Diagnosing Foreign Bodies

By Gemma Angel, on 25 March 2013

by Sarah Chaney

by Sarah Chaney

One of the most important diagnostic tools to assist in foreign body removal was the development of the x-ray. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen, a German physics professor, developed the x-ray photograph, which enabled the interior of the body to be made visible using electromagnetic radiation.[1] In the late 1890s and early 1900s, medical reports on foreign bodies frequently focused on the use of the “Röntgen Rays” or “skiagraphs” (as x-rays were then widely called) to locate such objects. A few weeks after Röntgen published the first X-ray photograph, Norman Collie at UCL made his own x-ray tube in order to locate a broken needle in the thumb of a female patient.

World’s first diagnostic x-ray, by Norman Collie at UCL.

UCL Special Collections, on display in the Octagon Gallery

until 30 April: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/whats-on

Many of the foreign bodies case histories in hospital records of the period focus on the use of this new diagnostic technique. However, x-rays could also lead to tension between patients and clinicians, when the photographs contradicted stories told by patients. One German publication of 1899 reported a soldier’s claim to have been bitten by a horse as “malingering” (a serious military crime) when broken needles were found in the wound, suggesting that the injury was self-inflicted.[2]

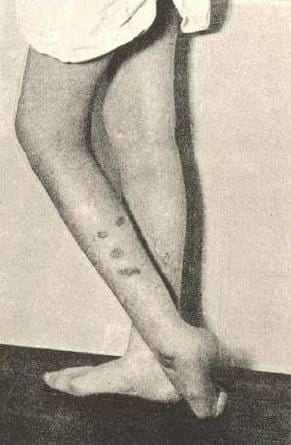

Image showing self-inflicted burns in a

“hysterical” patient, from John Collie’s

Malingering and Feigned Sickness (1913)

Yet, surprisingly (given the widespread publicity given to so-called malingering in civilian populations in the decades preceding the National Insurance Act of 1911), these stories seem to have been of less interest to many surgeons than the diagnostic procedure itself. At the Royal London Hospital in 1898, for example, little interest was shown in the fact that the x-ray photographs of 38-year-old domestic servant Elizabeth Quaife did not tally with the history she gave.[3] Elizabeth claimed that she had suffered pain in the knee joint ever since a long hat pin ran into her leg while she was sweeping under a bed: in hospital, however, five separate needles were discovered in the joint. Unlike in published cases, the surgeon made no reference to the potential use of x-ray imagery to detect fraud, but instead used the case to evaluate the usefulness of the technique itself. This, it was thought, had been successful in locating and removing four needles but “the fifth needle shewed by the skiagraph was … not found. It is probable that the figure shewed in the skiagraph was due to a shadow of the other needles. This, once more, shews that the skiagraph may be deceptive.”

This emphasis on diagnosis and removal certainly tallies with the lack of interest surgeons tended to show in the cause of foreign bodies. Foreign Body in this period was a diagnosis, not an exploration of a patient’s state of mind. When Rachel Taylor was admitted to the Royal London in 1900 – after swallowing a pin and a tin tack – and again in 1906 having swallowed two nails “the night before last”, it was not noted whether either instance was accidental or intentional.[4] Despite published concern over the potential abuse of charitable treatment, in practice this does not seem to have been a significant issue for either surgeons or physicians at the Royal London Hospital: cases of “artefact injury” were treated without question whether or not the patient paid for their treatment.

References:

[1] Lisa Cartwight, Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995)

[2] “Self-Inflicted Injuries Diagnosed by the Roentgen Rays,” The Lancet, 153, no. 3955 (1899): 1668.

[3] Elizabeth Quaife, RLHA Microfilm Case Records (Surgical), DEAN F1898, pt. no. 29 & 511.

[4] Rachel Taylor, RLHA Microfilm Case Records (Surgical), TAY F1900, pt. no. 2326 & FENWICK 1906, pt. no. 906.

Close

Close