How Research Creates More Inclusive Spaces: Bar Elias, Lebanon

By h.baumann, on 12 November 2019

Co-authored by Joana Dabaj

Originally published by UCL Institute for Global Prosperity

It is not every day that academics plant trees, paint pavements, or install park benches. But that is exactly what I, and other researchers from the Institute for Global Prosperity (IGP) and other parts of UCL, did when we recently completed a project in Bar Elias, a refugee-hosting town in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

Our project was a long-term collaborative engagement with local residents that resulted in tangible changes to the local urban fabric. Along the main road at the entrance to the town, we enhanced pedestrian safety, mobility and accessibility for all, created child friendly spaces suitable for gathering and sitting in the shade, and rehabilitated a dilapidated public park. Based on participatory research with the community, this “spatial intervention” aimed to address problems articulated by Lebanese residents as well as Palestinian and Syrian refugees, found in their urban space.

A Town Transformed

Located half way between Beirut and Damascus, and only 15 km from the Syrian border, Bar Elias has been transformed by the influx of Syrian refugees – gradually turning it from an agricultural village into a city. In addition to increased construction inside the town’s urbanising space, over one hundred informal tented settlements now dot the outskirts of the city. Tensions have increased since the number of refugees has risen to the point that they outnumber local residents. But on the other hand, international aid has started to bring several positive changes too, with a hospital, a dispensary and a new solid waste sorting and treatment plant, built in recent years.

Our partner, London-based, non-profit design studio CatalyticAction, has been implementing participatory projects enhancing community cohesion in the Beqaa for over four years. Their long-standing engagement with the community and the trust they had already built with local actors and the municipality was a key asset in making this project happen, especially in the relatively short project time frame of 23 months. It allowed them to bring on board all relevant local actors and negotiate successfully between them.

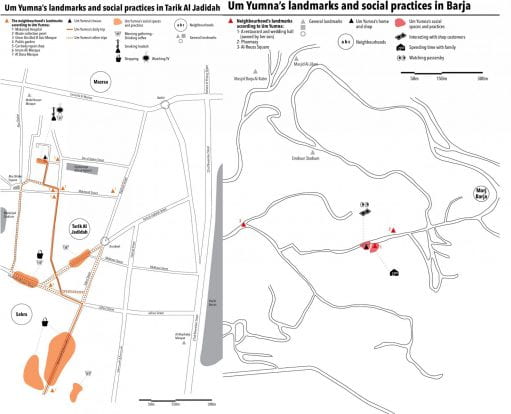

One of the first things CatalyticAction did in this project was recruit a team of highly motivated Citizen Scientists from the Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian communities of Bar Elias. These local researchers in Bar Elias were trained in basic spatial and social science research methods as well as research ethics (skills they first applied during the Development Planning Unit’s SummerLab in 2018 – a workshop in Bar Elias, 2018 – which focused on questions of public space in the town).

The second phase of our work with Citizen Scientists was a participatory workshop on the links between infrastructure and vulnerability conducted in October 2018. The participants, who ranged from age 18 to 69 and represented all nationalities living in Bar Elias, learned and applied research methods including participatory mapping, semi-structured interviews, and street observation in order to analyse the infrastructural challenges of the town and propose ways of addressing them.

Following the workshop, CatalyticAction gave participants’ ideas shape by translating them into a specific design. In December, the draft design was presented to participants and the public for another round of feedback. CatalyticAction also presented the findings and proposals to the Bar Elias municipality and negotiated conditions of implementation that took their existing plans into account. For instance, the municipality had planned to turn the dilapidated public space behind the hospital into a parking lot. At the same time, the revitalisation of this neglected area was a key aspect of the workshop participants’ vision for a city centre that was safe, welcoming and inclusive. By devising a new design in which only a smaller portion of the area was turned into parking space, we were able to reach a compromise that worked for everyone.

Implementation

After a long and wet winter in Lebanon, which did not permit construction work, the implementation took place in May 2019 along the road from the Clock Tower marking Bar Elias’ central square to the main road’s intersection with the Beirut-Damascus Highway.

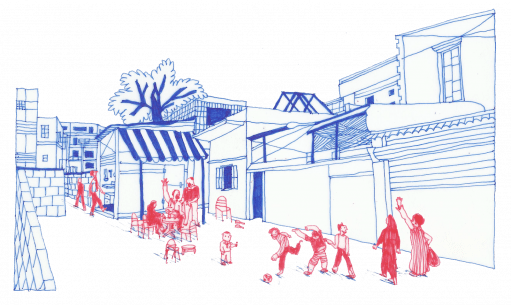

Public spaces for gathering: A large circular seating area was built on a wide pavement next to the medical dispensary, where patients often wait for their appointment but do not have shade or benches. To change this, we discouraged cars from parking on the pavement through the removal of ramps and the creation of parking spaces behind the dispensary. To create sufficient shade, we installed a metal screen to cover the seating area. We laser-cut the aluminium panels in such a way that the shadows created spells our phrases highlighted as important by the local researchers and the community members who participated in the October workshop. They showcase values and hopes for Bar Elias such as “Bar Elias – the mother of strangers, cleanliness and togetherness”. While the benches themselves are made of concrete, and involve play elements for children, they are also covered in colourful mosaics made by two artists – sisters Nour and Amani Al-Kawas, whose mother is from Bar Elias. These were made from leftover ceramic tiles collected at a local tile shop. Beyond this main seating area, several blocks for resting were added along the road together with smaller shades. In addition, we planted trees creating much-needed shade for pedestrians and shopkeepers, as well as shades made of recycled materials.

Accessibility and safety: The sidewalk along the Bar Elias main road is up to 60cm high in some places, making it very difficult to navigate. Because of this, and because cars often park on the pavement, many pedestrians walk on the road, exposing themselves to speeding cars. In order to facilitate better access – especially for the elderly, those with mobility impairments, and parents pushing strollers – we put in place a total of 15 pedestrian ramps onto the pavements.

In addition, we installed three speed humps in key locations of this area used by many pedestrians throughout the day. The location of the speed humps was agreed together with the municipality. To encourage children to use the sidewalks, we painted floor games along the sidewalks, adding colours and playfulness. Along the road, street signs were added to locate important areas: showing the Dayaa’ / town centre, the taxi stand with its new benches, the rehabilitated public park, as a sign marking the main shaded seating area, which we named Dar or Abode. We also installed spotlights overlooking the Dar and the public garden.

Rehabilitated park: A public green space just off the main road that had once served as an important public space for the town had fallen into disrepair with the construction of the hospital and the new medical dispensary. We organised a collective clean-up session to free the area of rubbish and hired gardeners to remove the overgrowth, revealing some beautiful trees and bushes. Then we planted additional trees including an olive tree, and plants including rosemary. Together with the Citizen Scientists, we also installed three wooden benches, which were painted in collaboration with children and made at a local carpenter’s shop.

To mark the entrance to the newly-revitalised park, a Jasmine arch was installed along the main road and a pathway was paved to make it accessible. This way, users of the hospital and medical dispensary as well as visitors and staff will be able to easily recognise a space they can use to relax and gather, shielded from the traffic and noise of the main road. While passers-by interviewed by Citizen Scientists about their expectations expressed concerns about the maintenance of the rehabilitated green space, the municipality has already agreed to take responsibility for its upkeep. During construction, the municipality of Bar Elias had already shown its support for this work, sending trucks and workers to remove the rubbish and water new plants. Two weeks after the space was inaugurated, the municipality also built a water well for the park. Employees of the medical dispensary were so happy with the new benches and path that they expanded the intervention themselves to include additional benches and planters along the new path.

During the implementation of this project, different community activities took place. For example, collecting and reusing plastics to form the smaller shade structures, painting the benches and painting a mural. The mural, in collaboration with The Chain Effect, an initiative aiming to encourage cycling in Lebanon, transformed a previously rough wall into a colourful wall at the entrance of the road. The spatial intervention was inaugurated on a busy Ramadan evening through an interactive performance by The Flying Seagull Project , near the main seating area where children and parents joined in for a fun and memorable night.

Knowledge transfer: An important aspect of the intervention was the joint learning, as well as sharing skills. The intervention has built the capacity of the Citizen Scientists and other residents to analyse problems, has encouraged other members of the community to participate in this work, think about diverse identities, and negotiate collective solutions. This project has led to the creation of a social infrastructure which is a public good for the entire city. There are also examples of local members of the community using this project to share knowledge elsewhere. One local Syrian researcher who worked as a school teacher in Bar Elias before moving back to her hometown in Syria implemented workshops with Syrian students at a local school. The children learned about the importance of recycling, reusing and taking care of the environment. Through discussion and arts and craft, they learned how to make a beautiful tree out of plastic and other discarded material. They also reflected on uses of the streets and how they would like to change them.

Next Steps

Now that the spatial intervention is complete, we will focus on monitoring its impact on the way Bar Elias residents turn this public area into a social space. Over the coming months, they will monitor the usage of the new spaces at regular intervals. This will allow us to track the impact of the participatory spatial intervention and make adjustments in the future if necessary.

Currently, a project funded by UCL’s Grand Challenges programme on Migration & Displacement is enabling the Citizen Scientists to further develop their skills. Through a partnership with CatalyticAction and Salam Ya Sham, an arts organisation founded by Syrian refugees, local researchers are learning to use film-making as a research tool. They are now in the process of making several short films about the infrastructural challenges facing Bar Elias.

(c) Salam Ya Sham – Citizen Scientist Moayad Hamdallah filming at the Bar Elias waste sorting plant, July 2019

In addition to ensuring maintenance through the municipality and other actors, CatalyticAction have also been in discussion with a local NGO about working together on further development of the public space and its activation. Thus, although the British Academy-funded project ends this month, our ongoing engagement with the town – and especially the Citizen Scientists we’ve worked with for close to a year now – will be enabled through the RELIEF Centre, whose Vital City research stream will also trial small-scale spatial projects to pilot urban improvements for both refugees and hosts.

Further Reading:

Find out more about the participatory research process that led to this intervention: Collaborative team from IGP and DPU facilitate a participatory spatial intervention in Lebanon, 8 January 2019, Institute for Global Prosperity, UCL

A blog by Professor Caroline Knowles, the Director of the British Academy’s Cities & Infrastructure programme about witnessing the participatory spatial intervention in Bar Elias: Creating Inclusive Urban Space in Lebanon, 2 June 2019, Medium

A blog about our recent concluding symposium: Blog: Symposium – Vulnerability, Infrastructure and Displacement, 5 July 2019, Institute for Global Prosperity, UCL

To learn more about the IGP’s work with Citizen Scientists:

What is Citizen Science? London Prosperity Board

Launching a Citizen-Led Prosperity Index, Bartlett 100

IGP-led team wins funding for Citizen Science project exploring local botanic knowledge in Kenya, 29 January 2019, Institute for Global Prosperity, UCL

Close

Close