On the Origin of Pokémon Species

By Arendse I Lund, on 27 July 2016

by Arendse Lund

by Arendse Lund

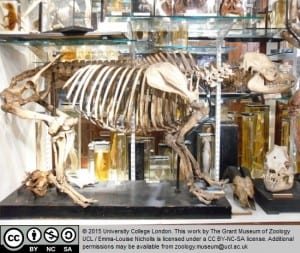

Last week, I was in the Grant Museum of Zoology when a cry came that a Pokémon had been spotted! Mobiles out, the visitors advanced on the creature and succeeded in capturing it. Surrounded by zoological specimens meticulously collected over centuries, here were people amassing their own digital collection of creatures. From a mouse that shoots lightning bolts to a shellfish that poisons with its lick, these creatures, collectively called Pokémon, take a variety of forms and all have different abilities. Many of these Pokémon are based on real animals.

For example, take Drowzee: These psychic Pokémon eat dreams and are based on the chiefly nocturnal tapirs, animals indigenous to tropical America and Southeast Asia. Tapirs have short legs and the Malayan tapirs are two-toned just like their virtual counterparts; they also have long, flexible snouts which allow them to grab foliage beyond their reach and even act as a snorkel when swimming. The Japanese word for tapir, baku, refers to both the zoological animal and a spirit in folklore which consumes dreams—just like its Pokémon counterpart.

For example, take Drowzee: These psychic Pokémon eat dreams and are based on the chiefly nocturnal tapirs, animals indigenous to tropical America and Southeast Asia. Tapirs have short legs and the Malayan tapirs are two-toned just like their virtual counterparts; they also have long, flexible snouts which allow them to grab foliage beyond their reach and even act as a snorkel when swimming. The Japanese word for tapir, baku, refers to both the zoological animal and a spirit in folklore which consumes dreams—just like its Pokémon counterpart.

Another example are Sandslash, which have long claws for burrowing, feature brown quills covering their bodies, and will roll into a ball in order to defend themselves from attack. These Pokémon take their inspiration from the pangolin, which are sometimes referred to as scaly anteaters. However, they are more closely related to giant pandas. The name derives from the Malay word pengguling, meaning “something that rolls up.” They have overlapping keratin scales armoring their backs, with tails strong enough to hang from trees, and a tongue that, when extended, is longer than its body. These incredible creatures are found in Asia and Africa but are sadly the most trafficked animals in the world.

Another example are Sandslash, which have long claws for burrowing, feature brown quills covering their bodies, and will roll into a ball in order to defend themselves from attack. These Pokémon take their inspiration from the pangolin, which are sometimes referred to as scaly anteaters. However, they are more closely related to giant pandas. The name derives from the Malay word pengguling, meaning “something that rolls up.” They have overlapping keratin scales armoring their backs, with tails strong enough to hang from trees, and a tongue that, when extended, is longer than its body. These incredible creatures are found in Asia and Africa but are sadly the most trafficked animals in the world.

Then there’s Seel, which evolves into Dewgong. In these two Pokémon, everything’s in the names: The former is based off of a seal and the latter a dugong. In appearance, dugongs are similar to manatees but both male and female dugongs grow two tusks—this is reflected in its adorable Pokémon counterpart. The semi-nomadic dugongs’ habitat extends throughout the Indo-West Pacific but they mostly stay in the bays around Australia; their conservation status is listed as vulnerable due to overdevelopment of the coastal areas and excessive fishing. Dugongs derive their name from the Malay word duyung, meaning “lady of the sea” and the species is possibly the origin of the mermaid myth.

Then there’s Seel, which evolves into Dewgong. In these two Pokémon, everything’s in the names: The former is based off of a seal and the latter a dugong. In appearance, dugongs are similar to manatees but both male and female dugongs grow two tusks—this is reflected in its adorable Pokémon counterpart. The semi-nomadic dugongs’ habitat extends throughout the Indo-West Pacific but they mostly stay in the bays around Australia; their conservation status is listed as vulnerable due to overdevelopment of the coastal areas and excessive fishing. Dugongs derive their name from the Malay word duyung, meaning “lady of the sea” and the species is possibly the origin of the mermaid myth.

There are many more examples of the real-life basis for Pokémon: axolotl for Mudkip, tadpoles for Poliwag, and racoons for Zigzagoon, to name just a few. The creator of Pokémon, Satoshi Tajiri, was heavily influenced by the type of creatures he found while insect collecting as a child. He used to sneak out into rice paddies and look under rocks for beetles. In a 1999 interview, he bemoaned the disappearance of those paddies and said of his love for the outdoors, “As a child, I wanted to be an entomologist. Insects fascinated me. Every new insect was a wonderful mystery. And as I searched for more, I would find more. If I put my hand in a river, I would get a crayfish. Put a stick underwater and make a hole, look for bubbles and there were more creatures.” These findings influenced many of the creatures that would make up the Pokémon world.

As both the Grant and Petrie Museums are PokéStops, it’s great to see people encouraged to check out the museum collections as they pursue their Pokémon. Perhaps most fascinating of all, these virtual Pokémon collections now spark conversations with strangers over techniques and the best places to acquire rarer species in a strikingly similar way to amassing physical collections of any sort.

And any avid collector, be it of stamps or insects, can understand the lure of the Pokémon slogan: “Gotta catch ‘em all!”

Close

Close