In short, we think so…

In the archaeological record, ‘cannibalism’, also known as ‘anthropophagy’, is usually identified through studying human bones and analysing any cut marks left on them that were made by stone tools. These cut marks would have occurred during the process of de-fleshing, or excarnating, the individual.

Cutmarks are used as evidence of cannibalism and have been reported at several different Neanderthal sites, like El Sidron and Goyet Cave; however, incontrovertible proof of intentional cannibalism is relatively rare. When analysing marks on bones, archaeologists observe the taphonomy of the find; this means trying to untangle what has happened to it since it was deposited from its systemic (or life-time) context. In some cases, reports of cutmarks made by Neanderthals have been re-analysed and interpreted as damage from carnivore activity or environmental processes.

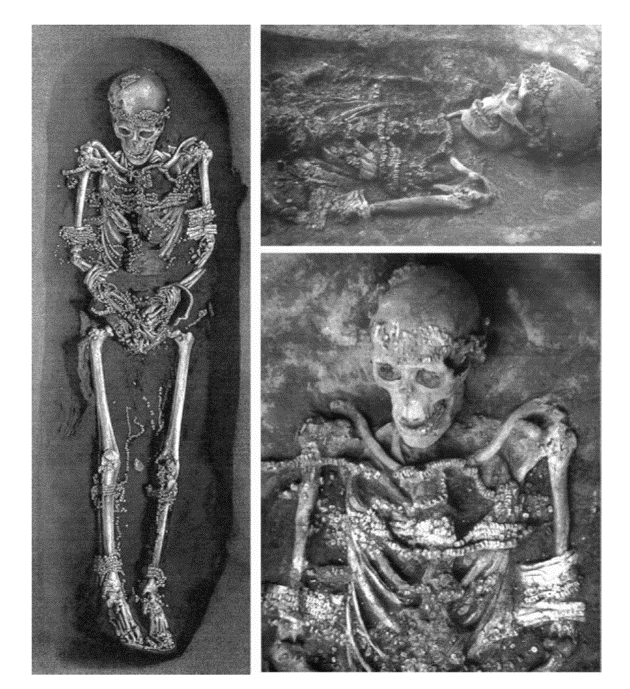

Cutmarks are found in predictable patterns. For example, upper limbs are usually disarticulated (removed from the body) whereas lower limbs, which have a higher nutritional value, are de-fleshed. At Goyet Cave in Belgium, cutmarks found on Neanderthal rib bones have been used to suggest evisceration and removal of the chest muscles (Rougier et al. 2016). There is also evidence of percussion marks on thigh bones where they have been struck to extract the bone-marrow, which is highly calorific.

The main evidence for brain-eating derives from cut marks and percussion marks found on Neanderthal crania, suggesting skulls were exploited to get to the brain, which is also a very nutritious organ.

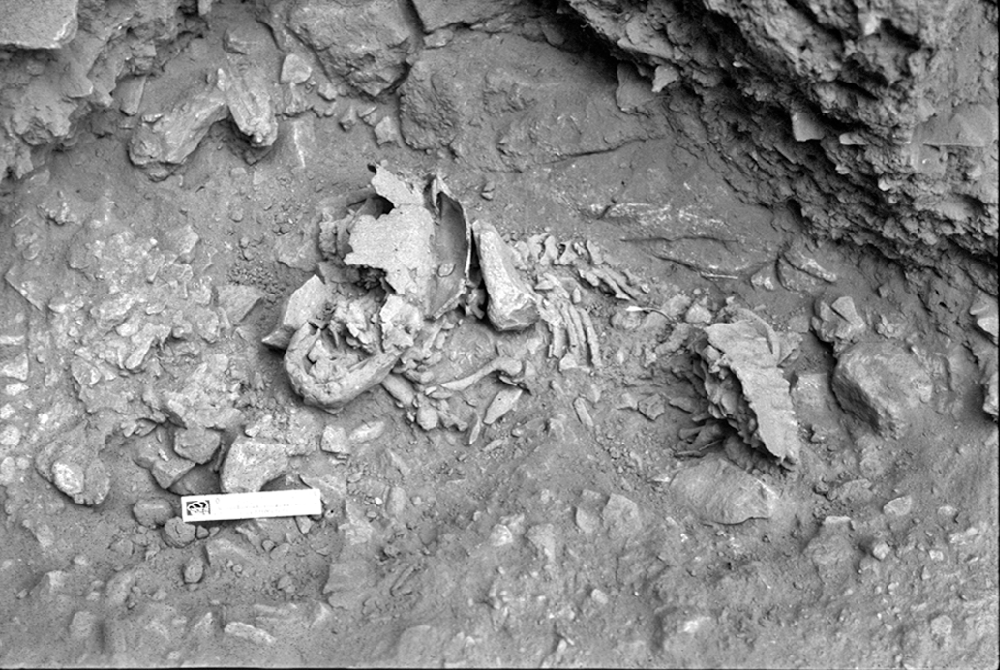

Figure 1: A summary of all the cutmarks and percussion marks/pits recorded on the Neanderthal remains from the Troisième Caverne of Goyet (Belgium). Note the prevalence of cutmarks on the calorific areas of the femur and tibia. (Image reference: Rougier, H., Crevecoeur, I., Beauval, C., Posth, C., Flas, D., Wißing, C., Furtwängler, A., Germonpré, M., Gómez-Olivencia, A., Semal, P. and van der Plicht, J., 2016. Neandertal cannibalism and Neandertal bones used as tools in Northern Europe. Scientific reports, 6, p.29005)

Human bones often occur alongside animal remains and one of the most important criterion for identifying cannibalism is whether both types of bones have been treated in the same way. If this is the case and human bones are butchered just like animal bones, then it’s likely that nutritional cannibalism took place.

It’s hard to say whether all Neanderthals practised nutritional cannibalism as we know that their behaviour varied across different regions and timescales. It may have been a behaviour that occurred out of necessity during periods of nutritional-deficit, when sufficient animal and plant resources were scarce.

What are the repercussions of anthropophagy?

Anthropophagy is taboo and it’s a bad idea to eat people; in a modern context it’s socially unacceptable but there are also potential health issues particularly related to eating certain parts of the body.

Eating brains can expose you to prions, a type of protein generally found in the central nervous system. Everybody has them, however some types of prion can act as infectious agents inducing abnormal folding of otherwise healthy prions. These abnormal prions can occur through genetic inheritance, sporadic mutation, or infection.

The brain is the most vulnerable organ if exposed to infectious prions. Abnormal folding causes the degeneration of white matter, making the important parts of the brain spongy. This explains why prion diseases are neurodegenerative, causing symptoms like loss of co-ordination (cerebellar ataxia) and muscle control. They are fatal and there is no current cure.

You might have heard of the prion diseases Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (CJD) or Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE – ‘mad cow’ disease). One of the reasons that the BSE scare occurred in the ‘90s was that farmers were feeding cattle a form of slurry that was made by combining the carcasses of other livestock, greatly increasing the living animal’s likelihood of ingesting infected brains or parts of the nervous system. This became illegal and when the practice stopped so did the elevated cases of BSE.

Probably the most famous outbreak of prion disease is the Kuru, which originated amongst the Fore tribe in Papua New Guinea. In Fore, Kuru literally means ‘the shakes’ referring to loss of muscle control. It’s believed that Kuru originated from one individual in the tribe who experienced a sporadic prion mutation but that it spread so effectively because the Fore practiced ritual anthropophagy until around 1950. Anthropophagy was a key part of their mortuary practice as it involved both honouring and passing on the strength of the deceased. Kuru was most prevalent in women and children as they consumed most of the nervous system and were responsible for the practical excarnation of the dead. At its height, the Kuru epidemic killed around 2% of the Fore women annually.

If you’ve played the video game Far Cry Primal, the tribe based on Neanderthals, ‘The Udam’, suffer from the fictional terminal disease ‘skull-fire’ that is probably inspired by Kuru. This disease is instrumental in their ensuing demise and the supremacy of modern humans (in the video game!).

Neanderthals likely lived in small family groups and were highly mobile. Therefore it seems unlikely that a prion disease could become ubiquitous and have had long-term impacts on their overall survival as a species. Although there are fringe theories that do suggest this, there are many Neanderthal remains found without signs of cannibalism. As more information about genetics and population dispersal becomes available, it seems very unlikely that the assimilation/extinction of Neanderthals was down to prion disease.

The reason that Kuru was so established within the Fore tribe is a combination of both the presence of infectious prions and a very established routine of ritual cannibalism. Basically, eating more brains does not cumulatively give you prion disease but if you do consume brains the probability that you will ingest a brain that has infected prions is much higher – making you much more likely to catch a prion disease.

Anatomically modern humans and ritual cannibalism.

Ritual cannibalism is harder to recognise in the archaeological record than nutritional cannibalism and, so far, hasn’t concretely been reported in Neanderthal populations. However, osteoarchaeological finds from a site in Southern England called Goughs Cave strongly imply that anatomically modern humans practiced ritual cannibalism. The evidence is quite gory with bones even showing signs of being chewed by other humans! Ritual cannibalism is suggested because three of the skulls were shaped to create cups or bowls and one bone has been engraved.

So yes, Neanderthals probably did eat brains, but so did our more modern ancestors, perhaps something to think about if you’ve been looking into trying out the palaeodiet…

Reference:

Rougier, H., Crevecoeur, I., Beauval, C., Posth, C., Flas, D., Wißing, C., Furtwängler, A., Germonpré, M., Gómez-Olivencia, A., Semal, P. and van der Plicht, J., 2016. Neandertal cannibalism and Neandertal bones used as tools in Northern Europe. Scientific reports, 6, p.29005.

Close

Close