Colours of Ancient Egypt – Blue

By Anna Pokorska, on 16 October 2018

This is the second in the Colours of Ancient Egypt series; if you want to start at the beginning, click here.

The colour blue has already featured in a couple of posts in this blog (e.g. check out Cerys Jones’ post on why the Common Kingfisher looks blue) but it seems impossible to me to discuss colour, especially in Ancient Egypt, and not start with blue. Arguably, blue has the most interesting history of all the colours, which can be attributed to the fact that it is not a colour that appears much in nature – that is, if you exclude large bodies of water and the sky, obviously. Naturally occurring materials which can be made into blue colourants are rare and the process of production is often very time-consuming. In Ancient Egypt, pigments for painting and ceramics were ground from precious minerals such as azurite and lapis lazuli; indigo, a textile dye now famous for its use in colouring jeans, was extracted from plants.

Left: two pieces of azurite (Petrie Museum, UC43790); Right: lapis lazuli (Image: Hannes Grobe)

However, all the above-mentioned colourants presented issues which limited their use. Azurite pigment is unstable in air and would eventually be transformed into its green counterpart, malachite. Lapis lazuli had to be imported from north-east Afghanistan (still the major source of the precious stone) and the extraction process would produce only small amounts of the purest colourant powder called ultramarine. Finally, indigo dyes can fade quickly when exposed to sunlight.

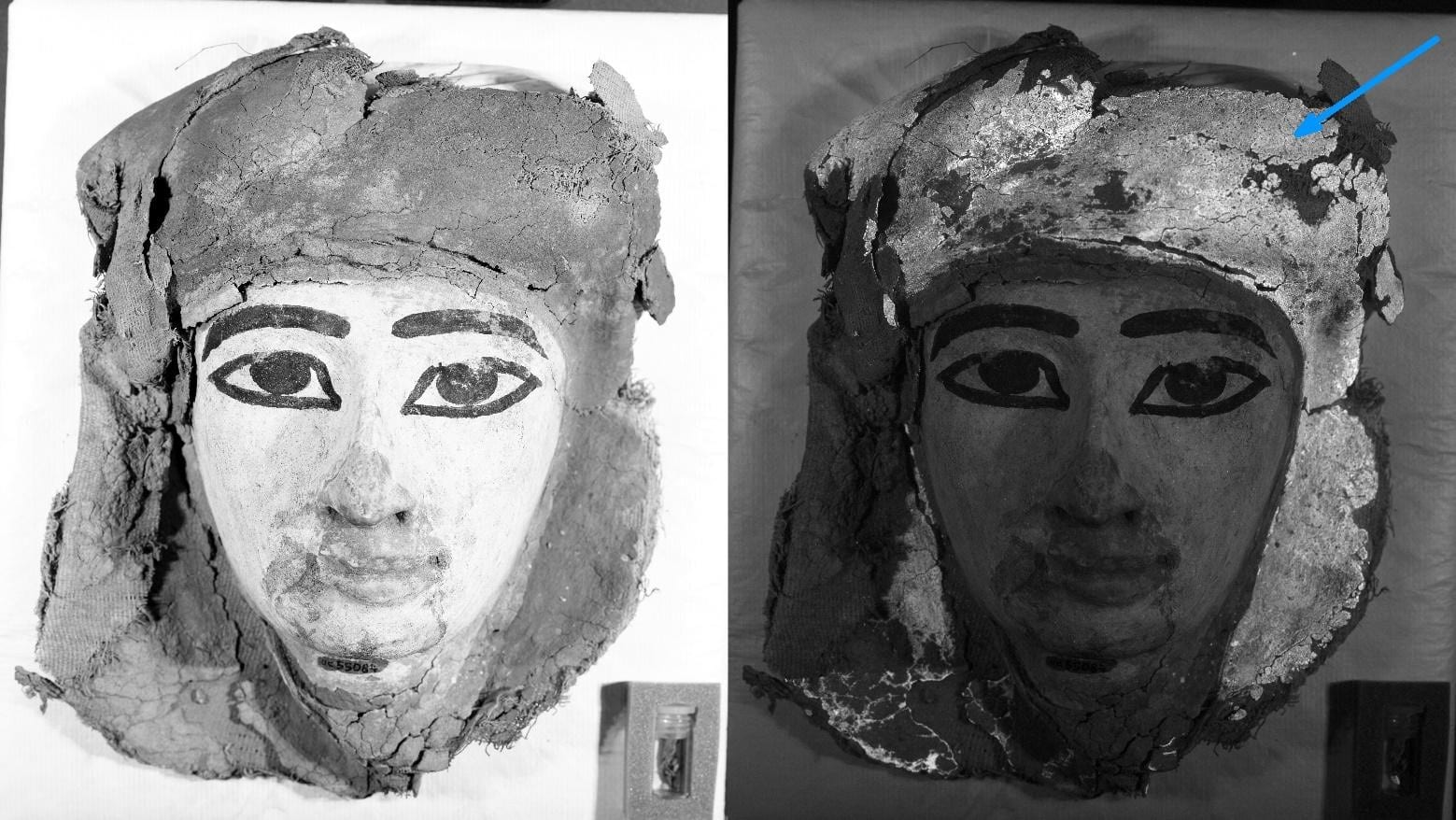

And yet it seems that the Ancient Egyptians attributed important meaning to the colour blue and it was used in many amulets and jewellery pieces such as the blue faience ring, lapis lazuli and gold bracelet or the serpent amulet from the Petrie Museum collection (below).

From left to right: blue faience ring with openwork bezel in form of uadjat eye (Petrie Museum, UC24520); lapis lazuli serpent amulet (UC38655); fragment of bracelet with alternative zig-zag lapis lazuli and gold beads (UC25970).

Therefore, the race to artificially produce a stable blue colourant began rather early. In fact, the earliest evidence of the first-known synthetic pigment, Egyptian blue, has been dated to the pre-dynastic period (ca. 3250 BC)[1]. It was a calcium copper silicate (or cuprorivaite) and – although the exact method of manufacture has been lost since the fall of the Roman Empire – we now know that it was made by heating a mixture of quartz sand, a copper compound, calcium carbonate and a small amount of an alkali such as natron, to temperatures over 800°C.

Fragment of fused Egyptian blue (Petrie Museum, UC25037).

This resulted in a bright blue pigment that proved very stable to the elements and was thus widely used well beyond Egypt. In fact, its presence has recently been discovered on the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum due to its unusually strong photoluminescence, i.e. when the pigment is illuminated with red light (wavelengths around 630 nm) it emits near infrared radiation (with a max emission at 910 nm).

After its disappearance, artists and artisans had to make do with natural pigments and, being the most stable and brilliant, ultramarine became the coveted colourant once again. In fact, during the Renaissance, it is reputed to have been more expensive than gold and, as a result, often reserved for the pictorial representations of the Madonna and Christ. And so, the search for another replacement was back on. But it wasn’t until the early 1700s that another synthetic blue pigment was discovered, this time accidentally, by a paint maker from Berlin who, while attempting to make a red dye, unintentionally used blood-tainted potash in his recipe. The iron from the blood reacted with the other ingredients creating a distinctly blue compound, iron ferrocyanide, which would later be named Prussian blue. Naturally, other man-made blue pigments and dyes followed, including artificial ultramarine, indigo and phthalocyanine blues.

However, it wasn’t quite the end of the line for Egyptian blue, which was rediscovered and extensively studied in the 19th century by such great people as Sir Humphry Davy. And not only are we now able to reproduce the compound for artistic purposes, scientists are finding more and more surprising applications for its luminescence properties, such as biomedical analysis, telecommunications and (my personal favourite) security and crime detection[2].

References:

[1] Lorelei H. Corcoran, “The Color Blue as an ‘Animator’ in Ancient Egyptian Art,” in Rachael B.Goldman, (Ed.), Essays in Global Color History, Interpreting the Ancient Spectrum (NJ, Gorgias Press, 2016), pp. 59-82.

[2] Benjamin Errington, Glen Lawson, Simon W. Lewis, Gregory D. Smith, ‘Micronised Egyptian blue pigment: A novel near-infrared luminescent fingerprint dusting powder’, Dyes and Pigments, vol 132, (2016), pp 310-315.

Close

Close