It’s hardly arguable that one of the most prevalent human activities is picking sides. From ethnic conflicts down to people’s taste in music, the world finds itself divided – by nationalism, classism, other-isms or simply a difference of opinion. And amid the Brexit aftershocks and cries over racial violence in the States, amid the broken trust and broken spirits flooding our news channels, where does the term “universal” stand? How can we, in these circumstances, imagine a unified vision to take care of each other?

Although the built environment has a way of reinforcing social divisions, whether through gender-specific bathrooms or communities ghettoised by gentrification, it can also host spaces that inspire solidary over status, and spaces that actively embrace the most excluded people of our societies. Today, pockets of planners and architects work to promote a less socially divided world, and some of them are doing it through universal design.

Universal design, defined

Often presumed as design for people with disabilities, universal design actually embraces a much broader definition. It is “the design and composition of an environment so that it can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by all people regardless of their age, size, ability or disability.”[1] In other words, it tries to befriend as many as possible – selfish in a selfless way. It assumes all people have disabilities to some extent;[2] just as we gain abilities with age, we also lose abilities – whatever “normal” is on this spectrum will always be trend-related and misguided.

The term was coined by Ronald L. Mace, an American architect who at age nine contracted polio, became a wheelchair user, and in his twenties had to be carried up and down the stairs at university.[3] It was perhaps forecasted, then, that he would help institute the first accessibility building codes in the United States in 1973, which went on to influence national policies including the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[4] During this period he also founded what is now the Centre for Universal Design at New Carolina University.

His legacy not only etched a space of dialogue for disability discrimination but also raised the question of what constitutes social norms to a new height. “Unfortunately,” Mace said in a speech, “designers in our society also mistakenly assume that everyone fits this definition of ‘normal.’ This just is not the case.”[5]

Young Ronald L. Mace (source); Mace later in life as an architect (source)

Mace’s work evolved from recognising people’s differences to harmonising them – from disability design (focused on the inclusion of one group) to universal design (embracing all individuals’ differences). The strength in universal design is that it simply acknowledges human diversity. With no technical guidelines, it serves as a new reference point for practitioners, informed by anthropological understanding – sort of like a social justice challenge.

No rules attached

Tar-Saeng Studio, an offshoot of the collective Openspace with whom I’m working in Bangkok as part of the DPU/ACHR/CAN Young Professionals Programme, is helping to grow universal design into Thai society. Using participatory approaches channelled through the comforts of informality, they create spaces attentive to the often overlooked needs of elderly people and people with disabilities, who live on low-incomes or in poverty. The studio is run by a small group of community architects who are in their mid-twenties to early thirties. They represent a new generation of practitioners building urban resilience through inclusive design—both in product and process.

When I chatted with Tar-Saeng Studio founder Ploy Kasama Yamtree about universal design, I found it interesting that their work is largely dependent on the country’s institutional gaps. “In Thailand, universal design is still linked to regulations, like the correct ratio for a ramp or handrail,” Ploy said, “But when you go into people’s bamboo houses, you see it’s not possible to have the 1:12 ratio because people just don’t have that type of space.”

Conveniently, building codes go unenforced in most remote or slum areas of Thailand, giving Ploy’s team creative freedom to shape genuinely usable spaces for those who need them. “We go and figure out what we can do without following the rules,” she explained, “We are more interested in adaptive design.”

There’s a very human approach to all this. Building codes unquestionably play a role in keeping our societies safe, but like with anything institutionalised they can be restrictive to the ever-changing contexts. Tar-Saeng Studio chooses to carry out their work—safely and strategically—whether it adheres to the legal systems or not, for they do it to solve problems, not to abide by the confines that sustain problems.

And in the process they are making a point – “When we design and don’t follow building codes because it’s impossible to, it’s a statement we’re putting out there that these building codes need to change,” Ploy said.

Tar-Saeng Studio works with vulnerable populations to provide living environments suited to their needs. (Photo: Openspace)

Designing for Thai society

Before Tar-Saeng Studio was established, Openspace worked in some of Thailand’s poorest communities and noticed this widespread but untrodden issue. In 2013, about 7.3 million people in Thailand lived below the poverty line, and another 6.7 million were at risk of falling below it.[6] For these people, access to safe shelter is already a struggle. Thailand is also the world’s third most rapidly aging country with more than 10 percent of people over 64 years old,[7] and it’s projected that by 2040 this number will jump to 25 percent—that’s one in every four people.[8] And of the near 2 million people with disabilities,[9] almost 40 percent are above the age of 64.[10] Adapting for an aging society in Thailand with increasing cases of disabilities is just smart planning, yet no one was doing it.

The first time Openspace actively applied universal design was in 2011, or as people here call it “flood year” – referring to the floods that caused 884 deaths and an estimated loss of 45.7 billion USD.[11] In a riverside community in Pathum Thani province, elderly people felt uncatered for in the local amenities. The goal was to create a space in which they can socialise, exercise, and spend time in. More importantly, a space where they can connect with each other and lead healthier lives, and where the inherent vulnerabilities from unwanted isolation can dissipate over time.

Openspace worked side by side with the local people, like a true partnership. Using low-cost materials like discarded bamboo and motorcycle tyres from nearby shops, they made an area consisting of benches at varying heights, a hanging garden, and an exercise station—it was modest, useful, beautiful. The benches aimed to connect the elderly with the children; the hanging garden had attached platforms for stretching legs; the exercise station held removable weights made of stones stored in bamboo. Everything served a purpose in bettering older people’s lives. Equally as valuable were the skills gained and relationships reinforced within the community, and perhaps a proud sense of ownership to something they collectively brought to life.

A few months later came the floods during which the structures were destroyed. Ploy heard that after the water subsided, the community rebuilt the space. “It was really nice to hear,” she said.

Community members weaving a bench seat with recycled tyres for a socialising/exercising space for elderly people; the space being exhibited; the hanging garden on site of the community (Photos: Tar-Saeng Studio)

Eager to pursue universal design with greater commitment, Openspace partnered with the Institute of Health Promotion for People with Disability, a government entity, on a four-month project involving seventeen people with disabilities living in underprivileged conditions. Most of them were in rural housing unfit for accessibility building codes, and couldn’t afford the “standard” equipment for their needs. This is the reality; affordability should be integral to accessibility but disability-focused design can be expensive, leaving out those who are poor.

Openspace visited the seventeen people across two provinces. Case by case, they studied the clients’ health and living conditions then came up with low-cost design solutions, published in an illustrative book titled Differently-Abled Architecture. It includes people with cerebral palsy, paraplegia, hemiplegia, deafness, blindness, and mobility difficulties from diabetes.

In one case, they created an “at-home playground” for an eight-year-old boy with cerebral palsy that allowed him to stretch different parts of his body and aid the development of his muscles and joints. It was constructed from bamboo, rubber tyres and concrete. Another project was a “DIY horizontal toilet” built into wooden floors, and beneath it sat a plastic bucket connected to pipes, a hose, and a water tap. It was for a client who couldn’t sit up but was perfectly capable of moving around in his own ways; he just needed an environment suited to his methods of self-reliance.

These projects underscored the basis of universal design – understanding the concept of “normal” as shifting with the users, all of whom differ.

Ploy measuring the hand of an eight-year-old client with cerebral palsy; drawings of the “at-home playground” shown in Differently-Abled Architecture. (Photos: Openspace)

What Ploy grasped at the end of the four months was the dismally isolated nature of these cases. These were just seventeen of 2 million people with disabilities in Thailand, who happened to be among the poorest populations, divorced from public assistance. There was no space in which they can support each other, no platform on which they can be heard, and no signs of progress towards their inclusivity.

“I decided that in our next projects we wouldn’t do it the same way,” Ploy said, “Instead we will combine many cases. A process of building together, and taking care of each other, would be better.”

“Lit Eyes”

At this point, in 2013, Ploy set up Tar-Saeng Studio, a private entity detached from government organisations—detached from politics, a precarious area of discussion in Thailand—aimed to mainstream universal design into Thai society. The word tar saeng means “lit eyes” in Thai and “community” or “villages” in Laos, chosen to give familiarity to local people (whereas Openspace, a mishmash of English design jargon, means little to many). Through Tar-Saeng Studio, Ploy would advocate for the inclusion of vulnerable populations to built environment practices.

But she also acknowledges it won’t be easy. The concept of universal design is still alien to most, and when it does ring a bell to some it’s often perceived as an extra luxury, covered by extra costs, sacrificed from the “real” necessities. Trying to convince poorer communities to embrace universal design principles has been tough. Many say they simply don’t see the point; meanwhile Ploy would watch them struggle to move around their homes.

She realised it will take a lot more awareness raising before implementation can go full force, and decided to keep the message simple, which was, “Look, there are no rules. It’s about knowing your own resources and adapting to your environment.”

Since then, Tar-Saeng Studio has undertaken a series of projects ranging from low-cost furniture making to hospital design. Their outputs are always based on inclusive design principles, and their processes on participatory empowerment. They’ve also published and distributed books to institutions and the wider public, and held training workshops in small communities. It is Ploy’s hope for Tar-Saeng to become a social enterprise one day, with income from private sector clients subsidising projects for poor communities. “It’s very important to connect with people doing similar things from different sectors,” she mentioned, “You can’t really do this alone.”

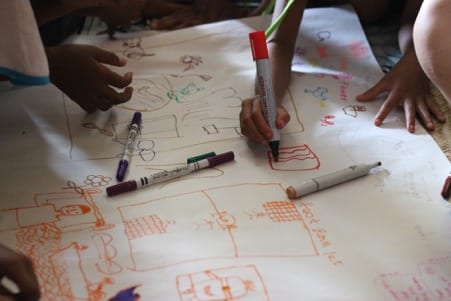

Tar-Saeng Studio holding a community workshop in Ching Rai on universal design for public space. (Photo: Tar-Saeng Studio)

What this means for urban resilience

The floods of 2011 brought great devastation across Thailand. People lost their homes, they felt desperate, they wanted answers. This triggered a well-needed public dialogue on urban resilience and climate change adaptation; like a newcomer experiencing culture shock, Thailand had struggled to cope with these new waves of events and adapt to a new language through which to understand them. So this was a good step.

A city’s urban resilience is characterised by its social and physical capacity to take on different types of pressures, endure through them, and recover from them.[12] Whether hit by an earthquake or economic recession, things like governance, ecosystem balance, physical infrastructure, social services, and community support networks, all determine how a city bounces back. Conversations around urban resilience in Thailand, however, remain primarily on physical infrastructure, while social capacity—people’s knowledge, mental and physical health, and resourcefulness during a time of crisis—have remained more or less a faded backdrop.

Ploy’s decision to focus on universal design, she told me, has everything to do with building urban resilience in Thailand. People are aging, losing abilities, living in poverty, and some need particular types of assistance. The fluctuating climate is also adding to these stresses. She said, “What we’re doing is planning for the future, for the environment that’s always changing.” Tar-Saeng Studio is proving that building adaptive environments through participatory approaches can increase social capacity by minimising vulnerabilities and strengthening communities. Their next goal is to demonstrate that these grassroots activities can be scaled-up to the regional and national levels.

It’s as if Mace predicted the volatile state of the world today and decided to send a note to the future. In a 1998 speech he said, “I’m not sure it’s possible to create anything that’s universally usable…We use that term because it’s the most descriptive of what the goal is, [which is] something people can live with and afford.”[13] What seemed like a vague statement then has become significant in today’s social practice. I’ve noticed that Ploy rarely speaks about disability, elderly, or po-poor focused designs as independent from each other, but instead she talks about making environments inclusive to everyone. Now I understand how she’s running with Mace’s words. But it’s not that these things—disability, elderly, pro-poor focused designs—always go together either. I guess universal design is like a head-to-toe winter outfit that you modify according to the weather that day. You just need to check the forecast to make the best decision.

As Mace wrapped up his last speech, at a New York conference in 1998, he said, “We are all learning from each other in a wonderful way and need to continue what we have started here—communication and the exchange of ideas and experience.” And eighteen years later, reading his words were a small group of young architects in a traditional Thai house, lying on the floor, scribbling away, planning for the future.

References:

[1] Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, 2012. What is Universal Design. [online] Available at: <http://universaldesign.ie/What-is-Universal-Design>

[2] Mace, R. 1998, ‘A Perspective on Universal Design’, speech, New York, 19 June. Available at: <https://www.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_us/usronmacespeech.htm>

[3] Saxon, W., 1998. Ronald L. Mace, 58, Designer Of Buildings Accessible to All. [online] 12 July. Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/13/us/ronald-l-mace-58-designer-of-buildings-accessible-to-all.html?_r=0>

[4] Center for Universal Design (2008) About the Center: Ronald L. Mace. [online] Available at: <https://www.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_us/usronmace.htm>

[5] Mace, R. 1998, ‘A Perspective on Universal Design’, speech, New York, 19 June. Available at: <https://www.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_us/usronmacespeech.htm>

[6] The World Bank, 2016. Thailand: Overview. [online] Washington: The World Bank Group. Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/overview>

[7] HelpAge International, 2014. Aging population in Thailand. [online] Available at: <http://ageingasia.org/ageing-population-thailand1/>

[8] The World Bank, 2016. Aging in Thailand – Addressing unmet health needs of the elderly. [online] 8 April. Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2016/04/08/aging-in-thailand—addressing-unmet-health-needs-of-the-elderly-poor>

[9] International Labour Organization, 2009. Inclusion of People with Disabilities in Thailand [pdf fact sheet] International Labour Organization.

[10] Thongkuay, S., 2016. People with Disabilities – Thailand Country Profile [draft report 2016].

[11] Impact Forecasting LLC, 2012. 2011 Thailand Floods Event Recap Report Impact Forecasting. Chicago: Aon Corporation, p.3.

[12] 100 Resilient Cities, 2016. What is Urban Resilience? [online] Available at: <http://100resilientcities.org/resilience>

[13] Mace, R. 1998, ‘A Perspective on Universal Design’, speech, New York, 19 June. Available at: <https://www.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_us/usronmacespeech.htm>

Cindy Huang is an alumna of MSc UDP and a participant of the DPU/ACHR/CAN Young Professionals Programme, currently working on community-driven development projects with Openspace and the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights network in Thailand.

Filed under Diversity, social complexity & planned intervention, Urban Transformations

Tags: ACHR, Bangkok, CAN, climate change adaptation, community, design, disability, ecosystem balance, empowerment, governance, Openspace, participatory methodologies, participatory research, physical infrastructure, social capacity, Social diversity, social services, Thailand, Universal design, urban resilience

2 Comments »

Close

Close