Unlocking collective trauma: Knowledge production, possession, and epistemic justice in “The Act of Killing” and the 1965 genocide in Indonesia

By Dana Sousa-Limbu, on 20 September 2023

A blog written by Kafi Khaibar Lubis, 2022-23 student of the Environment and Sustainable Development MSc

“Your acting was great. But stop crying.”

Not more than 20 years ago, I was called by my hysterical mom to quickly get inside the house while playing outside as a sunburnt pre-teenager. She was upset like I had never seen before, locked the doors, and shouted things at me, my dad, my uncle, and everyone in my family. She cried. I was just wearing a normal-sized T-shirt gifted by my beloved uncle, the only sibling my mother had. I never understood why it upset her so much until decades later.

Chapter 1: Sickle and Hammer

A couple of months ago, I crashed into a screening held by a film society at one of University College London’s neighbouring universities. It was for a film that I had always wanted to see but was never able to: “The Act of Killing”, or “Jagal” in Indonesian (literal English translation: “slaughter”), a documentary by Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn, and an anonymous Indonesian co-director. It was about the mass murder that happened in Indonesia around 1965-1966 to millions of people associated, or assumed to be associated with, the Indonesian Communist Party.

This film was never formally distributed in Indonesia. It was only known through underground screenings and word of mouth, which was not a surprise since the topic of the 1965 mass murder itself is very hard to talk about in the country. One could risk being distanced from, labelled a communist (pejorative), or even prosecuted. The film, therefore, plays a significant role in opening and normalizing discussions about the topic and taking a step in unlocking what has been, for so many decades, a painfully silenced collective trauma.

Chapter 2: Confrontation with Reality, Truth, and Knowledge

At the beginning of the screening, they invited Soe Tjen Marching, writer of the 2017 book titled “The End of Silence: Accounts of the 1965 Genocide in Indonesia” to give an introduction. Her father would have been a victim of the mass murder, if it had not been for the delay in processing his name to join the party’s organizing committee. She introduced the film by bringing to light recently declassified documents from the government of the United States of America that played a significant role in setting off the chain of events that led to the 1965 mass murder. However unsettling, the documents act as robust evidence against justifications made for the mass murder, including and especially the government-produced film of the event that was once a mandatory watch for schoolchildren in Indonesia in the 1980-1990s. These forms of knowledge possession have perpetuated the exclusion, silencing, and denial of genocide, leaving the victims at the hand of many types of injustice (Oranli, 2018; Oranlı, 2021).

“The Act of Killing”, on the other hand, used a unique approach to documentary filmmaking that allowed the perpetrators to participate in the production process and shape the story themselves. The film asks former commanders of the Indonesian death squads, who oversaw the execution of hundreds of thousands of suspected communists and other political dissidents in the 1960s, to recreate their atrocities. Devoid of remorse, the perpetrators were proud of their actions, even providing creative choices to narrate the reenactment in the style of their favourite Hollywood genre: action western.

The film’s epistemology is based on the belief that by allowing the subjects to participate in the production process and control the narrative, the film can achieve a level of authenticity and emotional depth that traditional documentaries may not be able to achieve. One might question why after decades of silencing and exclusion, a filmmaker would give a platform to the perpetrators. They are, after all, most often indifferent to the injury they have done and lack any understanding of the extent of harm they have caused. But as the film progressed, it was clear that this was a well-calculated strategy. It was precisely by giving space for the perpetrator to show off their crime that the truth became plain and visible, the genocide clear and undeniable.

Figure 1. Herman, one of the perpetrators, comforting his daughter, Febby, while she is crying in the aftermath of shooting a scene re-enacting the terror towards families of the 1965 mass murder victims (Oppenheimer, 2012).

There was one powerful scene in which the daughter of one of the perpetrators could not stop crying after they shot a reenactment of women and kids being taken away from their homes and their houses set on fire (Fig. 1). She was just an actress, playing one of the kids in the scene. The perpetrator was visibly aware of his daughter’s distress and was trying to comfort her: “Your acting was great,” he said, “but stop crying.” It was followed by depictions of other actors, children, and adults alike, looking traumatized by the reenactment, some requiring physical assistance to calm them down and remove themselves from the situation. Although obviously much milder than what truly happened in the 1960s, the activity incited an exchange of knowledge, blurring the reality and fiction of what they wanted to portray. It was no hidden knowledge that their crime caused significant terror; it was simply something that everybody was afraid to say. Now, by loudly narrating their own ruthless crimes, the perpetrators got a taste of their own medicine.

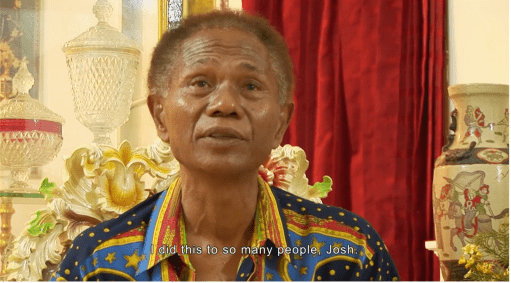

This method of filmmaking provides an interesting basis for analysis of epistemic injustice, delving into the nature and limits of knowledge. By allowing the perpetrators to narrate the story, the film not only exposes society’s normalization of celebrating brutal murderers but also places the killers in the position to confront their own past actions and their consequences. Another interesting example was Anwar Congo, a prominent leader in the death squad. Throughout the film’s first half, Congo seemed unrepentant and rather laid-back while recounting the murderous event. However, as the cowboy style film he had directed about his killing past neared its end, he started feeling nauseous. He cried, seemingly having an extremely late epiphany (Fig. 2). In that scene, a vivid connection is built between having knowledge and being aware of one’s own actions.

Figure 2. Congo showed regret near the end of the film. “Did all the people I killed feel what I felt in that scene?” Joshua responded, “Actually, the people you tortured and killed felt far worse because you knew it was only a film. They knew they were being killed.” (Oppenheimer, 2012)

The fact that the filmmakers tried more than 30 times to find and interview different subjects is, in some ways, an attempt to understand the many forms of knowledge and the chase of finding the hidden knowledge held by an individual, as categorized in the Johari window (Bhakta et al., 2019; Shenton, 2007). Also, such effort was a sign that the film was not about them or the filmmaking. Oppenheimer had his realization moment and shifted the focus to the perpetrators; that what they did, was almost like a multi-layer fiction, a simulacrum, to say the least, of hidden knowledge, unknown knowledge, and blind knowledge of the genocides, their regrets, and their pride that in itself is a hidden remorse trying to justify their past actions.

Reflexivity and self-awareness become the central theme in the film’s method of unveiling the truth about the tragic past. With the denialism of the perpetrators that have been observed elsewhere, the creators might or might not be intentionally utilizing this reflexive participation measure to disclose objective information and even to induce empathy in people who were detached from their cruelty. With the surfacing of the declassified government documents, the fear and secrecy of the victims, and the genocide denialism, the injustice of knowledge possession has been hiding in plain sight, crossing identities and the reality of a whole nation.

Chapter 3: Empathy, Trauma, and Dreams of Justices

The images of my memories started to become clearer. I understand better about that day, the day my mother was upset beyond measure towards everyone. I remember the T-shirt I wore, which my uncle gave to me. It was a dark blue T-shirt with a sickle and hammer logo and the bold black writing of “SOVIET UNION”.

The discourse on epistemic justice and participatory measures extends beyond academia and into fieldwork, practice, and lived experience. My own family had their own trauma regarding the 1965 mass murder, which I never entirely understood since it could never be talked about openly. “The Act of Killing” tried to unveil the chronic terror of the tragedy both loudly and delicately, borrowing the voice of the perpetrator to raise the volume of the victims’ collective voice. The film confronted the perpetrators not with a team of obvious enemies, but with the most powerful confronter of all: a mirror image of themselves.

The fruit of participation, or engaging people, can open and lead to many kinds of knowledge, whichever type and however vile or inspirational that is, that leads to something minuscule such as being free to wear anything we want, to be anything we want, to justice, and the truth. Moreover, the disclosure of information, whether it be from the state to the people, from the victims to the public, or even from the very perpetrators to their own eyes and mind, can be the first step to opening up a complex dialogue, taking responsibility and addressing a proper apology, healing a collective trauma, and marching towards a better, more empathetic and just future.

References

Bhakta, A., Fisher, J., & Reed, B. (2019). Unveiling hidden knowledge: Discovering the hygiene needs of perimenopausal women. International Development Planning Review, 41(2), 149–171.

Oppenheimer, J., Anonymous, & Cynn, C. (2012). The Act of Killing. Drafthouse Films

Oranli, I. (2018). Genocide Denial: A Form of Evil or a Type of Epistemic Injustice? European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 4(2), 45–51.

Oranlı, I. (2021). Epistemic Injustice from Afar: Rethinking the Denial of Armenian Genocide. Social Epistemology, 35(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2020.1839593

Shenton, A. K. (2007). Viewing information needs through a Johari Window. Reference Services Review.

Close

Close