St Peter’s, Vere Street

By the Survey of London, on 15 January 2016

The small brick church that is St Peter’s, Vere Street, stands just north of Oxford Street, tucked away behind department stores, as inconspicuous as its larger sibling, St Martin-in-the-Fields, is prominent. This modest place of worship was built in 1721–4 as the Oxford Chapel, a private undertaking for the 2nd Earl of Oxford and Mortimer, Edward Harley, who, through marriage to Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles, had inherited extensive lands north of Oxford Street that were then just beginning to see building development. The architect of the estate chapel was James Gibbs, otherwise associated with the Harley family, and resident across what was then Henrietta Street (now Place) in a new house of his own devising from 1732.

St Peter’s, Vere Street, from the north-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

The interior of the chapel, while indebted to Christopher Wren for its basic forms, was in its particulars what John Summerson termed a ‘miniature forecast’ of St Martin’s. [1] Corinthian arcades carry an elliptical nave vault to cross-vaulted aisles, and once private galleries overlook the chancel. In 1734 Edward and Henrietta’s only child, Lady Margaret Harley, married the 2nd Duke of Portland in the chapel. From that marriage the valuable landed estate descended to and took its name from subsequent Dukes of Portland, later passing to Lord Howard de Walden.

The chancel from the south-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

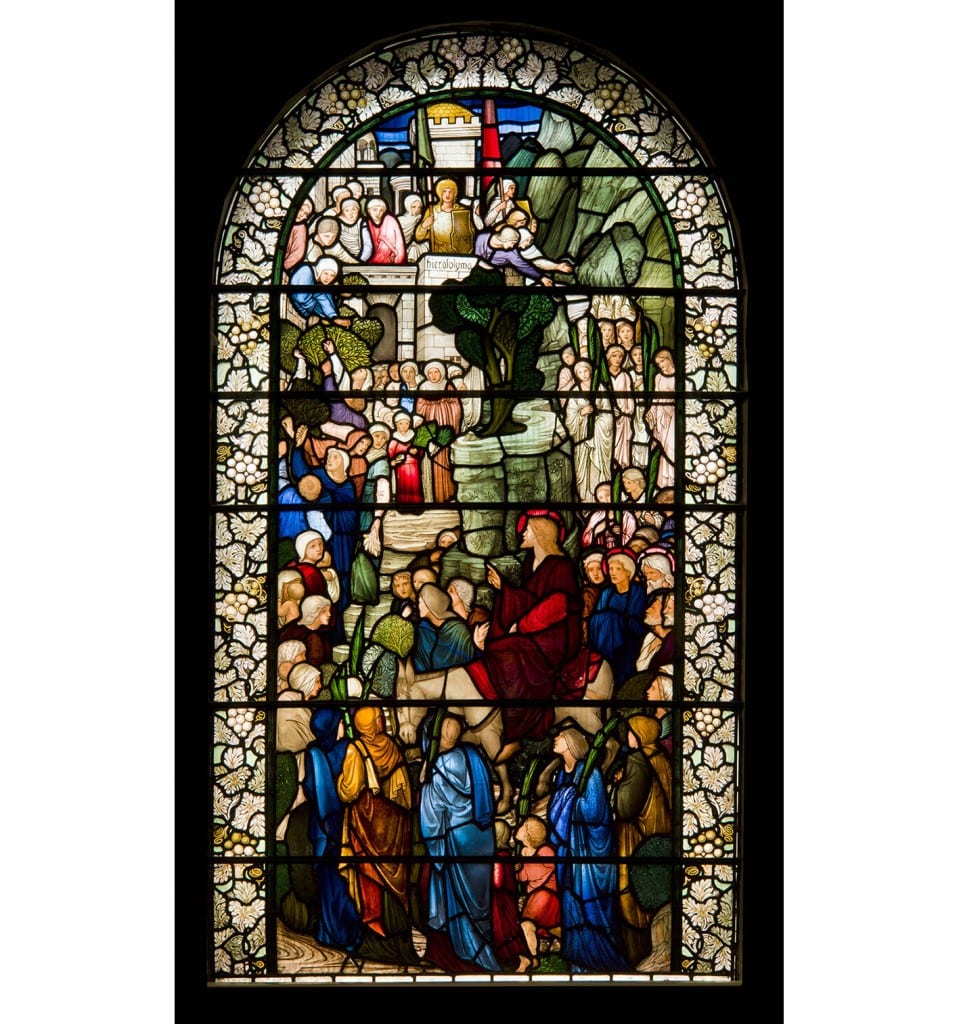

The proprietary chapel was acquired by the Crown in 1817, part of a peculiar arrangement to divest the Portland Estate of surplus ecclesiastical capacity. After a general overhaul it was dedicated to St Peter in 1832. Victorian alterations were of a generally high calibre, and included stained-glass windows by Edward Burne-Jones, all made by Morris & Co., that remain in place. The window at the centre of the south aisle gallery commemorates James Golding Snelgrove, a son of John Snelgrove (co-owner of the Marshall & Snelgrove department store on Oxford Street), who died aged sixteen. Below gallery level is a smaller companion window showing the ‘Reception of Souls into Paradise’. Burne-Jones noted the job in an account book, laden with mock outrage:

‘Large cartoon of Christ entering Jerusalem – for church of SS Marshall & Snellgrove [sic] – another masterpiece charged on so mean a scale of remuneration that I am reluctant to put on record so disgraceful a piece – nothing is so injurious to art as these contemptible prices – they keep alive the dishonest tendencies of the time more than can easily be said.’ [2]

The twentieth century saw gradual decline and after a protracted period of dry rot, de-Victorianizing and muddle, the church was adapted in 1982–3 for office use by the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity, which continues in occupation.

The Burne-Jones stained-glass window at the centre of the south aisle gallery, depicting ‘The Entry into Jerusalem’, dates from 1883 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

One of a pair of windows on the north side of the church, on the theme of Faith, Hope and Charity. The window was dedicated to John Snelgrove and made following his death in 1903 by Powells, possibly to designs by Henry Holiday (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The photographs for the Survey of London’s account of the south-eastern parts of the historic parish of St Marylebone are by Chris Redgrave, of Historic England. As an additional complement to our investigations, Andy Crispe, also of Historic England, has prepared a fly-through visualization of St Peter’s. We are pleased now to be able to make this publicly available.

Oxford Chapel 3D reconstruction by Andy Crispe from Survey of London on Vimeo.

References

[1] John Summerson, Georgian London, 2003 edn, p. 99

[2] Douglas E. Schoenherr, ‘Edward Burne-Jones’s Account Books with Morris & Company (1861-1900): an annotated edition’, Journal of Stained Glass, vol. 35, 2011

Close

Close