What do Kids ask Scientists?

By ucbtch1, on 26 January 2018

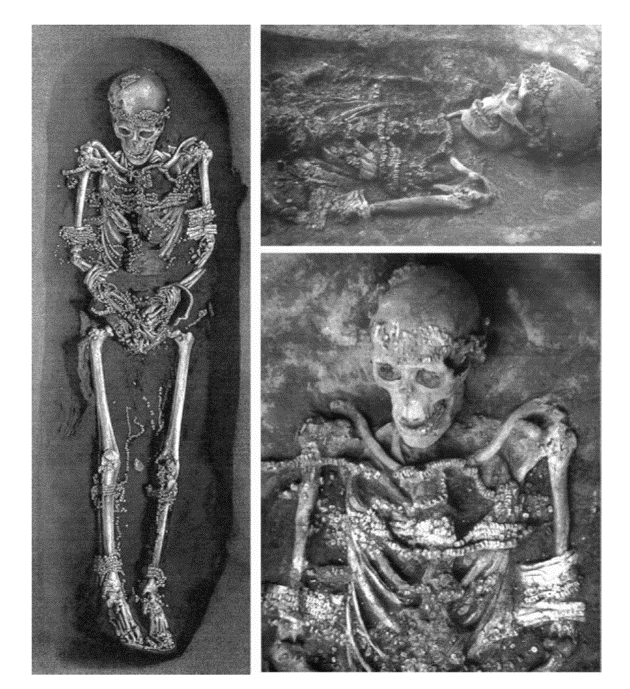

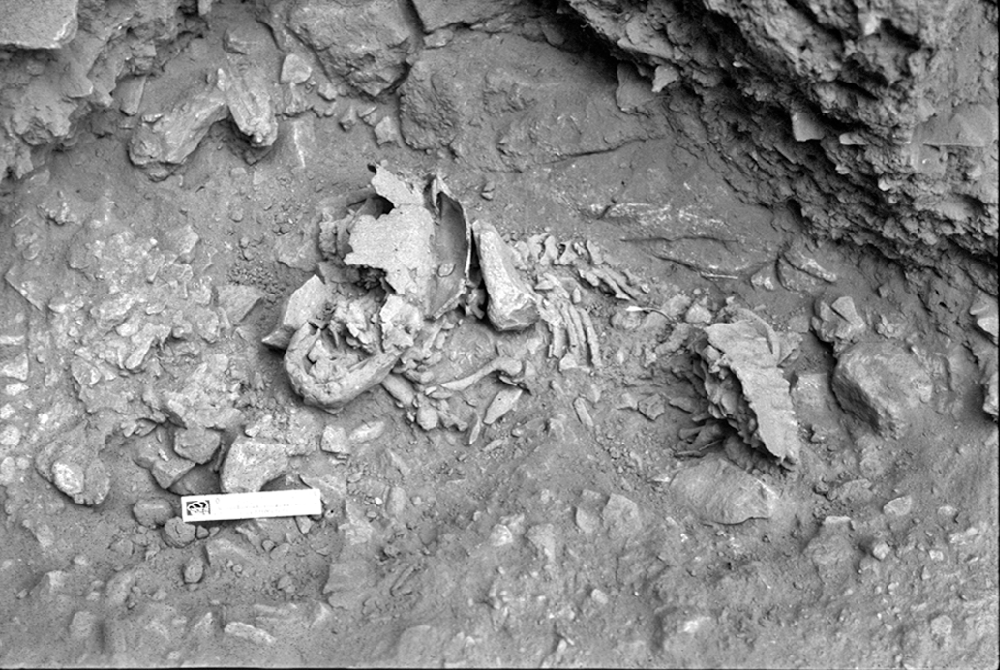

Science is exciting, science is fascinating, and with science you never get bored — this is what I want to communicate to children when I give talks about my research. As I work with brains, lasers and 3D printing, that’s easy enough. When I talk about neuroscience and what I do in the lab as a PhD student, kids are always interested even if the younger ones don’t even know what a brain does. When I show them pictures of my research (see below), which involves working with brain cells and dissecting brains, there’s always an eww sound — because the brain is “slimy”.

A pig’s brain, which — according to kids — is gross because it’s slimy. (Image: Author’s own photo)

The same brain cut into pieces. (Image: Author’s own photo)

After my talk, with just a couple of minutes left and a lot of hands raised, I get a lightning round of questions. They range from all aspects of life, not just science as they assume that scientists know everything about everything in the universe. This would be cool, but it’s definitely not the case. Anyhow, I always have a blast answering their unique questions, so I’ve decided to share a couple of my favourites and some of the trickier ones here. Here is a taster of them, followed by my inner dialogue (ID) and what I actually answered (A). As you will see, my inner dialogue can be quite different from the answer, which just shows how difficult it can be to answer unexpected questions. Remember, as I always tell the kids, there are no stupid questions.

Q: Can you make little animals?

ID: Other than little humans in my uterus, no.

A: Scientist are trying to make organs in the lab by growing cells in a specific way, but we can’t grow a full animal yet.

Q: Why do you die?

ID: Because our bodies can’t cope with so much wisdom.

A: It’s a big scientific question, trying to answer why we age and ultimately die. Our bodies grow older and our cells don’t regenerate as much as they used to, but ultimately we don’t know exactly why this happens.

Q: How much do you make?

ID: Not enough.

A: Enough.

Q: Is it true that when you die your heart explodes?

ID: Yes, if you die in an explosion.

A: No, when you die your heart just stops beating.

Q: Can we even get to fully understand the brain if it’s always evolving?

Now, this one really impressed me because: 1) she knows about evolution and understands that not only we as a species evolved but we are still evolving and so are our brains; 2) she knows that we don’t know everything about the brain; and 3) it’s just a really interesting question coming from a 10-year-old!

ID: Wow, yeah that’s true, can we?

A: That’s a very good question. Yes, we don’t know fully how the brain works but there are breakthroughs in science every day and new tools and techniques will allow us to one day fully understand the brain, even if it’s still evolving.

Q: My friend told me that he saw a ghost and… (After a long story about his friend seeing a ghost, the teacher was a little fed up with his not very scientific question and the rest of the class was giggling).

ID: I’m also giggling.

A: Just because your friend said so that doesn’t mean it’s real. You have to question him and ask him to show you evidence of what he claims is true. Remember to always question everything and look for evidence.

Q: What’s the most interesting thing you’ve discovered?

ID: How resilient I can be when facing relentless adversity, demonstrated by how my numerous failed experiments and negative results have broken my spirit yet have not killed my wandering scientific mind. Oh, wait, you mean like in science?

A: How cool neurons look down a microscope.

Q: Why do you like gross stuff?

ID: What are you talking about? Brains are not gross, they’re amazing!

A: What are you talking about? Brains are not gross, they’re amazing!

Q: How old is the universe?

ID: Oh god, try to remember, you know this.

A: Around 14 billion years.

Q: How much is that?

A: A lot!

So there you have it: kids and their questions. I wish to thank the schools that invited us PhD students, as well as the children for listening to me and asking such stimulating questions. Keep your curiosity alive!

Close

Close