Our debt: 10 million sheep during the Manchu period, 400 million today!

By uczipm0, on 23 June 2016

The following blog post was written by H. Batsuuri. It develops an analogical analysis between Mongolia’s current economic situation and the late Qing and early revolutionary period, at the beginning of the twentieth century. The similarities lie in the foreign economic and political domination partnered with national rulers that plays an important role in increasing debt, exploitation, poverty, and prompted resistance leading to the revolution.

H. Batsuuri is a Mongolian economist who graduated from the London School of Economics, and is a founder and editor of a social and economic journal Shinjeech meaning ‘Analyst’. He is also an Advisory Board Member of the Emerging Subjects project. In the last couple of years, he has been actively researching, observing, engaging and commenting on Mongolia’s current economy, politics and social issues and has suggested various solutions.

He has published dozens of research and newspaper articles addressing topical debates surrounding the free market, neoliberalism, capitalism, democracy, governance, debt, tax, bank, offshore, trade, mining, sovereign bonds, investment, international politics and so on. He is a leading public well-known figure giving in-depth observations and expertise knowledge, and is currently running in the upcoming national parliamentary election as a candidate for the Independence and Unity Party.

In 1844, a Chinese merchant met the French traveller Évariste Régis Huc in Russia. What the merchant told him is noted in historical records: “We have the same business to eat up the Mongols, right? You eat them by your prayers, and me, by my trade and loan interests. We, the merchants devour them with their hair and skin. You don’t know the Mongols. Don’t you see? They’re all like children… The debt of the Mongols has no end. It is shifted from generation to generation. Oh, how great is this debt, it’s like the golden chest”.

What I learnt in history class in middle school as “The people made the revolution against the repression and exploitation of the internal and external greedy merchants, the rich and the aristocrats” has been engrained in my mind. To a 13 year old boy, the intensions of the external invaders was clear, but the reflections about the internal oppressors, and the reasons why Mongolians had to oppress each other has left many unanswered questions.

The 1911 National Revolution for Freedom and the 1921 People’s Revolution were both started to overthrow the foreign abuse and domestic repressive system – and they both reached their goals. At that time, the domestic and foreign oppressors worked hand in hand. Historical records show how some Mongolian traitors were bound up with the foreigners and closely cooperated on exploiting people and depleting national wealth.

Concerning the external debt of today’s Mongolia, the situation is very similar to that of the debt issues of 1911. When we look at the challenges around Tavan Tolgoi, the condition of Dubai contract deal for Oyu Tolgoi and the ever-increasing debts and loans, it seems like some of our decision-makers share the same life with the foreigners. One of the triggers of the 1911 Revolution was the foreign debt distress that Mongolians suffered from. At that time, Chinese merchants would bribe local chiefs and aristocrats to impose goods like tea, textile and other products that they brought from China to Mongolians with higher prices. In the case of goods loan, they would take interest that doubled or tripled the initial price. The merchants and pawnshop keepers would implement corrupt policy by conspiring with the local aristocrats and impose tough loan conditions and repayments. Even for their personal debts, the local aristocrats would act on behalf of the State and make people pay them.

For instance, a block of green tea, a product of high demand during that period, cost 0,8 lan (29,84 gr) silver piece. The merchants would lend a block of tea for 1 sheep (a sheep cost between 2 and3 lan or 74,6 gr-111,9 gr silver) and get a two-year old lamb for one-year-interest. If the debtor couldn’t repay his/her debt in a year, the lamb was calculated as a mother animal to give another lamb. This logic was applied in raw material trades like hide, leather and wool; so 2-3 sheepskin would be taken as an interest of one sheepskin.

As the Chinese merchants started keeping the part of the livestock (that they swindled from the Mongolian herders) in the pasturelands, the number of the Chinese men married with Mongolian women and herding livestock increased. Some merchants would hire poor Mongolian herders so-called “khuchnii khun” (man of labour) to raise their livestock. These merchants would pay nothing for their exploitation of the Mongolian pasturelands. At that time, the debt was categorized as “albany ör” (official debt) and “aminy ör” (personal/private debt). Both the official and private debts of aristocrats had to be paid by the common people. For the Chinese merchants, making contracts with the local authorities to supply them with great amount of loan for their personal and official use, and have their subordinate people pay these debts was a profitable and easy way to increase their wealth. In the debt solution order, the family and extended family of the debtor repay his/her debt in the case where he/she was not able to repay their debts; and the subordinate people paid the debt of the debtor who was deceased or disappeared. Chinese merchants Bayansan and Dalai mentioned their practice to solve their loan issues by bribe and corruption in the following way, “we get 10 lan for 5 lan and 20 for 10. We submit some part of the extra profit to the authority”.

Some rich Mongolians and aristocrats who sold the country had their own house and land in Beijing. This is similar to today’s political situation where certain decision-makers’ offshore accounts and real estate properties are located abroad. The Chinese merchants would try to keep the initial debt as the source of income by only collecting its interest. Besides, they would run a policy to get the raw materials and wealth of the Mongols with an extremely low price, or even for free.

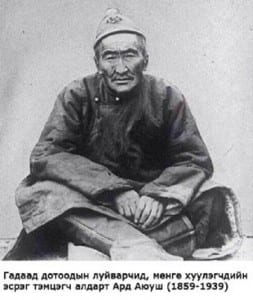

The issues around the external debt, the conspiracy of the foreign and domestic exploiters, their oppression and corruptions that are recorded in the history, aren’t they familiar to you? To me, they’re too familiar. The Ard Ayush (Ayush The Folk) movement, known as the “Tsetseg Nuuryn Duguilan” (The Flower Lake Circle) in history, was actually a resistance against the external debt distress and the double abuse by the corrupted county chief Manibadar and the Chinese greedy merchants.

Figure 2. Ayush The Folk, the leader of the civil movement against the foreign and domestic exploiters

The records show that in 1911, the total amount of Mongolia’s external debt reached to 30 million lan of silver. If we suppose the price of a sheep for 3 lan silver, we must have had a debt of 10 million sheep at that time. As for today, our external debt is counted at least 24 billion USD. If we calculate one sheep for 60 USD or 120 million tögrögs, it means that we have a debt of around 400 million sheep. But we have only 55 million livestock, in which is numbered 24 million sheep. So we actually live inside a period of debt that is 40 times more than that of the Manchu-domination period. When we look at the expense of 4,5 USD for each income of 1 USD in our economy, it’s clear for the debt to be inevitable. One can naturally wonder what kind of distorted system and whose policy is running here…

When we look at the current socio-economic situation in Mongolia, we could summarize that it is under the same conditions that shaped the Chinese merchant’s exclamation “The debt of the Mongols has no end. It is shifted from generation to generation. Oh, how great is this debt!” that was said more than 170 years ago. Our ancestors resisted the injustice, stealth and repression made by the corrupted domestic and foreign oppressors. They burnt down the debt orders and liberated themselves and their future generations from the internal and external exploitation. But what about us? We shouldn’t leave debt to our children; we don’t have the right to darken their future. We must not accept the open and hidden oppression and swindling. We do have the choice and it’s already the time to make the right choice. The time has come to elect those who know the problems and propose solutions, those who have a clean reputation.

Bibliography

Б.Уламбаяр. МУИС. Түүхийн эрхлэгч Undated Гадаад болон дотоод худалдааны түүхэн тойм, алба татварын тухай, accessed May 2016.

Close

Close