Question of the Week:

Was Using Human Remains for Science Taboo?

By ucramew, on 20 January 2016

By Misha Ewen

During a shift in the Grant Museum of Zoology recently, an American high school student asked me about the history of the collection and how it has been (and still is) used to teach students about anatomy. We got on to talking about museum collections that have specimens of human remains, like the Hunterian Museum in London. His next question was, when did we stop feeling that studying human remains through dissection, for the purposes of science, was taboo?

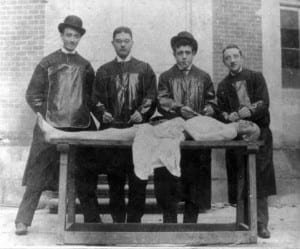

Nowadays, it’s commonplace for students studying anatomy to encounter human remains as part of their university degree, but this wasn’t always the case. In the early nineteenth century, there was a dire shortage in Britain of bodies for the purpose of medical research. For instance, the Edinburgh Medical College received fewer than five cadavers a year [1]. This was because only the remains of executed criminals could legally be used. The limitations put on scientific research because of this policy gave oxygen to the criminal business of ‘body-snatching’. When it began, the ‘snatchers’ invented a method to remove bodies from graves without detection: they used to dig holes, some distance away, and tunnel down into the graves before pulling bodies out by rope or hooks. Those who could afford it soon began to invest in mausoleums, vaults and table tombstones to ensure the safekeeping of their eternal resting places [2].

The business of bodysnatching, that fuelled medical research, soon turned even more sinister… In 1831 three men were arrested in London for the murder of vagrants, individuals whose deaths they thought would go unnoticed. On the day they were arrested, they had tried to sell the body of a fourteen year old boy to the lecturers of King’s College for twelve guineas [3]. There was also the famous case of William Burke and William Hare in Edinburgh, who murdered seventeen victims between 1827 and 1829, before selling the corpses to Dr Robert Knox at the Edinburgh Medical College. Unfortunately, this grisly business was inherently tied up in the advancement of medical knowledge.

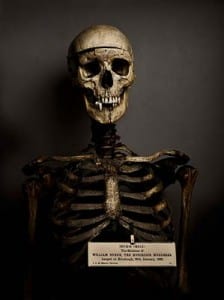

The dissection of bodies was problematic, in both religious and moral terms, for contemporaries. In the first instance, many believed that their bodies had to remain intact for the afterlife, and dissection was also widely considered to be a punishment for the worst type of criminal. Take the fate of the Edinburgh bodysnatcher William Burke, for instance: he was executed by hanging in 1829 and his body was then publicly dissected at the Edinburgh Medical College [4]. And yet, in this period, recognition of the need for medical students to learn from human subjects was growing.

Public outcry, because of the black-market that had developed around medical research, helped the passing of a new bill: the 1832 Anatomy Act, which recognised that more bodies were needed for research and teaching. University College London’s Jeremy Bentham, who donated his own body to science (his auto-icon remains in the UCL South Cloisters), helped prepare the bill before his death in 1832. The act significantly extended access to cadavers, by allowing anatomists to dissect ‘unclaimed bodies’, individuals who died without anyone coming forward to pay for their burial. This was mostly people who died destitute in hospitals, workhouses and prisons. Dissection was no longer solely associated with individuals who were executed for murder, it was now also associated with the shame of dying in poverty [5].

It was really only in the mid-twentieth century that the donation of bodies to science became commonplace. Yet even now, we often feel squeamish about donating our bodies to science after we die. Attitudes certainly have changed, however, since 1832. From December 2015, individuals living in Wales will now have to opt-out if they don’t want their organs donated when they die, and legislation will certainly change soon in the rest of the United Kingdom.

[1] http://www.edinburgh-history.co.uk/burke-hare.html

[2] http://www.history.co.uk/study-topics/history-of-death/the-rise-of-the-body-snatchers

[3] http://www.exclassics.com/newgate/ng609.htm

[4] http://www.edinburgh-history.co.uk/burke-hare.html

[5] http://www.kingscollections.org/exhibitions/specialcollections/charles-dickens-2/italian-boy/anatomy-act

Further reading:

Colin Blakemore & Sheila Jennett, ‘body snatchers’, The Oxford Companion to the Body (2001). Encyclopedia.com. <http://www.encyclopedia.com>.

Close

Close