‘Portland House’: Robert Adam’s unexecuted designs for the Duke of Portland’s London residence

By the Survey of London, on 7 April 2017

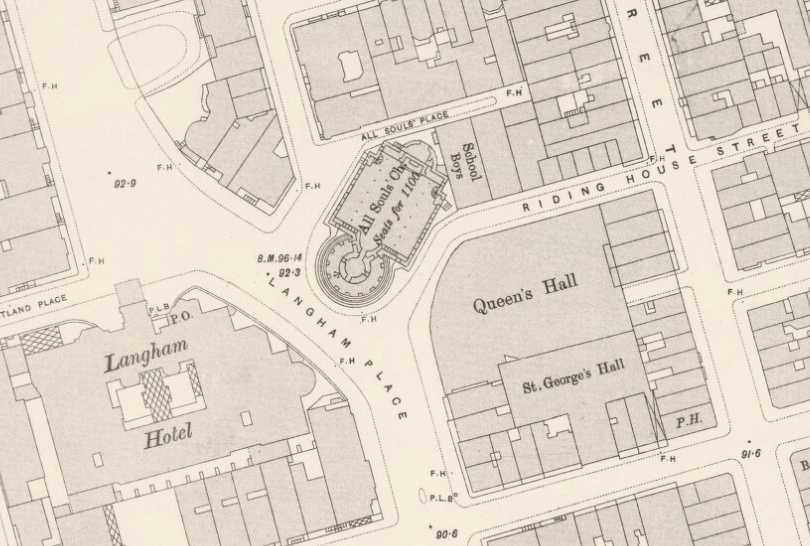

The Adam brothers’ celebrated street improvements at Mansfield Street and Portland Place, carried out from the 1760s on the Marylebone estate of the Dukes of Portland, are among the many significant buildings covered by the Survey of London’s forthcoming volumes on South-East Marylebone. Less well-known, however, is the detached mansion that Robert Adam designed around 1770–2 as a new London residence for the 3rd Duke, to stand on a large site on New Cavendish Street, looking down Mansfield Street. Though it was never built, its story can be pieced together from designs in the collection of Adam office drawings at Sir John Soane’s Museum – the principal resource today for anyone wishing to study the work of the Adam brothers.

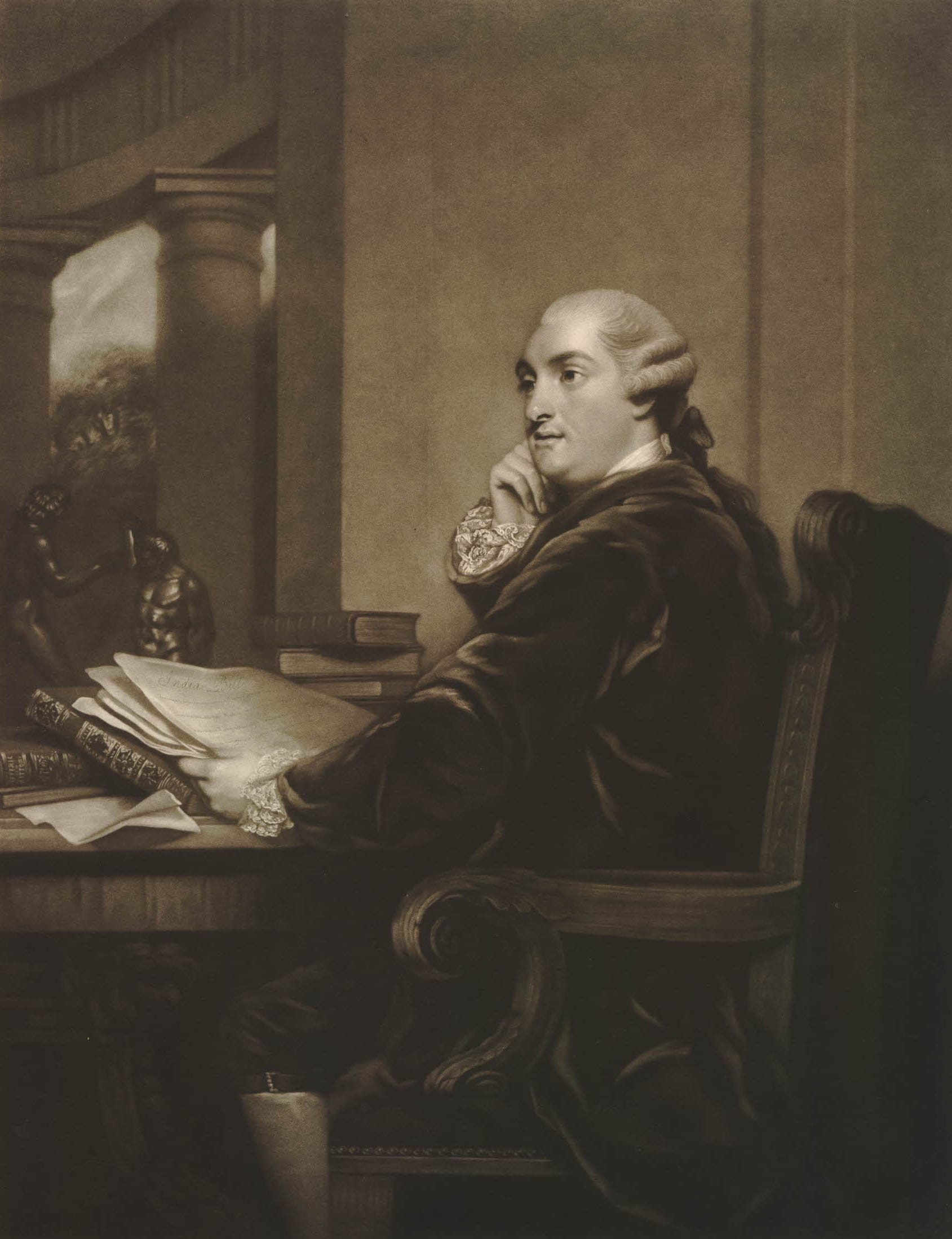

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland. An engraving of 1785 after Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of the Duke. British Museum, Prints & Drawings Dept (museum no. 1902,1011.3545) © Trustees of the British Museum

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland (1738–1809), had recently married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, daughter of the 4th Duke of Devonshire, and was already embarked upon a career as a statesman that would see him appointed 1st Lord of the Treasury (the equivalent of today’s prime minister) on two occasions, in 1783 and 1807–9. But although he had succeeded to his father’s title in 1762, the 3rd Duke did not immediately inherit all his estates. By the terms of his father’s and grandmother’s wills, the Duke’s mother, Lady Margaret Cavendish-Harley Bentinck, the Dowager Duchess (1715–85), retained a life interest in the family’s lucrative Cavendish lands, and she also held on to her husband’s house in Whitehall – leaving her son short of funds and without a London residence. The situation was exacerbated by strained relations between the two. They argued over country seats, in the end engineering a ‘house swap’ (she favoured Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire, he preferred Welbeck, Nottinghamshire), and failed to see eye to eye on politics as well as family finances. The Duke was a Rockingham Whig, intent on curbing what he perceived to be an increase in royal powers under George III; she numbered the king and queen among her friends, and was especially close to John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, the royal favourite and prime minister in 1762–3, a man whom her son vehemently distrusted. The Duke complained to anyone who would listen that he was required to pay rent for a London house when he should have had access to the ducal residence in Whitehall. And so a new, Adam-designed townhouse at the head of Mansfield Street would suit his intended station as a leading politician and also act as a focus for his fast-improving Marylebone estate.

Portrait busts of William Bentinck, 2nd Duke of Portland, at centre, his wife Lady Margaret Cavendish-Harley at left, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu at right, in ovals, with coats of arms below, allegorical objects between, curtains at left and above, in ornamental frame. From a drawing by Vertue after a painting by Zincke, 1739. British Museum, Prints & Drawings Dept (museum no. 1849,1031.70), © Trustees of the British Museum

In its size and scale the house that Adam designed, intended to be known as Portland House, was more like a country pile than a townhouse. In this and in certain elements of its internal planning it shared similarities with Lansdowne House, Adam’s first big private London commission, designed initially for Lord Bute but finished after his fall from favour in 1763 for his rival, another future prime minister, William Petty Fitzmaurice (1737–1805), 2nd Earl of Shelburne, later Marquess of Lansdowne.

Adam’s designs for Portland House were for a rectangular, two-storey block set within extensive grounds, with a garden to the rear and an entrance courtyard in front. The house itself would have been a fairly standard neo-Palladian affair, with seven central bays recessed behind projecting three-bay end wings. The entrance front was marked by a central portico with columns of what look like Adam’s favourite ‘Spalatro’ order – an invention of his own, based on a late-Roman capital he had seen in the Peristyle of the Emperor Diocletian’s Palace at Spalato on the Dalmatian coast (now Split, Croatia).

‘Principal Front of a House for His Grace the Duke of Portland’. Adam office elevation of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/2. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

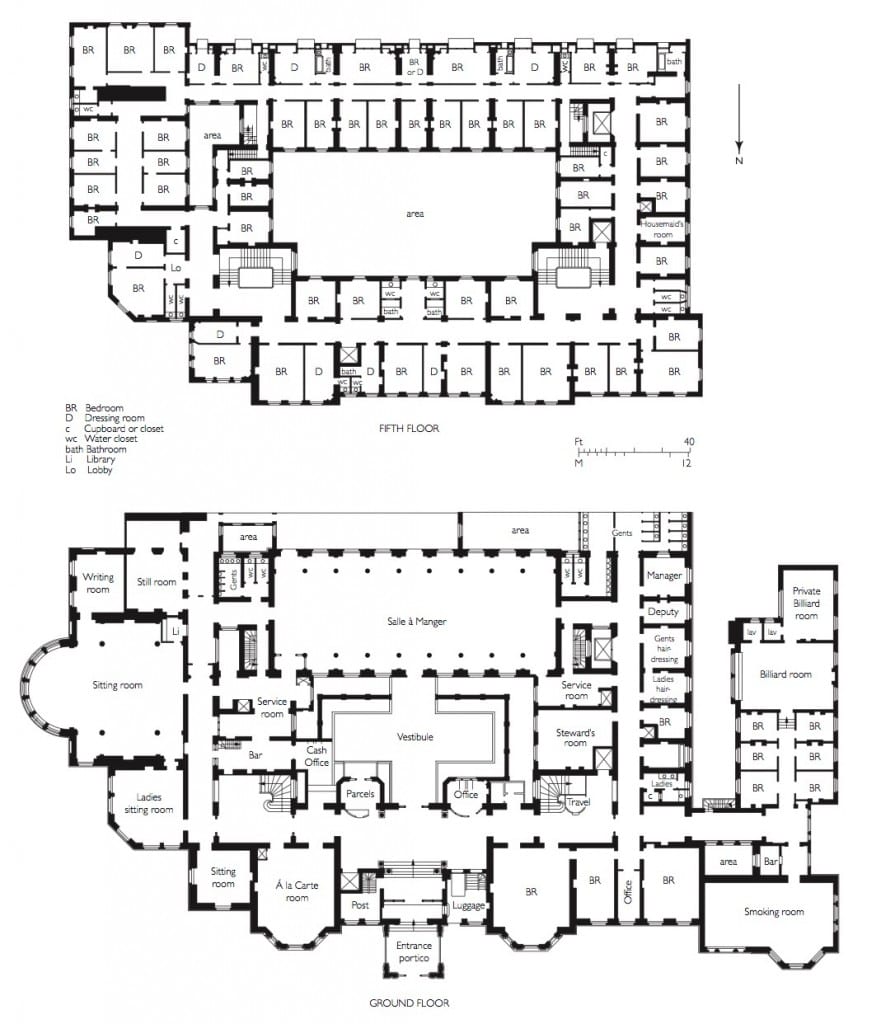

Portland House was to have had a lower ground floor given over mostly to servants’ rooms and storage, but with a gentleman’s library in a bowed room at the rear, and a bedchamber for the Duke and ‘Book room’ alongside. The principal state rooms were placed centrally on the floor above, with dressing rooms for the Duke and Duchess to either side. These connected with the little single-storey bays shown in shadow at each side of the mansion in the elevation, where there were to be powdering and retiring rooms, privies and water closets. There would have been further rooms on the first floor and in an attic within the hipped roof.

One of a pair of Adam office plans shows a proposed design for the house’s lower ground floor, with a rectangular courtyard in front, lined with coach-houses and stables on one side, kitchens, sculleries and more service buildings on the other. This plan matches the elevation, and shows how the portico served as a porte-cochère, with a curved ramp for coaches leading up to the main entrance. Also, in this plan an entrance screen wall and gateway is set quite a way back from the road, with more stabling and coach-houses in front.

‘Plan of the Ground Story of a House for His Grace the Duke of Portland’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/4. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

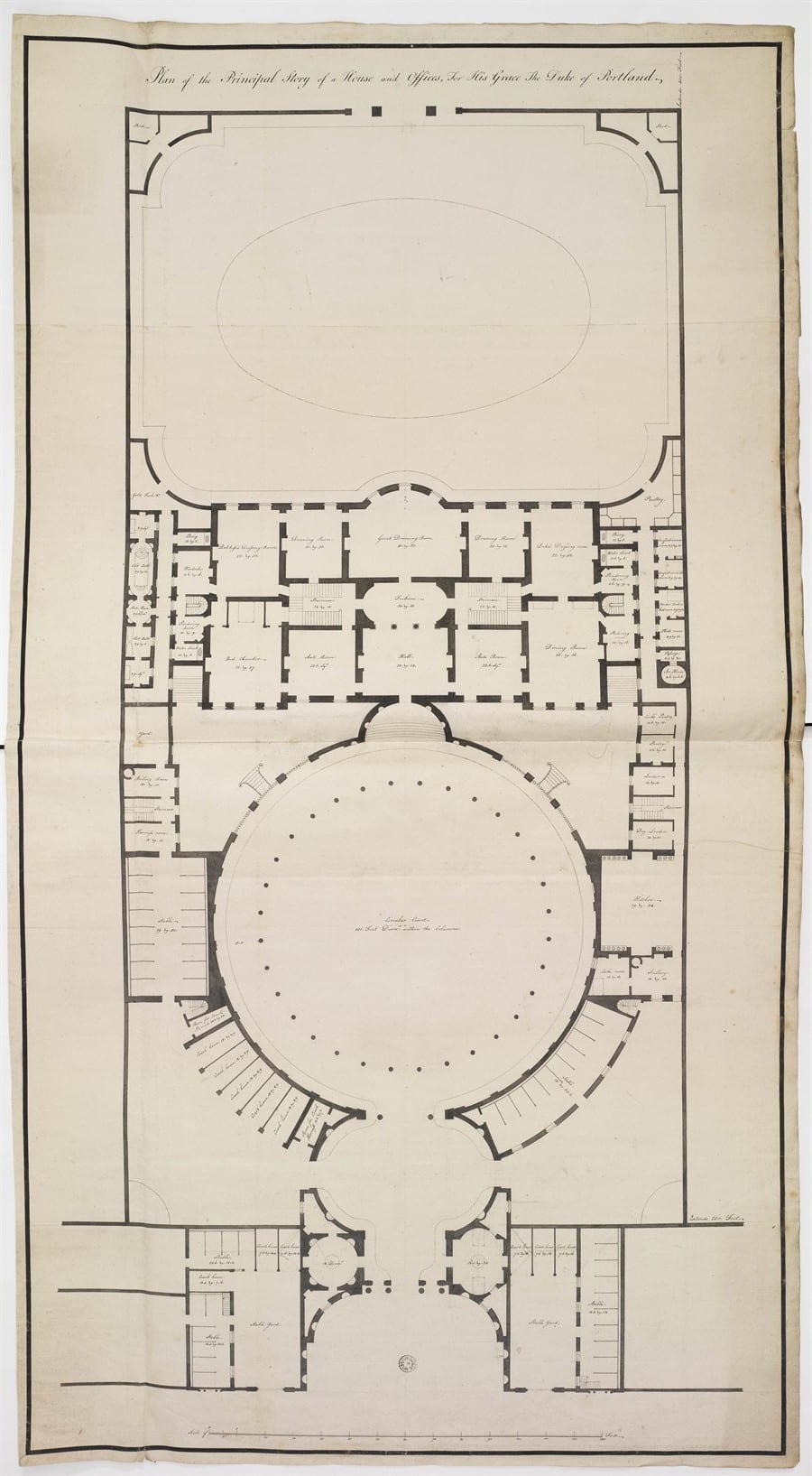

A first-floor plan offers an alternative arrangement, for a far more dramatic circular courtyard, surrounded by a roofed and colonnaded walkway. An accompanying section shows how this colonnade connected directly to the house, dispensing with the portico. This arrangement required further alterations to the design of the house, with windows at a higher level on the piano nobile, to allow light to enter the main rooms above the courtyard structure. Apparently this was the design chosen by the Duke.

‘Plan of the Principal Story of a House and Offices, For His Grace The Duke of Portland’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/5. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

‘Section through The Gateway, Circular Court and Body of the House, For His Grace The Duke of Portland, Fronting Mansfield Street’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/3. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

The Adams had been experimenting with colonnaded courtyards in house designs since the 1750s. Although their prime inspiration was always Italy, and in particular ancient Rome, there is a heavy debt to French plan-types, particularly Parisian hôtels, in their mansion schemes of the early 1760s. An unexecuted house of c.1764, intended for Lord Shelburne near Hyde Park Corner, was set behind a large front court, as was another design of the same date for a house for Lord Holland at The Albany, Piccadilly. Also, an early Adam brothers’ plan of around 1767 for the house they built for General Robert Clerk at the south end of Mansfield Street, facing Duchess Street, had the lower part of the house arranged in a curve and fronted by a semicircle of columns forming a carriage-way, in a similar manner to Portland House.

‘Gateway for Portland House’, Adam office design of c. 1770–2. This worked-up office version, with doors in the centre of the curved linking walls rather than windows, probably matches the rectangular courtyard plan for the house as shown in the ground-floor plan reproduced above. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/6. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

Other surviving drawings include an office elevation of a screen wall and gateway to stand on New Cavendish Street in front of the courtyard, in the form of a triumphal arch, closing the vista up Mansfield Street. A second version, in pen and pencil, apparently in Robert Adam’s own hand, has detailed measurements added to it, in preparation for drawing up estimates.

Design for a gateway for Portland House. This rendition in pen and pencil, in Robert Adam’s own hand, has had measurements added to help with working out an estimated cost, as mentioned in Robert Adam’s letter of February 1772 to the Duke, quoted above. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 51/98. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

As the Duke was both short of funds and overindulgent in his spending, a house on such a scale was evidently beyond his means. Unfortunately, the scheme also coincided with a reversal in the Adam family’s own fortunes, brought on by their attempts to develop the Adelphi and Portland Place at the same time. The Portland House project was still in hand in February 1772, when Robert Adam wrote to the Duke with a price for the ‘great gate’, porter’s lodges and some of the circular walls, and he sounded hopeful of further progress:

as Your Grace was so good as say, you would do every thing that should be necessary, to finish the end of the street, towards Your Grace’s House. I have therefore got an Estimate made of the great gate & porter’s lodges, with the circular walls that form the Entrance, & now take the liberty to send it enclosed, that Your Grace may consider it & if approved of, it will be of great Service, both to your Grace’s estate & to us, to be allowed to proceed with it this Season. [1]

But within a year the project had been dropped and the Duke was happy to let part of the site to the builder–developer John White for houses on the east side of Harley Street. The ground fronting New Cavendish Street was then leased by the Duke and the Adams to the architect-builder John Johnson, who erected the present Nos 61–63 there in 1775–6 (these will be the subject of a future blog post).

For a time around 1773–4 the Adams seem to have considered re-siting their ‘hotel’ for the Duke of Portland to the west side of Portland Place, where they had been planning at least two other very large aristocratic houses, for the Dukes of Kerry and Findlater, but this plan also failed to materialize, and the Duke of Portland when in London continued to live mostly at Burlington House, courtesy of the Duke of Devonshire. In 1807, when he was made 1st Lord of the Treasury for the second time, the Duke moved to 10 Downing Street, which was then as now the official residence of the 1st Lord of the Treasury (not the prime minister, though in modern times the same person has usually occupied both posts).

The Adams must have remained on reasonably friendly terms with the Duke, as they were allowed to continue to work on Portland Place, even though its completion was delayed until the 1790s by unfavourable economic conditions and the Adam brothers’ own financial problems; by then both Robert and James Adam were dead. Their cause may have been aided by the Duke’s friendship with their nephew, the Rt Hon William Adam of Blair Adam, the son of Robert and James’s older brother John Adam. A lawyer and advocate by training, and later a judge, he was one of the 3rd Duke’s great allies in the Whig party when it came to boosting party morale and raising funds in preparations for the general election of 1790.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks are due to Dr Frances Sands, Curator of Drawings at Sir John Soane’s Museum, for supplying the images of the Adam designs for the Duke of Portland’s house; these are reproduced here by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum. The catalogue entries for these drawings in the Adam office collection at the Soane can be found by following this link. A discussion of the designs also features in Fran’s book Robert Adam’s London, published to accompany the exhibition of that name recently held at the museum. See here for further details.

Reference

1. University of Nottingham, MSS and Special Collections, PwF 35

Close

Close

![The Langham Hotel (by The Langham, London, reproduced with a Creative Commons licence via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)])](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/files/2016/03/Langham-Wikipedia-Commons.jpg)