The Politics of the Mortgage Market in Mongolia

By ucsadul, on 29 January 2016

This is the third blog post in a series about debt and loans.

In the beginning of December 2015, news headlines declared that commercial banks would stop providing housing mortgages at a favourable 8 % interest rate. The “8 % interest housing mortgage” (8 huviin oron suutsny zeel) is a nation-wide programme initiated and implemented by the government through commercial banks. The government started the programme in 2013 as a means to increase the affordability and accessibility of apartments for urban residents, particularly young families and those living in the ger districts. The news of the repeal was shocking for many because it froze people’s ability to acquire apartments while also signalling a wider crisis in the national financial system.

Social demand for housing

A friend of mine, B, was planning to sell his flat to his friend in order to buy a larger flat from a different friend. The friend who was planning to buy B’s flat was about to receive a bank-approved mortgage. Because he was very certain to get a loan from the bank, and since the selling and buying arrangements were between friends, they decided to exchange apartments before getting all the paperwork finalised. B moved into his friend’s flat while his friend who had the mortgage approved moved into his former flat. A few days afterwards they all heard the news that banks would no longer be offering mortgages with 8% interest rates. All of them went into a panic and they sought advice from friend who works in the banking industry to find out whether the repeal was a temporary or a permanent policy decision. They asked two friends, one working in the Khan Bank and another working in the State Bank (Toriin Bank), and both assured based on internal bank information that the repeal would not last long.

There is a widespread belief that mortgages allow people who live in ger districts to purchase apartments with low-interest loans, thereby decreasing air pollution in the whole city. However, this does not seem to be the main trigger. The economist Batsuuri, for example, has claimed that people living in ger areas are not the major purchasers of apartments. So while such programmes appear to address social problems, they are also a business opportunity for others.

Monopoly of mortgage market

According to the employee at the State Bank, the bank is the most important, largest, and dominant bank constituting part of Mongolia’s financial system. There are no other major institutions that compete with banks in the whole financial system in Mongolia. Moreover, in the bank, the major financial activity is mortgage loans. According to him, banks cannot function without mortgages. Consequently, stopping the 8% mortgage program might further cause collapse in the ‘financial system’ (sankhuugiin togtoltsoo), because people would not be able to afford to purchase apartments at higher interest rates. Not only him, but many other professionals working in Mongolian banks were very certain that the repeal would not last long for the sake of the sustainability of the financial system.

As I am not an expert on banking and financial systems, I am not in a position to comment in detail here. However this repeal creates an impression that commercial banks profit from mortgage loans and are protected by the existing financial system and high social demand for housing. It is in fact a consequence of the capitalist system brought up in Mongolia since the 1990s that exploits debtors and protect creditors. Bank monopoly was one of the two major arguments the constitution court developed and it became a trigger for the association of banks to decide to repeal the 8% mortgage loan scheme.

In fact the repeal of the 8% mortgage was not an immediate decision. Before it was publicly revealed in the news there was a discussion that occurred in the constitutional court. Civilians D. Yanjinkhorloo and B. Enkhbayar made complaints against some articles in the law regarding bank and non-bank financial service centres (NBFS) mortgage agreements. The complaints address how contracts based on the existing law regulates real estate (flat, house and land) mortgage does not permit civilians to go to court in the case when they are not able to pay loans and dispossesses mortgage property without having judicial decision.

The constitutional court discussed the case, concluding that some articles in the law of real estate mortgage violated a clause in the constitution regarding rights to possess real estate. According to the constitution, any cases of dispossession of real estate property should go through a court decision. Therefore, the constitutional court meeting announced that the law of real estate mortgage violates basic human rights, as declared in the constitution. The constitutional court asked parliament to amend the law and fix the violation. This decision was made on the 9th of December. It required the Association of Commercial Banks to react quickly, indefinitely stopping such mortgages. The constitutional court also raised other issues why the law around mortgages needed to be amended. The court considered that bank and NBFS loans and mortgages violated articles in the law against unfair competition. 17 commercial banks and NBFS dominate loan and mortgage services in Mongolia, by occupying more than the 1/3rd of the mortgage market. According to the law against unfair competition, article 5.1., defines any case of sales and services of more than 1/3rd of the market to be dominating it and, therefore, should be stopped.

For example, commercial banks gain profit from the interest gained on mortgages. As MP S. Ganbaatar puts it in his numerous public talks and parliament speeches: ‘dogs get fat when zud comes’ (zud bolohod nohoi zoolno), – i.e. dogs get fat when there has been a severely cold winter from feeding on the carcasses of dead livestock. This alludes to the profits banks are making when normal people are suffering, and is a reason why he comments that all banks should be called ‘pawn shops’ (lombard).[1] It is indeed noticeable that many Mongolian and foreign business people, including some politicians, have opened banks or NBFS in Mongolia.

Political immunity of mortgage business

The above-mentioned friend who works in a bank further explained that a well-known national company, Bodi International, owns a certain percentage of shares of Golomt Bank. Lu. Bold who is the founder and owner of this company is also an MP and a minister. A news article from 2010 revealed some of the owners of this bank, but many are not known.

The banker further revealed that a very large national company, the Tavan Bogd Group, and other foreign companies, such as ‘Savada Holdings’ from Japan, are owners of the Khan Bank (the latter owns the largest portion at 53%). Another article from 2014 refers to bank owners as usurers (mongo huulegchi). The same term was used in the early 20th century to identify Chinese and Manchu high-interest money-lenders. The article reveals that ‘Global Investment and Development’ owns the largest share of 65 % of the Trade and Development Bank. The article speculates that the ex-President N. Enkhbayar and MP J.Battulga, who owns the ‘Jenko’ company, also have shares in the bank. These are the largest three banks in Mongolia.

It is not only professionals working in the banking sector and journalists who try to find out who are the owners of these large banks and accuse them of being usurers. Many others in fact have the same opinion. Around the time when I was conducting field research in Dundgovi aimag, Batbayar, a young man who worked in Turkey, told me about Islamic Banks that allow loans with no interest. Batbayar, suggested that this is what Mongolia currently needs if the state is truly attempting to support housing and small- and middle-range enterprises, rather than allowing commercial banks to ‘spin money’.

As we can see mortgages are highly politicised and are not simply economic or social, especially at the moment when Mongolia is only a few months away from the next parliamentary elections in June. As Kh. Batsuuri states: ‘mortgage problem is becoming an advantage for rulers near the election’. Alongside amendments to the Mortgage Law, ruling Democratic Party leaders have decreased mortgage interest rates from 8 % to 5 %. Not long after, in the start of January 2016, this news received favourable comments from the public in the media. Some even openly declared that they would now vote for the Democratic Party, while others commented that this is rather a temporary ‘electioneering show’ (songuuliin show).

Absence of long-term policy making

On the 19th of January 2016, after about a month since the 8% mortgage loan was stopped, the Parliament of Mongolia approved an amendment to the Mortgage Law (Ul khodlokh ed khorongiin baritsaany tukhai khuuli). The amendment in article 27.1 now enables owners to have the right to issue permission to the mortgagee in cases when the mortgagees change ownership. This is not the only amendment. Interest rates have also decreased from 8 to 5 %, bringing possible future risk to the economy at large. As some economists, such as Kh. Batsuuri and J. Ganbaatar (PhD candidate at the American University)[2] explain, the mortgage loan should have financially supported itself without becoming a burden to the national economy if it had worked according to the original plan. Indeed, considering the current weak economic situation in Mongolia, Kh. Batsuuri questions whether the 3 % decrease in mortgage interest rates actually puts more pressure on Mongolia’s economy. According to his elaboration, the 8 % interest rate influenced the current economic crisis. For instance, the Mongolian government had to print more national currency in order to supply mortgage loans, which brought 13 % inflation, plus the price of flats dramatically increased.

The same critique has also been made by another economist, de Facto Jargalsaikhan. In his latest post he comments that ‘the technology to print more currency to develop the country is vigorously increasing in Mongolia’. Maybe there are many more economist who consider the 5 % interest mortgage a serious threat to the already weak national economy. It will possibly bring with it more currency printing, more inflation, more cheap mining deals, and more external debt, in addition to the existing more than 20 billion USD debt.

Speaker of Parliament Z. Enkhbold explains “why mortgage was stopped and what should be done”. Speaker of Parliament Z. Enkhbold explains “why mortgage was stopped and what should be done”. Source: http://economy.news.mn/content/232023.shtml

Speaker of Parliament Z. Enkhbold explains “why mortgage is crucial”. Source: http://sodon.mn/news/16035

According to the media, the decreasing interest rate of mortgages and their availability again, serves to satisfy those wanting to purchase an apartment, construction companies struggling to sell apartments, and commercial banks who make massive profits from mortgage interest rates. Passing this policy does not serve the potential damages that it might incur on the national economy. The only agent that consistently profits and is safely protected, by society, politics and the economy, are the commercial banks, owned by foreign investors and Mongolia’s oligarchs. They are indeed safely protected, firstly by the social demand for housing, and secondly by political decisions that meet public demands in order to receive more votes for the up-coming election, and thirdly the unstoppable financial system dominated and monopolized with loans.

The question that remains is; what was the politics behind changes to mortgages? Why were they stopped? Was it because of the constitutional court decision regarding the violation of basic human rights and monopolisation in the national economy? Or, was it actually the outcome of a genuine fight against the politically-empowered dominant business for the sake of fair competition? Or, further, was it in fact due to the political conflicts between large business owners and their political allies? Is the 5 % interest mortgage another short-term political play to gain support prior to elections? In this fractious political climate, who is actually taking care of the long-term interests of the national economy?

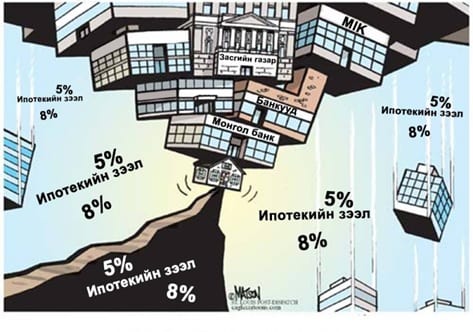

Mongolian banks teetering on the edge, with 5 and 8% mortgages crashing. Source: http://www.trends.mn/n/4709 (Original source: Modkraft)

[1] See also: https://www.facebook.com/ganbaatar.sainkhuu/videos/1089739141060523/?theater

https://www.facebook.com/ganbaatar.sainkhuu/videos/1089540537747050/?theater

For soyoljson lombard “culturalised pawn shops” also see http://www.fact.mn/204265.html

[2] Rebecca Empson and D. Bumochir’s skype interview with Ganbaatar Jambal, January 2016.

Close

Close