I have sung and praised the sun disc, I have joined the baboons

By Gemma Angel, on 15 April 2013

by Suzanne Harvey

by Suzanne Harvey

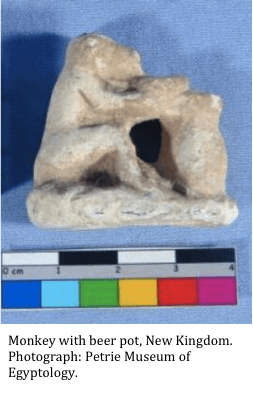

What links the evolution of language to the collection of baboon figurines at the Petrie Museum of Egyptology? I have previously speculated on the reasons why Ancient Egyptians might create figures of baboons performing acrobatics, playing the harp and even drinking beer. After months of sporadic research and conversations with museum visitors on the subject, I have finally chosen a favourite theory (without a hint of bias) that just happens to link directly to my own research on baboon communication.

This post was inspired by an essay entitled Some Remarks on the Mysterious Language of the Baboons, [1] which mentions this quote from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Chapter 100:

This post was inspired by an essay entitled Some Remarks on the Mysterious Language of the Baboons, [1] which mentions this quote from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Chapter 100:

I have sung and praised the sun disc, I have joined the baboons.

The reason that Egyptians considered baboons to be sacred is actually quite straightforward. When baboons wake in the morning, like many primates (humans included), they tend to stretch and produce vocalisations. To some, the pose baboons adopt while stretching – sometimes raising their front legs in the air – resembles worship. As they stretch more often at sunrise, this action together with their ‘chattering’ noises when moving from sleeping sites, was interpreted as singing and dancing to praise the Sun-god, Ra. [2]

This only explains the role of language in making baboons sacred. Of several Gods to whom they are sacred, the deity who links baboons unequivocally with language is Thoth. Thoth is often depicted as a baboon scribe who not only spoke and wrote, but who actually gave the gift of language to the Egyptians, rather than simply understanding it. [3]

This only explains the role of language in making baboons sacred. Of several Gods to whom they are sacred, the deity who links baboons unequivocally with language is Thoth. Thoth is often depicted as a baboon scribe who not only spoke and wrote, but who actually gave the gift of language to the Egyptians, rather than simply understanding it. [3]

The voice of the baboon is the voice of God

This title might seem a somewhat unusual interpretation of the famous vox populi, vox Dei maxim, but it is in fact the Ancient Egyptian variation on this theme. Their belief was that whoever understood the language of the baboons had access to religious knowledge that was usually hidden. This is very good news indeed for modern primatologists – though I’ve yet to decipher any religious revelations while analysing baboon vocalisations! I can however dispute the Greek author Aelianus’s assertion that baboon language is “utterly incomprehensible to ordinary human beings”. [4]

Thoth’s significance in language and wisdom suggests that my earlier supposition – that baboons playing harps and drinking beer was not linked to religion due to the absence of sober, worshipful poses – was in fact erroneous. It seems that Egyptians were motivated to experiment with baboons, trying to train them to perform feats such as playing the harp, to reveal the link to Thoth hidden within them.

Thoth’s significance in language and wisdom suggests that my earlier supposition – that baboons playing harps and drinking beer was not linked to religion due to the absence of sober, worshipful poses – was in fact erroneous. It seems that Egyptians were motivated to experiment with baboons, trying to train them to perform feats such as playing the harp, to reveal the link to Thoth hidden within them.

A range of baboon statuettes are currently on display as part of the Foreign Bodies exhibition in UCL’s North Cloisters. They represent a unique interpretation of other species that are nevertheless similar to our own, and a fascinating insight into how a distant culture defined themselves in relation to other primates – believing themselves to be inferior to baboons in terms of both holiness and wisdom. Ancient Egyptians recognised the human-like intelligence, ability to communicate and dexterity of baboons that we are equally fascinated by today, albeit from an evolutionary science perspective, rather than a religious sensibility. The quest to discover the inner Thoth continues…

References:

[1] H. Te Velde: ‘Some Remarks on the Mysterious Language of the Baboons,‘ in Kamstra, J. H., Milde, H. & Wagtendonk, K. (eds). Funerary Symbols and Religion. (1988), J.H. Kok: Kampen.

[2] G. Pinch: Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. (2004), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Close

Close