‘smoke words languishing and melting in the sky’ — Stress: Remembrance, Trauma, Forgetting

By uclznsr, on 23 November 2015

by Niall Sreenan

This talk was delivered on the 11th of November 2015, at the UCL Art Museum, at a public event addressing remembrance and the exhibition “Stress: Approaches to the First World War”. It has been reproduced here largely unedited other than an expanded final paragraph and the addition of bibliographic references.

In the wake of recent events in Paris and Europe, an afterword has been appended by the author.

‘smoke words languishing and melting in the sky’ — Stress: Remembrance, Trauma, Forgetting

Walk west from where we sit now, past UCL’s Front Lodge, down the Euston Road, past Great Portland Street underground station, and you will come to a location of great historical violence and a site of present remembrance. At 12.55pm on the 20th of July 1982 a bomb planted by the Provisional IRA exploded under a bandstand in Regent’s Park, killing seven members of the British Army. The soldiers, members of the Light Infantry Battalion, the Royal Green Jackets, were playing a scheduled performance of the music of Oliver!

Today, there exists a plaque in the same location that is both dedicated to the lives of the men who perished in that attack and which commemorates this act of brutality. The plaque reads: ‘To the memory of those Bandsmen of the 1st Battalion The Royal Green Jackets who died here as a result of a terrorist attack’. It is both a commemoration of life and a marker of death – one of many waypoints of remembrance that punctuate the public spaces of London. The specific wording of this particular remembrance plaque is significant here for it surely inflamed the righteous anger of the perpetrators of this heinous violence – and perhaps deliberately so. Members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army did not view themselves as “terrorists”, as such, but as members of a legitimate armed force attempting to land a cruel blow against a nation whose armed forces occupied what they considered their sovereign state.

In the wake of the attack, the Provisional IRA took responsibility for their actions and made a proclamation that turned the rhetoric of then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher against her own people. They declared: ‘The Irish people have sovereign and national rights which no task or occupational force can put down.’ In asserting this, the IRA insisted they were merely repeating the very same appeal to national sovereignty Thatcher did to justify the British action in the Falklands war. The point of this act of rhetorical ventriloquism, for the IRA, was to legitimate their terror by framing it in terms of the language of international politics, and to muddy the difference between terrorism and any other “legitimate” act of war.

The plaque that adorns the bandstand in Regent’s Park, then, is not merely a marker of remembrance for the violence of that day, but a politically contentious reminder of a controversial war that took place thousands of miles away, of the lives lost there too, and of the way in which remembrance – the way in which we remember death and conflict – is always itself political. Today this plaque stands immovable and dumb, as inanimate as the well-oxidised bronze-roofed bandstand to which it is attached – and yet, it practically hums with the polyphonic dissonance of competing historical and political voices – as well as those of the dead.

Take a seat on a bench nearby in Regent’s Park and another set of voices makes itself heard. These voices are imaginary – but no less real for that – and these too provide an opportunity to remember. One, a soldier, Septimus Warren Smith, decorated for bravery, returned to London from the First World War. The other, Lucrezia Renzi, a 24 year old Italian hatmaker whom Septimus met while billeted in Milan following the armistice in 1918. They married soon after.

And on a bright June day in Virginia Woolf’s modernist masterpiece, Mrs Dalloway, Septimus, ‘pale-faced, beak-nosed, wearing brown shoes and a shabby overcoat’, and Lucrezia, ‘a little woman, with large eyes in a sallow pointed face’, sit on a public bench somewhere in Regent’s Park avoiding the bustle and noise of the city. They gaze upwards at the sky where a plane writes messages, white puffs scrawled against the blue tablet of the sky.

‘So, thought Septimus, looking up, they are signalling to me. Not indeed in actual words; that is, he could not read the language yet; but it was plain enough, this beauty, this exquisite beauty, and tears filled his eyes as he looked at the smoke words languishing and melting in the sky and bestowing upon him in their inexhaustible charity and laughing goodness one shape after another of unimaginable beauty and signalling their intention to provide him, for nothing, for ever, for looking merely, with beauty, more beauty! Tears ran down his cheeks.’

This moment of sublime happiness is, for Septimus, a momentary consolation for he is a sufferer of what, in the 1920’s, we called shell-shock. He is beset on all sides by perceived threats and visions of horror, and blighted by images of his departed friends and comrades. He talks to himself, talks to the dead, and sees their faces in trees. He threatens to kill himself.

Woolf’s novel, which, among other things, depicts Septimus and Lucrezia’s trip to London to visit a doctor specializing in the treatment of the mentally infirm, acts as yet another form of remembrance. It is a fictional monument to the effects of the war on its survivors – on the soldiers that made it home – as well as on those who lived with these men, those who picked up the fragments of what was left of Europe in the wake of this First World War. What is distinctive about Woolf’s form of remembrance is that, unlike a plaque or cenotaph or another monumental concrete hulk, it is a supple and ambivalent form of remembrance. She neither offers judgement on an enemy or on a victim, and provides a perspective on the suffering of the First World War from within – from the subjective perspective of the sufferer who is also a killer, Septimus, and from the perspective of an innocent who must also bear that suffering, Lucrezia.

Woolf describes one particular moment in which Septimus submits entirely to his delusions:

‘He sang. Evans answered from behind the tree. The dead were in Thessaly, Evans sang, among the orchids. There they waited till the War was over, and now the dead, now Evans himself —

“For God’s sake don’t come!” Septimus cried out. For he could not look upon the dead.

But the branches parted. A man in grey was actually walking towards them. It was Evans! But no mud was on him; no wounds; he was not changed. I must tell the whole world, Septimus cried, raising his hand (as the dead man in the grey suit came nearer), raising his hand like some colossal figure who has lamented the fate of man for ages in the desert alone with his hands pressed to his forehead, furrows of despair on his cheeks, and now sees light on the desert’s edge which broadens and strikes the iron-black figure (and Septimus half rose from his chair), and with legions of men prostrate behind him he, the giant mourner, receives for one moment on his face the whole —“But I am so unhappy, Septimus,” said Rezia trying to make him sit down.’

Woolf depicts with terrible alacrity the horror-stricken, jumbled phenomenology of the shell-shocked Septimus, never deigning to explain or make coherent the set of visions and confusions to which he is subject. The scale and intensity of the trauma Septimus re-experiences is made clear: legions of the dead occupy a vast desert, watched over by a giant figure, a mourner of vast and monumental scale. On the other hand, this poetry of grief, its tacit sympathy for the griever, is interrupted and cut short by the rather more prosaic, if no less profound, melancholy of the griever’s wife. Lucrezia, struggling to keep Septimus earthbound, articulates in much more simple terms her fundamental dissatisfaction of life – ‘I am so unhappy’.

The passage, then, allows us to read – to sympathise with – both sides of a conflict. Not a war, as such, but the tension or opposition between Lucrezia’s profound unhappiness at life lived in constant battle with a shell-shocked war hero, as well as Septimus’s life lived out of joint, haunted by visitations from a traumatic, violent past.

Remembrance – or perhaps more accurately – memorialization, is always polyvalent. Monuments, whether they are dynamic and deliberately ambiguous, as Woolf’s work undoubtedly is, or solid and monolithic, as in the stone monuments dedicated to violence and suffering sitting in public spaces, are traversed by choruses of competing voices – each straining to tell a story that goes beyond our capacity as societies and individuals to remember. Whether we as individuals and a society prefer the monolithic and stoic silence of stone or the ephemeral, ambivalence of poetic discourse, is a question of what we understand by remembrance. That is to say, what is the purpose of remembrance, and what is its value?

At this stage I want to turn to the work of Friedrich Nietzsche whose understanding of history and remembrance is somewhat at odds with that of our own time. In the second of his Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche takes the example of the contentment of animals, which live ‘unhistorically’ in a state of constant and pure present, and contrasts this with the tortured uncertainty of humankind whose slavery to history is a crippling encumbrance. We are, he writes, ‘all suffering from a consuming fever of history’ and ought, he believes, at the very least, begin to recognise this.

What happens in the past, Nietzsche believed, constantly and unproductively irrupts into the present, disrupting our lives in ways that are injurious to any possible feeling of contentment. ‘[I]t is a matter for wonder’, he writes, ‘a moment, now here and then gone, nothing before it came, again nothing after it has gone, nonetheless returns as a ghost and disturbs the peace of a later moment.’ However, far from wishing to entirely negate the value of historical knowledge at all, Nietzsche is railing against an obsessive relation to the historical which renders us as societies and individuals incapable of acting – of moving forward. As compulsive rememberers, constantly reflecting and ruminating on what has passed, we are in a state of sleeplessness, incapable of forgetting, and stuck in a state of paralysis.

This paralysis is recognisable in sufferers of PTSD or shell-shock, the primary, and most cruel symptom of which, is an inability to forget. Sufferers are visited and revisited, against their will, by images and memories of traumatic events from their past, forced to relive – over and over – the very events which caused their current paralysis, their submission to the horrors of the past.

Septimus is haunted by the death of his friend and fellow soldier Evans. He sees him in the park; he hears his voice from behind a screen; Evans stands silently outside his bedroom window. Septimus sees in the flowers that line the river banks near Hampton Court a sea of floating lamps. This brings to mind what Edward Grey, former British Foreign Secretary, is said to have remarked on the eve of the First World War: ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time’. But for Septimus, no such extinguishing of memory is available to him. We mark remembrance in Europe with the lighting of candles, the reconstitution of the light that was lost in War, but Septimus is doomed to live in a constant state of remembrance, the constant re-illumination of violence and horror, the only escape from which is the absolute blackness found in death.

There is a tension then in our desire to remember, our obsessive need to commemorate, the deaths of soldiers and the horrors of war. The adage ‘Never forget’ is perhaps the emobdiment of our ideology of remembrance. This takes on a sinister hue in light of what Nietzsche tells us of the dangers of history and what know now about the reality of post-traumatic stress: those afflicted by this awful condition are afflicted by precisely this – they never can forget.[1]

Forgetfulness is precisely what Nietzsche recommends to us as the remedy for obsessive remembrance. ‘To shut the doors and windows of consciousness for a while; not to be bothered by the noise and battle […] a little peace, a little tabula rasa of consciousness to make room for something new […] there could be no happiness, cheerfulness, hope, pride, immediacy, without forgetfulness.’

How then, as a society, can we avoid consigning ourselves to a state of societal post traumatic stress disorder. How can we remember the dead, commemorate their lives, and manage also to forget – to allow ourselves to move on?

The key, in Nietzsche’s terms, lies in the difference between active forgetting and passive forgetting. To passively forget the past is to submit oneself to it, irrespective of its value to the present. In passively forgetting, we let slide from view – or repress – that which is both difficult to apprehend and which is of value to a society today: complexity, ambivalence, the conflicted multi-perspectival historical dynamics that get lost in the shadow of a monument. We consign ourselves in this passive mode of forgetting to remembering by imitation – by repetition – obsessively recreating and insisiting on the authenticity of our remembrance.

In contrast, to actively forget is to allow the possibility of those ambiguities and complexities obtain in the present and to allow ourselves to stop being haunted by the monolithic, or reified form of history, that simplifies what happened in the past.

Here then, the way in which the monolith functions suddenly becomes clearer. It is a form of passive forgetting – enacted in remembrance. The inscription on the plaque in Regent’s Park, remembering the dead from that awful attack 23 years ago, is passively aggressive – couching its sentiment in remembrance but in reality consolidating an ideological and political statement that, whatever its accuracy, brooks no argument. It is an obsessive remembering of certain details, a refusal to let past conflicts recede from view, making forgiveness impossible in the face of the monolithic reminder of a heinous violence.

And in contrast, the literary word, the shifting meaning of poetic writing, ‘languishing and melting in the sky’, does the opposite. The details it depicts are, of course, selective. But, in contrast with the monolith, the reader’s assimilation, interpretation, and response to the memories it invokes is also selective – one has the option, when reading Woolf’s account of Septimus and Lucrezia, to sympathise with the plight of women, to meditate on the horrors of shell-shock and the inhumane way in which it was treated in the 1920s and beyond; we can, as readers, both marvel in the suppleness and energy of Woolf’s prose while simultaneously recognise the horror of what she describes. Literary language is ephemeral and polysemous – and therefore does not allow itself to become set in stone – it does not dictate its meaning to us or inscribe and official memory but rather invites us to draw on our own memories and create our own meanings.

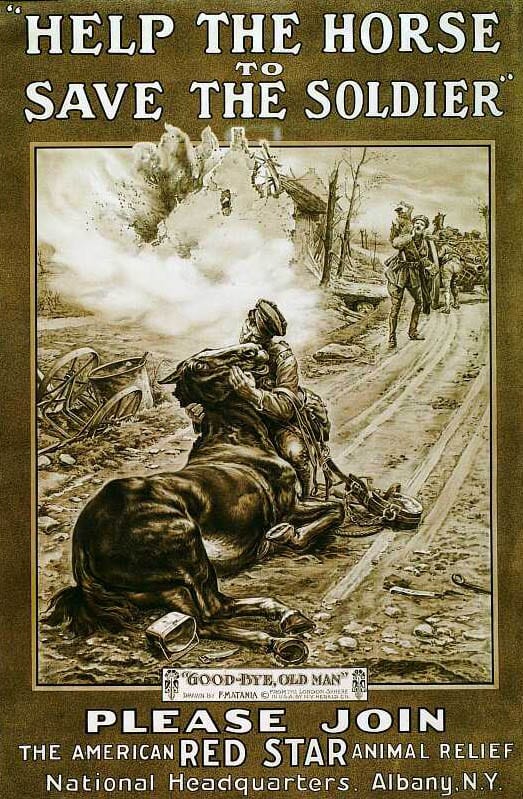

This is how I conceived, curatorially speaking, of our modest exhibition in UCL’s North Lodge. In creating an exhibition about – or in relation to – the First World War, we are, in effect, creating a form of remembrance. However, the exhibition space, the objects, and the object labels are not there to instruct but to act as a springboard or space for the possibility of discourse and questions. This is why my own choice of objects, Noel’s phrenology heads and Leonard Darwin’s photos of soldiers bequeathed to the Galton Institute, testify to the hidden bio-political valences of imperial warfare. Monolithic statues do not remember the eugenic arguments made by Leonard Darwin, which stated that the wholesale destruction of young men at the front could only be countered by an active campaign to mobilise the reproductive faculties of women on the home front. Remembering the unremembered – stressing the unstressed – allows us, not to replace the prevailing narrative of remembrance, but to add to it a set of voices that are so often quietened amidst the din of trumpets and hooves.

This is also why, when we as a group conceived of the exhibition, we wanted the “public engagement” aspect to be integral to the exhibition itself – and not as an afterthought. The presence of PhD researchers in the space at all times, to engage with the questions of visitors and to describe their own personal and disciplinary approach to curation, allows the space to be filled with a multitude of voices. The objects, the stories behind them, the interdisciplinary approach to understanding the war, and the questions and anecdotes of the visitors; these all work, I hope, to make the exhibition function as a monument in which remembrance can be enacted openly and actively.

[1] It was pointed out to me afterwards that the adage ‘Lest we forget’ is more usually associated with the First World War (it is lifted from Laurence Binyon’s poem “For the Fallen” published in The Times in 1914) and would thus render my argument here slightly more complicated. The equivocal “lest” registers a sense of trepidation at what might happen should we ever entirely efface the memory of war and its victims. In contrast, “never” is both an appeal to a transcendental or eternal form of remembrance and a super-egoic injunction, something more akin to an order than a form of questioning. That said, the phrase ‘Never forget’ has gained a form of popular currency and is frequently used in conjunction with forms of remembrance in the USA – for 9/11, the Holocaust, Pearl Harbor – perhaps deriving from a speech given by Benjamin Franklin in which he urged ‘May we never forget’. That ‘Never forget’ came to mind as I wrote this piece might reflect my lack of erudition in relation to this period of history but equally might also reflect the way in which remembrance today is more often than not undertaken in the spirit of a disciplinary injunction than in the spirit of open inquiry.

Afterword – 19th November, 2015

Since delivering this talk on the Armistice Day, the 11th of November 2015, the atrocities committed in Paris and further abroad have thrown this essay into a new light. I thought carefully about whether it was appropriate or not to post this so close to the traumatic events themselves, when the grief, emotion, and outrage these killings demand has yet to give way to the forms of remembrance I tried to explore and question in my presentation earlier in the month. It is not my desire to undermine the anger, the horror, and the sadness which has characterised the Europe-wide and worldwide response to the attacks in Paris, the attacks in Beirut, and characterises our response to brutally violent terrorist attacks anywhere, at any time, or of any political persuasion. And it was certainly not my intention in this essay to directly address the myriad political issues and the symptoms of trauma and remembrance that blight the Middle East and which periodically irrupt into European society.

However, if anything, it is now more crucial than ever to remember and to do so actively – to engage in acts of communal commemoration and solidarity – and to do this in the spirit of open, reasoned, and empathic inquiry that such a complex incident requires. The atrocities in Paris are the horrific culmination of a number of different and often conflicting historical, ideological, and civilisational currents – or voices. Let us not, in our desire to remember the dead, drown out the voices of the living and the oppressed and the other.

Armistice Day is celebrated and remembered not to glorify war but to celebrate peace. Let us hope we will have the opportunity to do so again soon.

Works Cited and Consulted:

Encyclopedia of Terrorism, ed. by Peter Chalk (Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2013).

Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, Trans. by R. J. Hollingdale, Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, Trans. Douglas Smith, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Peter Radamanovic, “From Haunting to Trauma: Nietzsche’s Active Forgetting and Blanchot’s Writing of the Disaster” in Postmodern Culture, 01/2001; 11(2).

Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, Modern Classics, (London: Penguin, 2000).

Close

Close

This post is associated with our exhibit

This post is associated with our exhibit