’’, Sara told me, sending me her photo via WhatsApp. We have been talking about her housing story for weeks now. According to her grandma, the picture was taken in their first home in Villa 21-24, in the south of Buenos Aires.

A decade later, with a partner and a kid, the girl in the photo would move to a bigger house near the Riachuelo’s riverbanks. The location of this second home will change her story. In 2008, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled that, due to pollution, all families living within 35 meters of the river should be relocated. Paradoxically, from then on, being registered next to the Riachuelo became a golden ticket to access social housing.

I met Sara in 2018 when I joined the Housing Institute of Buenos Aires to coordinate the second phase of the relocation program. Over time, our bureaucratic exchanges turned into long afternoons of conversations and mates. Sara and her husband told me multiple stories about the community and helped me understand some slum dynamics. Now, I once again rely on them to re-discover Buenos Aires’ housing policy.

Image 1: Sara (left) and her brother Walter (right). Source: provided by the interviewee (date unknown).

***

Since their emergence, the villas (squatter settlements) have been subject to eclectic government policies. A product of internal migration in the late ’30s, they were first seen as a temporary phenomenon that enabled the country’s industrialization. Later, the successive military governments considered that these ‘illegal occupations’ entailed a social threat. During the ’70s, families were expelled to their ‘places of origin’ or simply dumped on vacant land outside the city’s limits. Eradication policies and forced disappearances explain the drastic decrease in slum population: from 213,823 in 1976 to 34,064 in 1980 (Dadamia, 2019). ‘Living in Buenos Aires is not for everyone but for those who deserve it’, synthesized the Housing Minister of that time (in Oszlak, 1991).

Fortunately, Sara’s story begins at a brighter time. She was born in 1985, during the first years of democratic rule. Committed to prosecuting human rights violations, the new government definitely abandoned the eradication paradigm towards the long-settled villas. In Buenos Aires, the ‘Slum Settlement Program’ (Act 39.753/84) recognized the right of slum dwellers to remain in their place. Later, the right to housing would be guaranteed in the 1994’s National Constitution.

However, none of the successive housing and land regularization programs achieved widespread implementation. As part of the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s, the ‘Plan Arraigo’ (Law 23,967/1991) promoted the sale of all public land deemed ‘unnecessary’ and the transfer of property titles to their occupants. But even this policy designed to guarantee tenure security was limited and suspended shortly after. In Buenos Aires, only a few received housing through some short-lived ‘street opening’ programs and even less acquired their land titles (Di Virgilio, 2015).

Our story begins with a State that, while recognizing its responsibility in guaranteeing housing rights, systematically fails to fulfill it. Describing the literal waiting process inside welfare offices, Javier Auyero argues that the urban poor are forced to become ‘patients of the state’. Because even this ‘downsized, decentralized, and “hollowed out” state’ can still provide them ‘limited but vital welfare benefits’ (Auyero, 2012, p. 5). But as others have said before, this waiting process is always active. Individually or collectively, the urban poor deploy different strategies to dispute or negotiate with the State (Fainstein, 2020), and they learn which are the ‘correct ways to ask’ (Olejarczyk, 2017). They embrace ‘survivability’, because while the existence of the villas has ceased to be threatened, their residents still live a life ‘in a constant state of instability’ (Lees and Robinson, 2021, p. 594). As we shall see, Sara’s story is one about survival.

***

Sara arrived at Villa 21-24 when she was still a kid. Established on public land, near industrial areas and railways, the settlement had reached 12,000 families in the ‘70s before the eradication policy reduced the number in half. Sara’s father, Ángel, had endured the military rule in the villa but eventually managed to move to his father’s house 30km away from Buenos Aires. However, with three kids and a wife who did not adapt to the new town, he decided to return.

They bought a house there in the late ’80s, taking advantage of the new democratic approach. The certainty that they will never be evicted by the State is strongly felt throughout Sara’s narration. ‘We were never afraid of being evicted. Here in the villa, (…) I never saw bulldozers go by.’

Of those early years, Sara’s memories are somewhat blurred. Her parents separated shortly after their return. Sara stayed in the house with her father and her younger sister Yanina. There were times when they also lived with Walter and Pablo, her mother’s children, but dates are not clear. What is certain is that the house was small, made of corrugated metal and wood, and had two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bath.

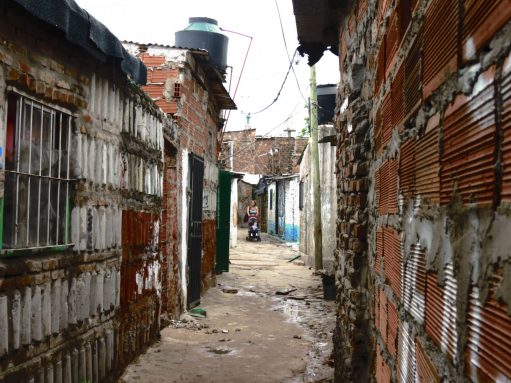

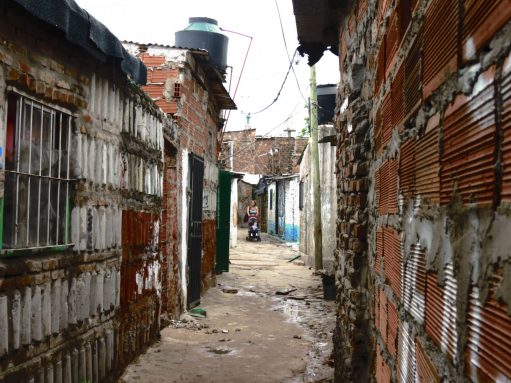

Like most houses, theirs had an informal power line, but it did not have an independent water connection. They had to go to the community faucet in the ‘middle corridor’ (pasillo) to get water. She recalls that many people went to look for water there. Maybe it was the only faucet for the entire neighbourhood, but she is not sure. What we know is that all the infrastructure was developed by the community. A true example of ‘social production of the habitat’. Even today, official water and electricity lines are found only on the villa’s perimeter and on the two avenues that cross it. They only reach what the public services providers persevere in calling the ‘formal city’.

Although the house was small, they did not reform it until Sara got pregnant at the age of 14. To give them some independence, her father decided to fix a small ‘brick room’ on the side of the house. She moved there with her partner, Leonardo, when their son Ezequiel was born.

Image 4: Villa 21-24 in 2002. Source: Google Earth

***

‘ – Did you ever think about leaving?

– One always dreams of leaving (…). But the opportunity didn’t come along. (…) Leonardo was 16 and didn’t have a permanent job. He did informal gigs, waste-picking with a cart. (…) We lived day to day’.

Sara could not afford to move alone, even less outside the villa, where landlords usually request tenants to guarantee the lease with another proprietor’s deed. Buying a house through the market was even less of an option, as access to long-term credit and loans is restricted to those with formal income, not to say, with substantial previous savings in US dollars. She was also skeptical of state programs. Her grandmother had tried to access a home through the cooperative in charge of implementing the ‘land regularization program’. But despite having paid several installments, the cooperative leader ended up arbitrarily assigning the land plots in exchange for cash. Dozens of families were scammed, and the State did nothing. They were on their own.

However, even with their daily struggles, they managed to save some money. Eventually, in the early 2000s, they had the opportunity to move to a larger house within the villa, which they jointly bought with Sara’s father. This was a ‘brick house’, with water and electricity connections, a living room, a bathroom and a large patio. It also had three bedrooms, which could accommodate what were now three distinct families: Sara’s, Yanina’s, and Angel’s.

Interestingly, in Sara’s account, there are no references to the Riachuelo river, even when the new house is located a few meters from it. However, in 2004, on the opposite riverbank, a group of neighbors filed a lawsuit denouncing the environmental damage they had suffered due to the Riachuelo’s high pollution levels. In 2008, the Supreme Court of Justice would order the National State, the Province and the City of Buenos Aires to clean up the river’s basin and improve the resident’s livelihoods. Two years later, the Court would further rule that all the people residing 35 meters from the Riachuelo had to be relocated. With this decision, 1534 families living in Villa 21-24 were granted the right to social housing.

Image 5: Villa 21-24 in 2010. In purple, the relocation area. Source: Google Earth (2010)

***

In 2011 the Housing Institute conducted a census to identify which families would be affected by the relocation. By this time, the residents had managed to organize themselves into a Body of Delegates elected by each ‘block’. They had also requested the presence of the Public Defense and other judicial institutions to monitor the government’s procedures. But Sara never actively participated in those spaces.

“We didn’t believe it (…). The 2011 census was like any other census, once again. They didn’t tell us that one day that census would help us have an apartment… or a different life… like open the tap and getting hot water’.

However, with time, the 2011 census certificate became the most precious document, the one that could guarantee, essentially, an improvement of the living conditions, the ‘hot water’. Eventually, even houses were sold ‘with the former owner’s census certificate’, as a strategy to transfer with it the ‘relocation right’.

Image 6: Villa 21-24 immediately after the relocation. Source: City Housing Institute (2014).

***

The first relocation began in 2013. The Housing Institute was willing to start from the western end of the villa, where the houses’ demolition would allow the extension of the coastal road, but the Delegates refused. San Blas was the newest neighborhood, ‘squattered’ in 2006. Although they held the same relocation rights, community criteria valued ‘seniority’, that in this case also meant longer exposure to pollution. Backed by the Public Defense lawyers, they convinced the government to relocate the families suffering critical health issues first. This meant starting from the middle, closer to Sara’s house.

In a process denounced for its limited community participation, between 2013 and 2015, 165 families would be moved to the ‘Padre Mugica’ complex, 11 km away from their original homes. However, those years are blurred in Sara’s memories. Around this time, Leonardo’s older brother is murdered by one of his longtime neighbours. When arrested, his relatives come out to threaten Sara and Leonardo’s family. So in an act of explicit survival, leaving all their belongings behind, they abandon their house. For the next few years, they will become tenants in Zavaleta, a settlement located next to the Villa 21-24.

***

From my reconstruction of the story, I know that Sara’s father moved to ‘Padre Mugica’ in 2015. According to Sara, by this time, Ángel was suffering from health issues, and their house, which before stood out for its spaciousness and comparative beauty, had deteriorated sharply. Because of the ‘imminent’ relocation, ‘new construction’ was banned by the government, and even emergency improvements were seen as a waste of resources. Angel’s situation did not go unnoticed by ‘el Choro’ and ‘la Pety’, the Delegates of Sara’s block. Mostly because of their claim, he was prioritized in the relocation, even though his house was not scheduled for demolition at this stage.

Sara remembers accompanying her father to some government meetings before the relocation. There she was able to tell her story to a social worker: she had been forced to leave her home, and although she was no longer living by the Riachuelo, she needed to secure her relocation right. The following years, she would tell her tale multiple times to different government employees, including the Public Defense lawyers. The Housing Institute finally gave her a ‘signed compromise’ where they guaranteed her an apartment in the ‘Padre Mugica’ Complex, which was still under construction.

***

During the five years she lived in Zavaleta, Sara had to move three times. She suffered the instability of the vast majority of tenants, aggravated by the informality of contracts. Fortunately, the new monthly rental costs were not a problem. By that time, Leonardo had a formal job that provided a stable income. At some point, Sara applied for a ‘housing subsidy’ from the local government. But she did that to reinforce her housing rights. ‘I asked for the subsidy because I was told that (…) if I left [the Housing Institute] alone and didn’t bother them (…) they would forget about me’.

However, this ‘active wait’ was long. Sara was meant to be relocated to the ‘Padre Mugica’ complex, but the government decided to cancel its construction when the building’s quality proved to be deficient. Learning from this failed experience, the Delegates mobilized to get the new houses built next to the villa. But even when they managed to get a bill sanctioned (Law Nº 5172/14), the construction was extremely slow. Four years passed by without progress.

Image 8: Sara’s housing story. Source: Google Earth (2020).

***

At the beginning of 2018, the Housing Institute carried out a new survey to update the 2011 census, although no new ‘housing rights’ were granted. This time, the relocation would begin from the San Blas neighborhood, but some ‘urgent’ cases would be considered.

‘And that’s when my aunt Elsa told me, ‘Sari, go find out because they already called me twice’. When I went, the guy told me that I wasn’t on the list. So I brought him the census certificate and the signed compromise’.

Unlike most families, whose fight had been to relocate closest to their original homes, Sara needed to move far from her former neighbors. ‘San Blas’ neighborhood was the best option for her. In that process, she surrendered yet again to State inspection, of which, this time, I was a part. She registered with her family in a new census. She told her story for the umpteenth time to the new government’s team. She participated in ten relocation workshops to meet her new neighbors. She voted to elect their ‘building’ leader. She actively argued to be assigned an apartment next to her son, Ezequiel, who by this time had his own child and therefore required an independent home.

I was there when, in January 2019, Sara signed the 30-year loan and her apartment’s deed. A week later, she finally moved into her new home.

***

Sara’s story is one about survival. In a country where only the wealthy can access housing through the market, Sara learned how to patiently deal with the State. She faced first the State as an absence: one that at least would not violently evict her from the house she self-procured but that provided little else. Later, the State became the inevitable intermediary, the one from whom to demand access to safe, secure and proper housing. A right granted to her as a way of exception, of which so few were beneficiaries. And in that process, she became a ‘patient of the state’.

But Sara’s waiting was also active. She toured countless public offices, reminding the ever-changing state employees of her story. Being registered on the 2011 census became her best narrative. But, as the 900 families still living by the Riachuelo prove, this was not enough.

Image 9: San Blas’s housing complex. Source: City Housing Institute (2020).

Excused behind budgetary constraints, the State demands the urban poor to be worthy of the public benefits. In a reinvented ‘meritocratic’ logic, it forces them to build their stories around ‘topics of misfortune’. Rights are granted according to a proven critical ‘urgency’. With a kinder face, the democratic State creates new categories to measure who ‘deserves’ and who ‘does not deserve’ to be benefited from the right to housing.

But Sara understood how to tell her story. She learned how to play the game. She strategically negotiated with the State and won. She showed she ‘deserved the city’.

***

Since 2016, the new local government has promoted upgrading projects in four of the city’s largest villas. The programs contemplated the construction of social housing for those affected by the construction of new roads and public spaces. Unfortunately, scarce resources were granted to incremental in-situ improvements. The delays in infrastructure works (water, sanitation and drainage) mean that, in the short term, proper housing is only guaranteed for those few relocated to the ‘new homes’. This time, different rules determine who is worthy of State benefits.

But no housing story ends with the relocation. Because living in the ‘formal’ city and paying the mortgage, services and public expenses create other challenges for the urban poor. And once the ‘urgency’ is resolved, the State tends to disappear.

Sara’s survivability (like many others) will undoubtedly be displayed thousands of times more.

References

Auyero, J. (2012) Patients of the State. The Politics of Waiting in Argentina. Duke University Press. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Dadamia, R. (2019) ‘Asentamientos precarios en la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires’, Población de Buenos Aires., pp. 20–33.

Di Virgilio, M.M. (2015) ‘Urbanizaciones de origen informal en Buenos Aires. Lógicas de producción de suelo urbano y acceso a la vivienda’, Estudios demográficos y urbanos, 30(3), pp. 651–690.

Fainstein, C. (2020) ‘Problemas del mientras tanto: espera y justicia en la causa “Mendoza”.’, Avá, (36), pp. 165–193.

Lees, L. and Robinson, B. (2021) ‘Beverley’s Story: Survivability on one of London’s newest gentrification frontiers’, City, 25(5–6), pp. 590–613. doi:10.1080/13604813.2021.1987702.

Najman, M. (2017) ‘El nacimiento de un nuevo barrio: El caso del Conjunto Urbano Padre Mugica en la ciudad de Buenos Aires y sus impactos sobre las estructuras de oportunidades de sus habitantes’, Territorios, (37), p. 123. doi:10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/territorios/a.4978.

Olejarczyk, R. (2017) ‘El tiempo de la (in)definición en las políticas de vivienda: De “tópicos del infortunio” a “saberes expertos” [The time of (in)definition in housing policies: from “clichés of misfortune” to “expert knowledge” ]’, Trabajo Social Hoy, 82(Tercer Trimestre), pp. 89–110. doi:10.12960/TSH.2017.0017.

Oszlak, O. (1991) Merecer la ciudad. Los pobres y el derecho al espacio urbano. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

This housing story is part of a mini-series revealing the complex ways in which personal and political aspects of shelter provision interweave over time, and impact on multiple aspects of people’s lives. Space for strategic choice is nearly always available to some degree, but the parameters of that choice can be dramatically restricted or enhanced by context. The wide range of experience presented in this collection shines a light on the wealth of knowledge and insights about housing that our students regularly bring to the DPU’s learning processes.

Close

Close