Consanguinity and Incest in Ancient Egypt

By Alexandra Bridarolli, on 16 August 2018

My curiosity was piqued during one of my turns at the Petrie Museum. Facing all these artefacts, traces of dynasties of pharaohs, I was suddenly reminded of the stories of incest and marriages between brother and sister which were common in ancient Egypt among the ruling class. More recently, the topic was brought up again by another visitor. I was then told about Akhenaton’s androgynous appearance that could have been a result of the incestuous practices of the time. This practice seems to be a common thing and these stories made me immediately think of the Greek and Roman gods and their intricate family-love relationships. With this thought came then one question: why would pharaohs marry their sister, mother and other relatives? To act as living gods? To preserve the purity of their blood?

Fig. 1: Limestone statuette of Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Princess (Tell el Amarna). [Petrie museum, UC004]

Many others questions followed: If incest was accepted in ancient Egypt among the ruling class, was it tolerated by the whole population? What makes it unacceptable in Western countries today? Health? Morality? Are marriages among siblings and/or first cousins still allowed nowadays in some countries? And what are actually the risks of incestuous relations?

From ancient Egypt to the Habsburg family in Europe, throughout history cases of consanguinity — mainly among members of the ruling classes — are numerous. It is surprising that the practice continued for as long as it has when religious and civil laws started to forbid it and when the risks associated to this practice started to be known; from the 5th century BCE, Roman civil law already forbade couples from marrying if they were within four degrees of consanguinity (Bouchard 2010). From the half of the 9th century CE, the church even raised this limit to the seventh degree of consanguinity and the method of calculating degrees was also changed. More recently, modern philosophers and thinkers argued that the prohibition against incest was a universal phenomenon, the so-called incest taboo . But this theory seems contestable in view of the Egyptian case.

So why is it that incest was accepted and practised in ancient Egypt and more recently among members of the royal family such as the Habsburg (16th-18th century)? And how did science shed the lights on family relationships, incestuous practices and the diseases resulting from them?

Let’s first take the case of the 18th dynasty, the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt.

Incest in Ancient Egypt: the case of the 18th Dynasty

There is an abundance of evidence showing that marriages or sexual relations between members of the “nuclear family“ (i.e. parents, children) were common among royalty or special classes of priests since they were the representatives of divine on Earth. They were often privileged to do what was forbidden to members of the ordinary family. During the Ptolemaic period (305 to 30 BCE) the practice was even used by King Ptolemy II as “a major theme of propaganda, stressing the nature of the couple, which could not be bound by ordinary rules of humanity” (Chauveau, M.).

Fig. 2: Alabaster sunken relief depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and daughter Meritaten. Early Aten cartouches on king’s arm and chest. From Amarna, Egypt. 18th Dynasty. [Petrie Museum, UC401]

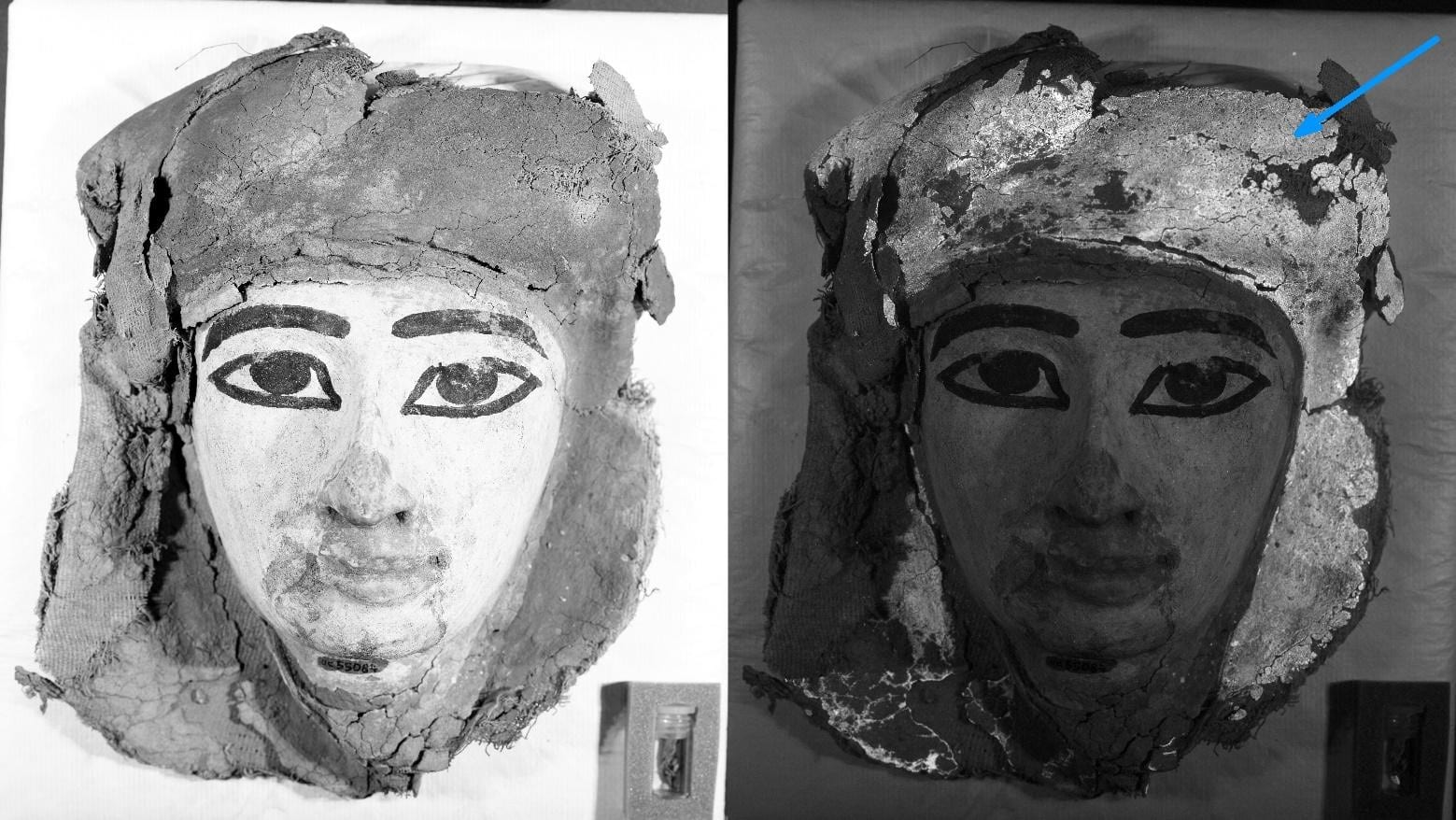

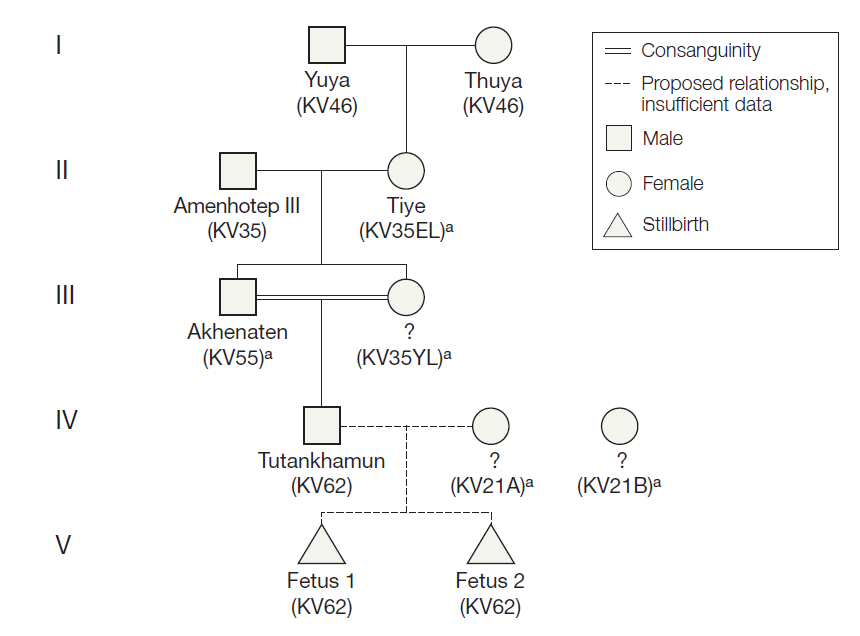

But let’s go back to the 18th dynasty (1549/1550 BCE to 1292 BCE). In 2010, a team of Egyptian and German researchers analysed 11 mummies dated from the 18th dynasty which were closely related to Tutankhamun (Hawass, Zahi, et al.). The mummies were scanned and DNA extraction on bone tissues was carried out. The information they could get from these analyses enabled them to identify the mummies, determine the exact relationships between members of the royal family, and to speculate on possible illnesses and causes of death.

The results of the DNA analyses show that Tutankhamun was, beyond doubt, the child born from a first-degree brother-sister relationship between Akhenaten and Akhenaten’s sister (see Fig. 3). Moreover, the authors provided an answer to the androgynous appearance of Akhenaten. They actually showed that the feminized appearance exhibited by the art of the pharaoh Akhenaten (also seen to a lesser degree in the statues and reliefs of Tutankhamun) was not related to some form of gynecomastia or Marfan syndrome as suggested in the past. Neither Akhenaten nor Tutankhamun were likely to have displayed a significantly bizarre or feminine physique. The particular artistic representation of persons in the Amarna period is more probably related to the religious reforms of Akhenaten.

However, the incestuous relationship between Akhenaten and his sister may have had other consequences. Pharaoh Tutankhamun suffered from congenital equinovarus deformity (also called ‘clubfoot’). The tomography scans of Tutankhamun’s mummy also revealed that the Pharaoh had a bone necrosis for quite a long time, which might have caused a walking disability. This was supported by the objects found next to his mummy. Did you know that 130 sticks and staves were found in its tomb?

Fig. 3: Genealogical tree showing the relationship between the tested mummies dating from the 18th dynasty (Source: Hawass, Zahi, et al.).

Fig. 4: Scans of Tutankhamun feet (Hawass, Zahi, et al.)

Incest and common people

This article on consanguinity and incestuous marriages could easily finish here. We learned that incest was practised in ancient Egypt for strategic reasons, in order to preserve the symbolism which associates the pharaoh to a living god. We also saw how science could help us in unravelling the true stories lying behind myths, speculations and rumours.

This could be almost perfect but the incest taboo is more complex than this. As observed by Paul John Frandsen, “in a society (such as ancient Egypt) where nuclear family incest is practised there is no discrepancy between what is licit among royalty and in the populace”. Indeed, contrary to what is often admitted incest was not only reserved to the ruling class. In Persia and ancient Egypt, incestuous relationships between members of non-royal nuclear families also existed (Frandsen P. J.). This shows that incestuous relationship in the nuclear family could be more than just propaganda and that other reasons might have motivated this practice. It has been argued that this was done for economic reasons as endogamy could have been a means to keep the estate undivided and/or avoiding paying bride price. However, these arguments have been dismissed. Up till now, there is thus no reasonable explanation for the lack of incest taboo in ancient Egypt and Persia.

Keep an eye out for my next post, where I’ll talk about incest in the Habsburg royal family and King Charles II of Spain (also called “the Bewitched”)!

References (and read more!)

Bouchard, Constance Brittain. Those of My Blood : Creating Noble Families in Medieval Francia. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Chauveau, Michel.MmNm. Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra : History and Society under the Ptolemies. Cornell University Press, 2000.

Hawass, Zahi, et al. “Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family.” JAMA, vol. 303, no. 7, 2010, pp. 638–647.

Frandsen, Paul John,MmNm. Incestuous and Close-Kin Marriage in Ancient Egypt and Persia : an Examination of the Evidence. Museum Tusculanum Press, 2009.

Close

Close