Park Crescent: John Nash, Charles Mayor and one of the severest bankruptcies in London building history

By the Survey of London, on 25 May 2018

The Park Crescent of today is a post-war replica. A combination of poor original building methods, wartime damage and heavy-handed reconstruction policies has left little or no old fabric from the ‘semi-circus’ conceived by John Nash and built with much difficulty between about 1812 and 1822. Even that was only half of the full circus Nash had planned. Yet despite those early failures, despite also its present lack of authenticity, Park Crescent remains one of London’s most memorable episodes of urban planning.

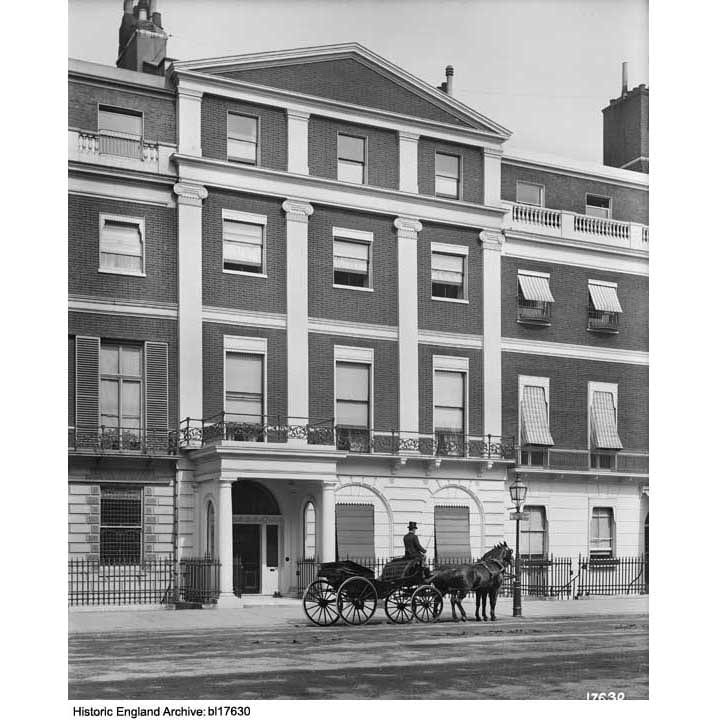

Park Crescent. Eastern crescent. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Three colonnaded circuses featured in Nash’s immortal scheme to link Whitehall and Westminster with Marylebone Park by way of what became Regent Street, as first published in 1811. All occupied critical junctures or points of transition, where traffic-ridden east-west routes broke the new line of procession, for Nash believed that the circus form invested such crossings with dignity and lessened the psychological sense of a barrier – something he strove to overcome so as to make the Crown’s developments around Regent’s Park feel accessible and eligible to Londoners of high standing. Confusingly, all three rond-points went at first by the informal name of Regent or Regent’s Circus. Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Circus, carved laboriously out of existing building fabric by compulsory purchase under the New Street Act of 1813, had to be quite small and in the event lacked the colonnades Nash had hoped for. Both have long gone, and though Oxford Circus survives as a concept, it is higher and slightly wider than Nash’s original creation.

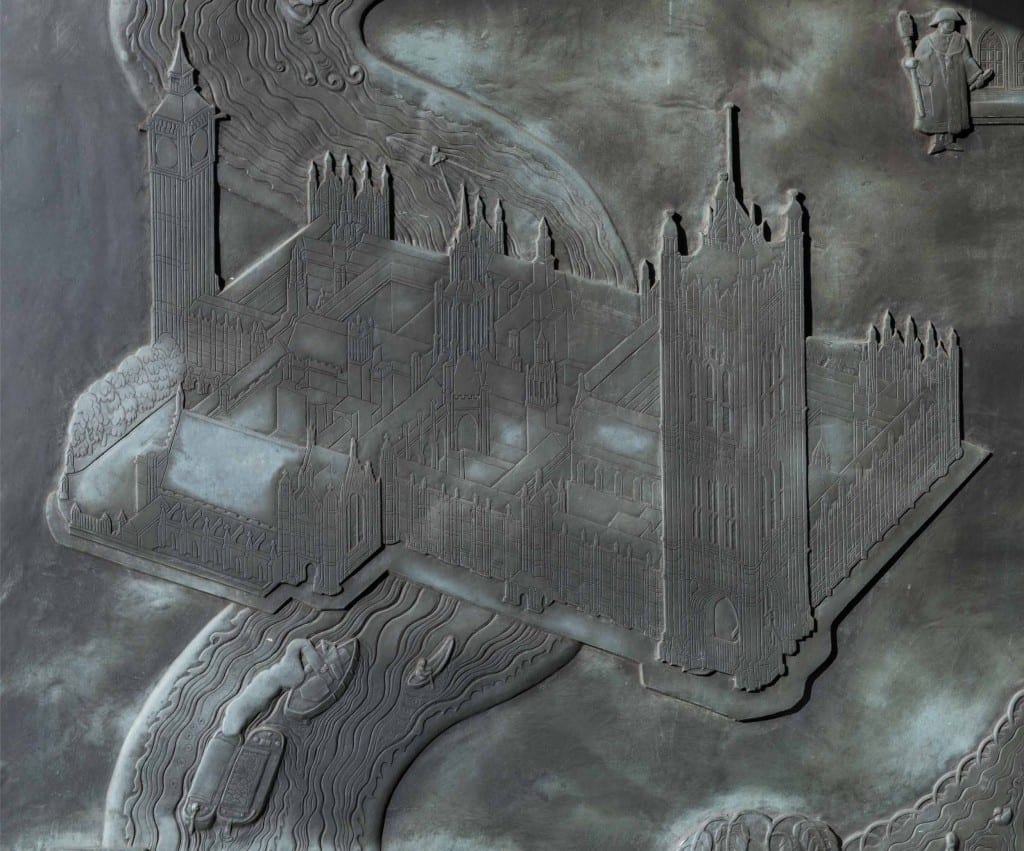

The third circus was to be different altogether. Over 500ft in diameter, it came at the point where the city eased into a gracious modern suburb, beyond the final obstacle of the New (now Marylebone) Road. But the shape and texture of that suburb shifted greatly over the years of its creation, with implications for the third circus. So much can be gathered from the fate of a fourth circus, the largest of all, devised by Nash as a central focus for Regent’s Park. Marked the Great Circus on the plan of 1811, when bands of continuous housing were anticipated within the park as well as on its periphery, it was then reserved for concentric terraces. Ultimately, it acquired a bare smattering of villas and became the Inner Circle, a low-key feature in the park landscape. With the opening-out of that landscape in the 1820s and the failure to develop the northern sector of the third circus, Park Crescent turned into a prelude to the park rather than the transitional interlude Nash intended.

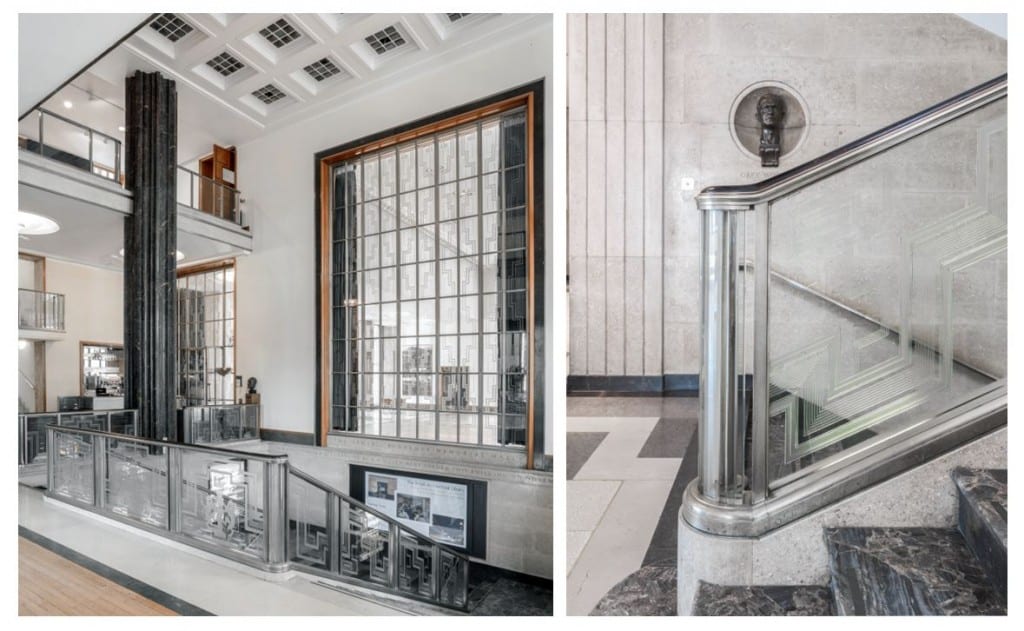

Park Crescent and Portland Place area from the west in 2011. (© Historic England, Damian Grady)

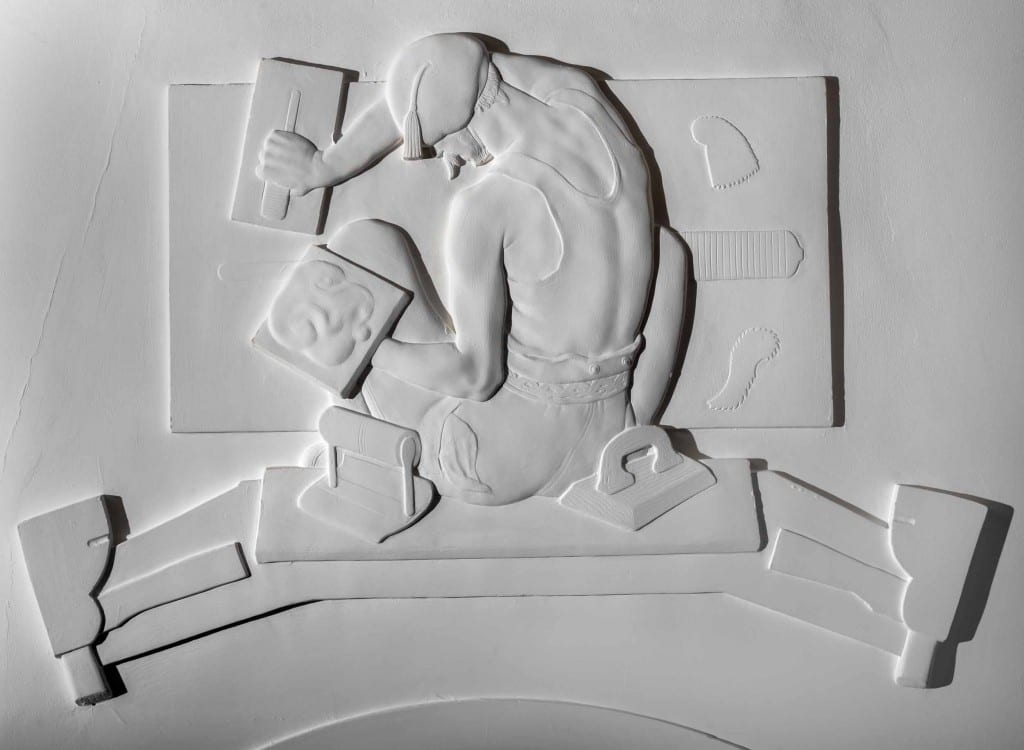

If the circus was the most striking of the crop in town-planning terms, it was also among the first elements of the Office of Woods and Forests’ plan for Regent Street and Regent’s Park to be implemented. Its site, Crown farmland, was in hand, so that it could be started even before the New Street Act authorised the complete scheme in 1813. Not surprisingly, Nash invested energy and urgency in getting it along. By the end of 1811 the hunt was on for a single builder brave and resourceful enough to take on both the whole of the circus, where Nash envisaged large first-rate houses, and the extension of Harley Street, for which he proposed brick-faced houses on narrower frontages. By March 1812 he had hooked his fish. ‘Mr Mayor is willing to adopt the elevation I had proposed to him, which is to encircle the whole with a collonnade of coupled columns surrounded [sic] by a ballustrade’. [1] Charles Mayor had started out as a jobbing carpenter and undertaker. In 1800 he successfully took over the north side of Brunswick Square from James Burton and built other houses near by. More to the point, he and Nash had been collaborating over a house in Foley Gardens south of Portland Place.

By May 1812 Nash and Mayor had worked out a detailed plan and schedule. Together they increased the diameter of the circus to 724ft, giving some houses frontages of up to 100ft but in consequence making them shallower and cramping the mews spaces behind. The timetable stipulated the first roofings-in and issuing of leases at the southern end to be by August 1814 and the final ones in the northern sector by August 1816. Nash projected Mayor’s overall outlay at about £300,000 and urged the Crown authorities to buy the improved ground rents so as to guarantee his liquidity. Mayor got the final go-ahead in July. Soon afterwards Nash was arranging to show his whole plan to the Prince Regent, telling Alexander Milne of the Woods and Forests: ‘It will be very impolitic not to pursue this course if we wish HRH to take up the measure con amore’. [2]

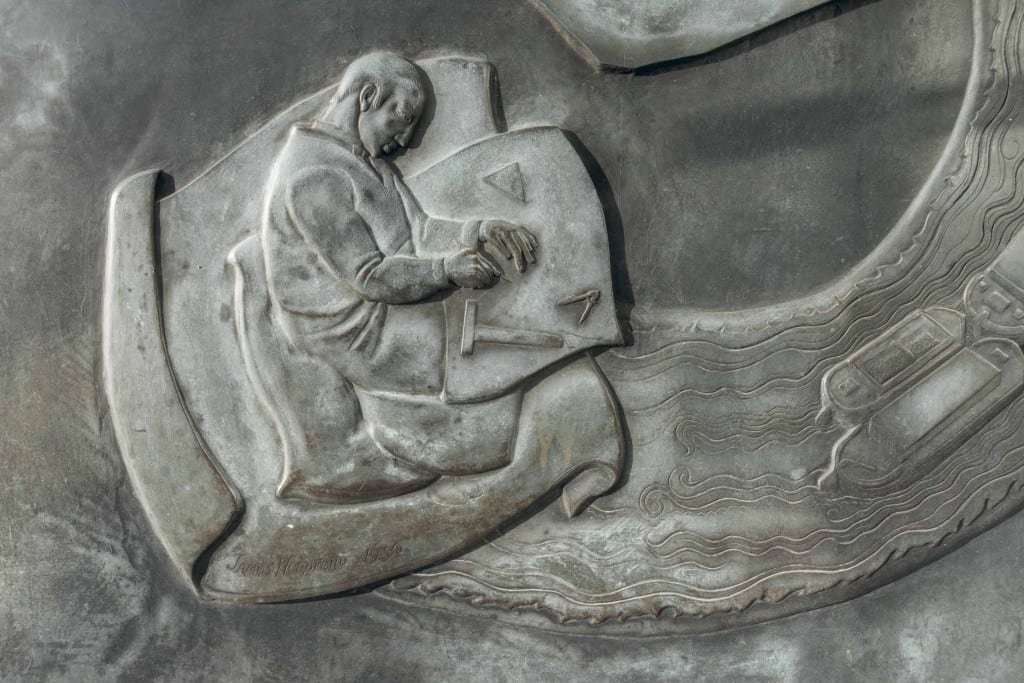

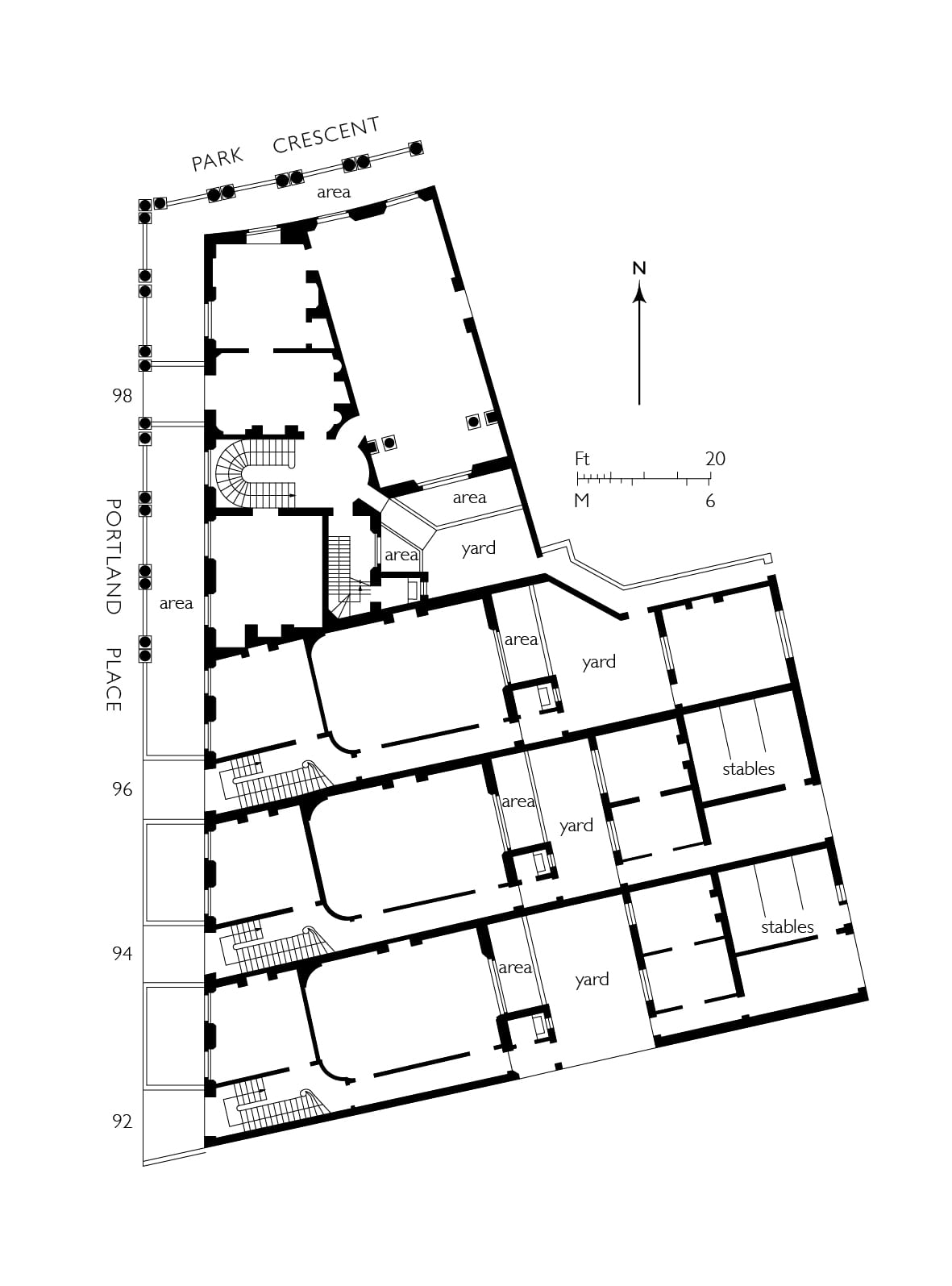

92–98 Portland Place. Original plan of houses as leased to Charles Mayor in 1813. From plans in the National Archives, CRES2/752. (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Mayor got going fast enough to ask for his first leases between December 1812 and August 1813. These concerned the southernmost houses on both sides of Regent’s Circus and also some smaller brick-fronted ones that were to connect Portland Place with the circus (Nos 77–81 on the west and 92–96 on the east). Though these leases were duly issued, little finishing work can have taken place within the carcasses. For financial reasons Mayor evidently hoped to secure as many leases as he could as fast as might be. To that end he appears to have embarked upon the cellars of almost the whole of the southern semi-circus and even to have done some excavation on the northern side of the New Road.

Then things started to unravel. With the Napoleonic Wars reaching their climax, it was a bad time for builders. Few people were in the market for houses, yet building materials were going up in price. Mayor seems to have done nothing elaborately tricky: with Nash egging him on, he just miscalculated and was drawn into one of the severest bankruptcies in London building history. His slow-down during 1813 must have been well-noted. ‘Every stimulus should be applied to Mr Mayor to complete his Circus,’ urged Nash in a report to the Commissioners on changes planned for the park that December, ‘which will carry that character of respectable building into the heart of the Park and tempt the higher classes of society to come there’. [3]

Park Crescent. Western crescent. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The first half of 1814 saw little progress apart from an intended pub built by James Smith of Norton Street on back land between Harley Street and the circus. In the autumn Mayor appealed to the Woods and Forests for a loan, admitting: ‘I am absolutely at a Stand Still’. Nash, asked for advice, reported just before Christmas with his usual optimism that with eleven houses covered in, another six up to the chamber floor, excavation in some state of forwardness for the whole of the circus and a million and a half bricks on site, the developer ought to have enough security to win through – ‘if the half circus can be completed in the course of the next year (I mean externally)… his speculation will have a favourable issue’. [4] With the Crown declining to lend, vary terms or purchase ground rents, the creditors deemed otherwise. Mayor was carted off to the Fleet Prison early in 1815 and the grindstones of bankruptcy began to turn.

Like other bankrupts, Mayor was allowed out on day release, and made efforts to realize his assets. He managed to let the Foley Gardens house, but a severe injury, incurred while inspecting one of the Regent’s Circus houses in February 1816, cannot have helped. One bankruptcy commission superseded another. So persistent was the post-war slump that Mayor’s assignees were wary of trying to finish the speculation themselves and disappointed when they tried to sell off assets. Meanwhile the carcasses in sundry states of scruffiness and dereliction scared off buyers.

Park Crescent and the New Road, looking west towards Marylebone parish church. From Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, 1822. (Wikimedia Commons, from ianvisits.co.uk)

John Shaw, the architect and surveyor to the Eyre Estate, claimed that it was thanks to ‘a very extraordinary man, Mr. Farquhar’, who put money in as a speculation, that building resumed at what was to become Park Crescent. This was the former East India Company’s gunpowder contractor, John Farquhar. He died in 1826 leaving property in the vicinity of Park Crescent, but no further evidence of his involvement has come to light. [5] In 1817 the Great Portland Street builder William Richardson, apprised that Mayor’s assignees were not going to complete the development themselves, sought terms for both the Harley Street continuation and for finishing the western half of the crescent, where foundations were partly laid. A bigger, City-based contractor, Henry Peto, then bought the three carcasses on the east side of Portland Place (Nos 92–96), completing them ‘in the first style of elegance’, and went on to take most of the eastern quadrant, excepting its tip, assigned to Samuel Baxter and the corner house No. 15. Peto bought the ground rent from this last from a mortgagee, but the house itself was evidently completed by Mayor’s assignees, who decided to sell it in 1820.

In the early stages Peto was hampered by the collapse of a party wall between two of the Portland Place houses during a storm in March 1818. There had been a bad fire in one of these in 1814, on which Nash blamed the fall. Peto was adamant that the houses had been built with bricks ‘mostly of the very worst description and totally unfit for use’, and laxly supervised – accusations that have haunted the Nash developments and Park Crescent in particular ever since – and commissioned an independent report to prove it. ‘I must beg to be allowed to treat the insinuations of my inattention and that of my clerks with contempt’, riposted Nash, adding that Peto ought to have noted the state of the houses when he bought them. [6]

On both sides of the crescent, finishing off Mayor’s carcasses generally preceded the building of the other houses. The western crescent went up mainly in 1819–20; at the same time Richardson undertook the east side of Upper Harley Street, essentially following the original Nash-Mayor plan. Judging from a sketch of Park Crescent in 1820, Peto had as yet made little or no progress with his side. Beyond Mayor’s houses at Nos 13–15, the eastern quadrant was just excavated ground and derelict-looking pavement vaults, while No. 13 was in a ruinous state, with bare roof timbers and fallen brickwork. Perhaps the last of the houses to be started were Baxter’s at Nos 1–6, the first two of which were still in carcass in July 1821. The whole can have been barely finished when Ackermann published his prospect of The Crescent, Portland Place in 1822.

Park Crescent. Eastern Crescent. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The name ‘Park Crescent’ is first encountered in the year 1821. By then it was abundantly clear that the half-circus north of the New Road would never go ahead. Ideas about the form of the park had radically changed, with a greater openness of landscape prevailing. Around 1820 Nash therefore scrapped the northern crescent altogether in favour of Park Square, square-sided with an open north end. The crescent furnished the park, the New Road and indeed London as a whole with a fresh and uplifting piece of unified urban scenery. Its semicircular profile, albeit only half of what had been planned, offered a decisive depth of sweep that an elliptical crescent would have lacked. On closer inspection the composition, as often with Nash, was sleek but shallow. Minimal projections and pediments at the ends do something to relieve the simple economy of the plastered elevations (originally in Roman cement, Bath-stone coloured, with the jointing perhaps sharper than it is today). But the main compositional trick is in the enfilade of the continuous ground-storey colonnade with coupled Ionic columns, a device integral to Nash’s overall New Street plan and surviving only here. The original agreement with Mayor lays some weight on the balustrades topping the parapets and colonnades, which were to be of stone, and on the iron fencing, which both fronted the deep continuous basements and ran laterally to shield the entrance bridges. As for the houses themselves, they were not the monster 100ft mansions Nash had first dreamt of, just good first-raters with fronts typically of 32ft, backs several feet wider, and ample stone staircases.

References

[1] The National Archives (TNA), CRES2/748.

[2] Ibid.

[3] TNA, CRES2/742.

[4] TNA, CRES2/752; B3/3365.

[5] Report from the Select Committee on Crown Leases, p. 50.

[6] TNA, CRES2/763.

Close

Close