The Legal Manuscripts of Lambeth Palace Library

By Arendse I Lund, on 19 December 2018

For the past couple months, I’ve been working with the legal manuscripts at Lambeth Palace Library. As the historic library and record office of the Archbishops of Canterbury, they have an incredible collection of documents and manuscripts collected, copied and published from the 9th century till today — and I’m taking full advantage of it!

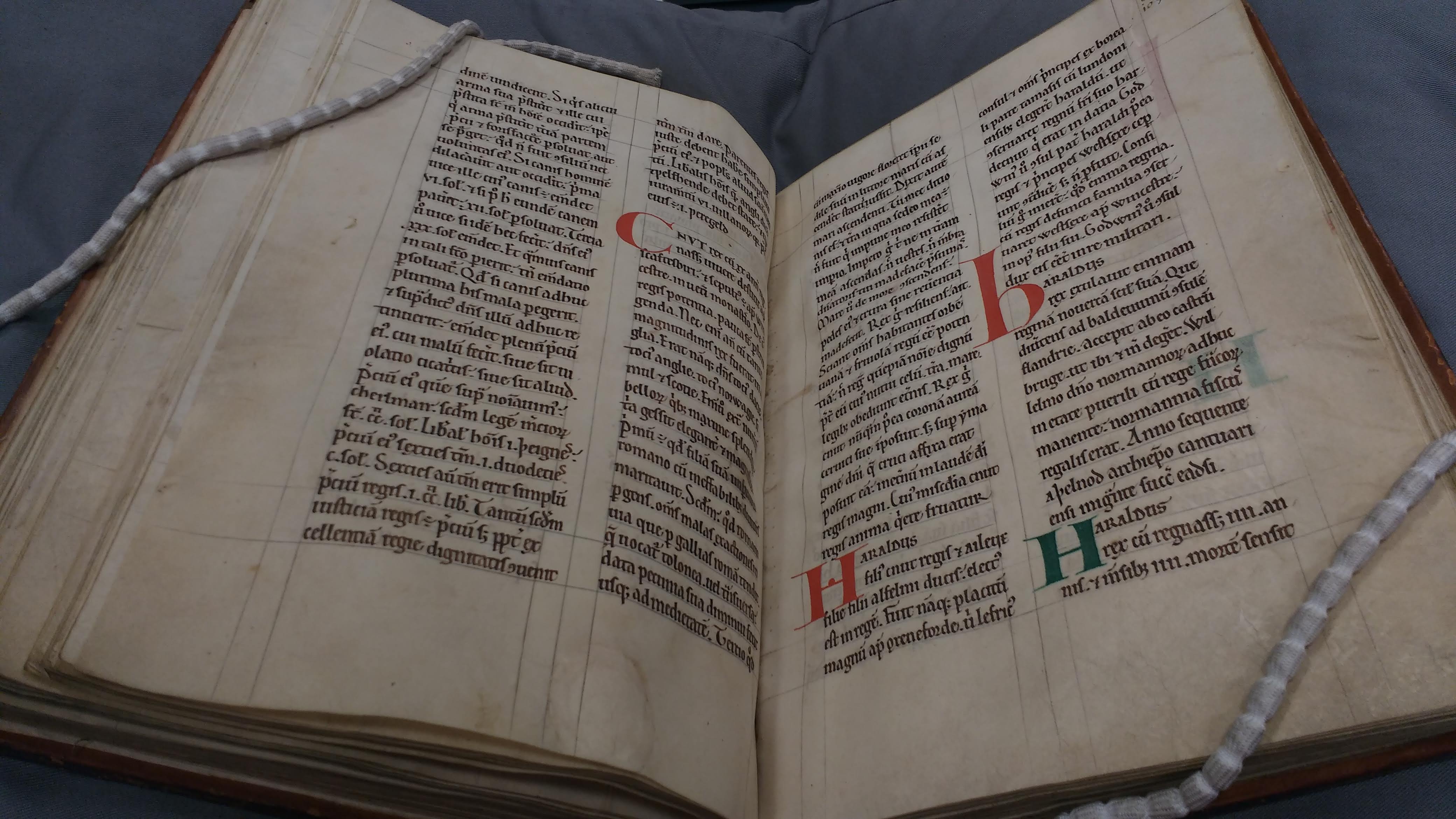

During my London Arts & Humanities Partnership placement at Lambeth Palace Library, I’m writing about the sorts of things I discover as I examine their incredible collection of manuscripts. My first piece is on their two vellum copies of Henry of Huntingdon’s massive Historia Anglorum, his account of the history of England from its beginnings until the mid-twelfth century. Huntingdon’s account is important as a historical source. However, it’s also fascinating because we can see his narrative techniques at play; he inserts apocryphal stories as a way to highlight a historical figure’s character.

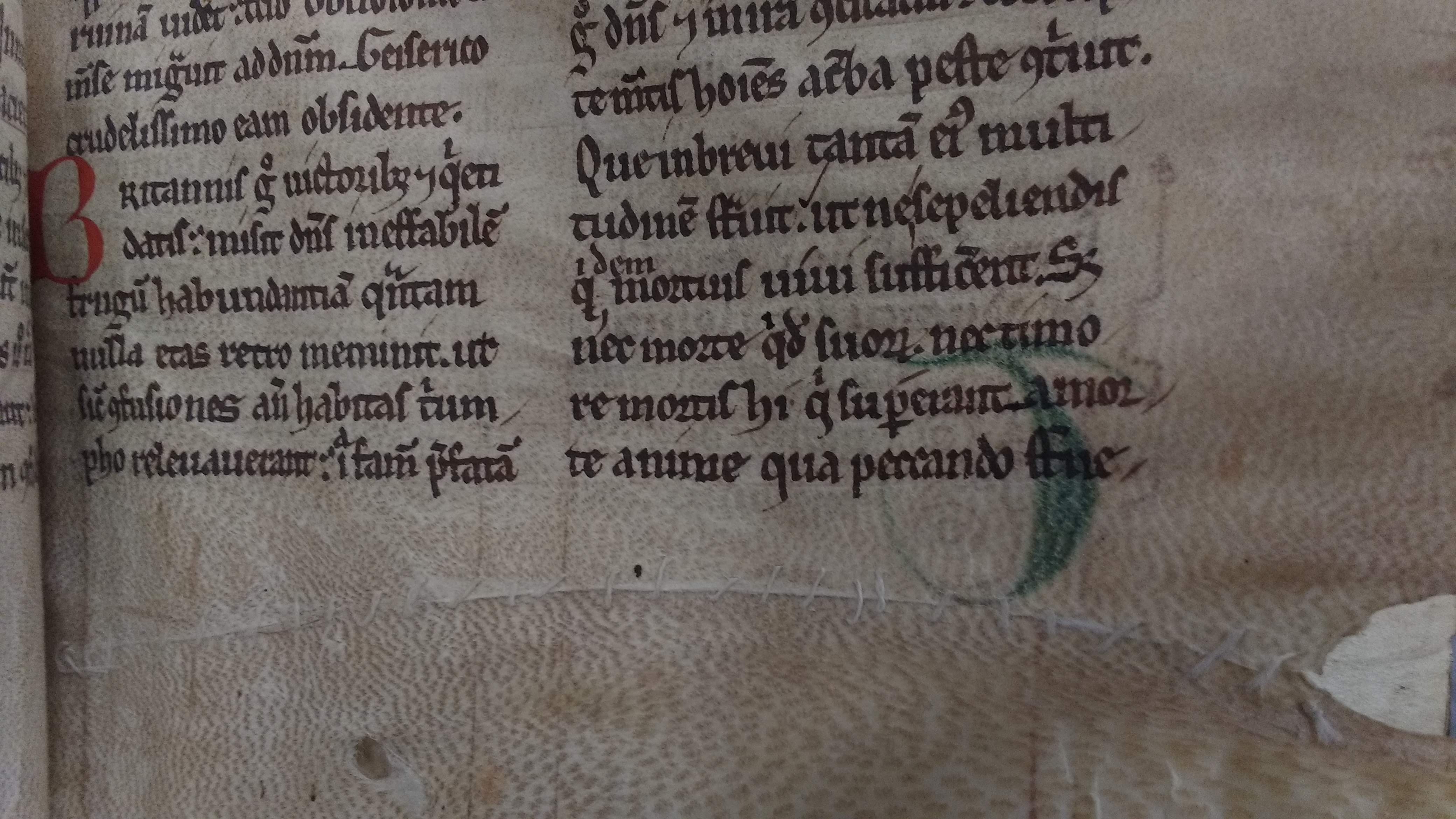

By comparing the two manuscripts their stark differences are thrown into light, both in terms of their content and also their current physical state. MS 118 is in a much better state with clean pages and wide margins. MS 327 has all the marks of having been a working copy and frequently used; there’s a spattering of verdigris discoloring the pages and stitches repairing tears in the vellum.

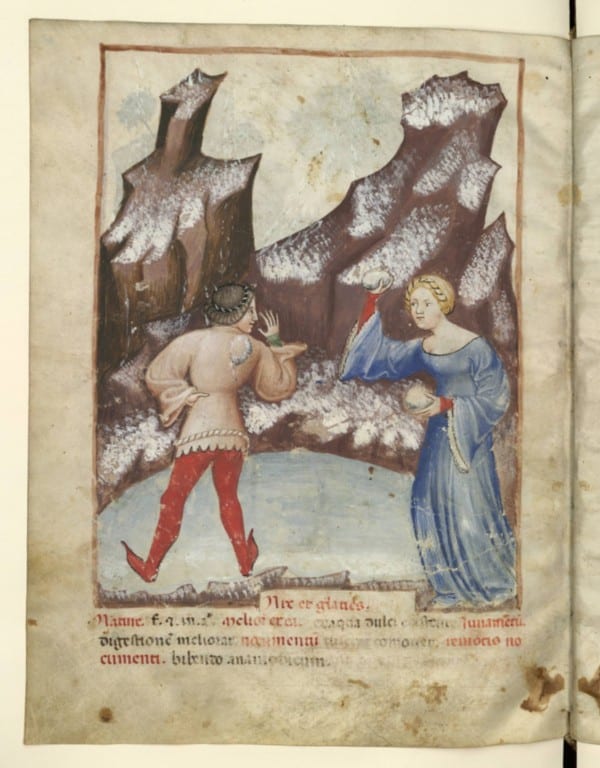

As I work my way through all of Lambeth’s medieval legal holdings, I am putting together an exhibit of the most important manuscripts. This will go on display in the spring. Stay tuned!

Close

Close