Alternatives to the IMF and China? Anti-offshore Movements and Debt Restructuring Possibilities

By uczipm0, on 6 June 2017

Sanchir is a political scientist and activist broadly concerned with economic and political development in Mongolia and in the Global South. His main area of research focuses on, but not limited to problems of late and uneven development, democratization process in post-socialist countries, issues of trade, and investment, extractivism, poverty and debt in the developing world. He has an interdisciplinary research agenda that combines political theory, global political economy, and Central Asian and Russian studies. This blog post originated in email conversations between Sanchir, members of the Emerging Subjects project, and Mongolia-focused scholars about the role of the IMF and China in addressing Mongolia’s economic crisis.

On May 24th, 2017 The Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a three-year extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for Mongolia to support an approximately $5.5 billion total financing package. Along with obtaining financing from the IMF to address Mongolia’s sovereign debt crisis, there was also the possibility of Mongolia receiving a straight loan from China; however, the Chinese side ultimately cancelled the deal. Many politicians, political commentators, and media outlets have promoted the arrangement with the IMF as a lesser of these two evils.

I have argued that presenting a bailout from the IMF or loans from China as the only options for Mongolia to address its economic situation is a false binary propagated by official discourse and a monopolized media. Notwithstanding the question of plausibility, different civil society organizations and individuals (including myself) have been invoking other possibilities. This includes alternatives such as returning embezzled money from offshore accounts[1]; auditing the use, distribution, and repayment of sovereign bond sourced credits; cutting unnecessary budget expenses and other measures of similar ilk.

The most prominent movement in Mongolia promoting theses aforementioned views has been the People’s Anti-Offshore Committee (‘The Committee’). Their biggest activity has been the protest of March 31st where several hundred people protested at Sukhbaatar Square over the alleged theft of public funds now held in offshore accounts. Politicians and activists at the protest demanded the return of $17 billion lying in these accounts. Even though some people have speculated that these protests were funded by some members of the ruling class in order pressure their opponents, the birth of different anti-offshore Mongolian groups abroad, as well as a large interest in the People’s Anti-Offshore Committee itself, indicates that the movement has serious opposition potential and popular legitimacy.

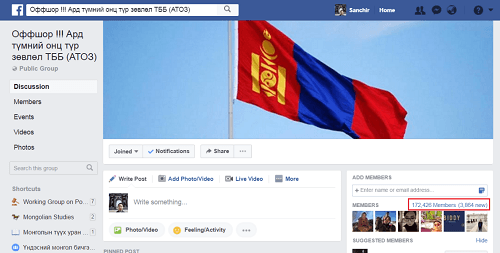

The Facebook group, ATOZ, one of the main anti-offshore movements, reached 172,426 members (not an insignificant number given Mongolia’s small population).

According to the Extended Fund Facility arrangement with the IMF, Mongolia has agreed to “cut spending, raise taxes and the retirement age, while pledging to maintain a flexible exchange rate and build a stronger regulatory environment for banking and finance.” This is in line with the standard IMF austerity package that has in other countries led to the shrinking of the national economy, which makes future debt repayments an even greater burden (Toussaint, 2010; Varoufakis, 2016; Weisbrot & Sandoval, 2007). For this reason, I have personally been involved in advocating that Mongolia carry out a debt restructuring process consistent with the United Nation’s principles along with a new Debt Sustainability Analysis, the partial writing-off of debt to manageable proportions, and a citizen debt audit to differentiate between odious and legitimate debt [2].

In my opinion, one of the reasons why getting assistance from either the IMF or China have become the normalized options for Mongolia is because neither would necessarily shake-up the whole system as it currently exists. These two options maintain the position of the dominant class while the current administration will not have to tackle the existing debt problem. They can just pass the buck onto the next government by extending and refinancing the loans. In short, it allows for a position that maintains the status quo rather than holding anyone to account for the current position Mongolia finds itself in.

[1]Leaks of offshore information from Mossack Fonseca, a law firm in Panama, exposed a lengthy list of potential tax evasion, money laundering, and illegal transactions, which involved top level government officials from a number of countries, including Mongolia. Among the 49 Mongolian individuals and business entities named in the Panama Papers, there were accounts related to two former prime ministers of Mongolia, S. Bayar and S. Batbold; parliament member S. Bayartsogt; and other government officials.

[2] For example, during my speeches at the Left Forum organized by Rosa Luxembourg Stiftung in March 2016, Asia Europe People’s Forum held in Ulaanbaatar in July 2016, and the Peoples Research Training in Mongolia organized by Asia Pacific Research Network (APRN), People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty (PCFS) and Centre for Human Rights and Development (CHRD).

References:

Toussaint, Eric. Debt, the IMF, and the World Bank: Sixty Questions, Sixty Answers. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010.

Varoufakis, Yanis. And the Weak Suffer What They Must?: Europe’s Crisis and America’s Economic Future. Washington, DC: Nation Books, 2016.

Weisbrot, Mark, and Sandoval, Luis. Argentina’s Economic Recovery: Policy Choices and Implications. New York: Center for Economic and Policy Research, October 2007, #2.

Close

Close