Harley Street

By the Survey of London, on 13 October 2017

Harley Street has long been synonymous with the top echelon of the medical profession, a Harley Street consultant the apogee of the profession. This reputation was forged in the second half of the nineteenth century, and although it dimmed a little in the years after the Second World War, it enjoyed a resurgence in the late twentieth century with the growth of private health care.

General view of the west side of Harley Street looking south from New Cavendish Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Howard de Walden Estate and the Survey of London. © Historic England

The street itself has preserved its residential appearance, despite the fact that for the most part residence is now confined to upper-floor flats. It was first conceived in the early eighteenth century, but largely laid out and built up between the 1750s and 1780s. Although much Georgian fabric remains, there has been considerable rebuilding, particularly in the southern stretches of the street.

Detail of 1–5 Harley Street on the corner with Wigmore Street, designed by Robert J. Worley and built in 1896-9. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

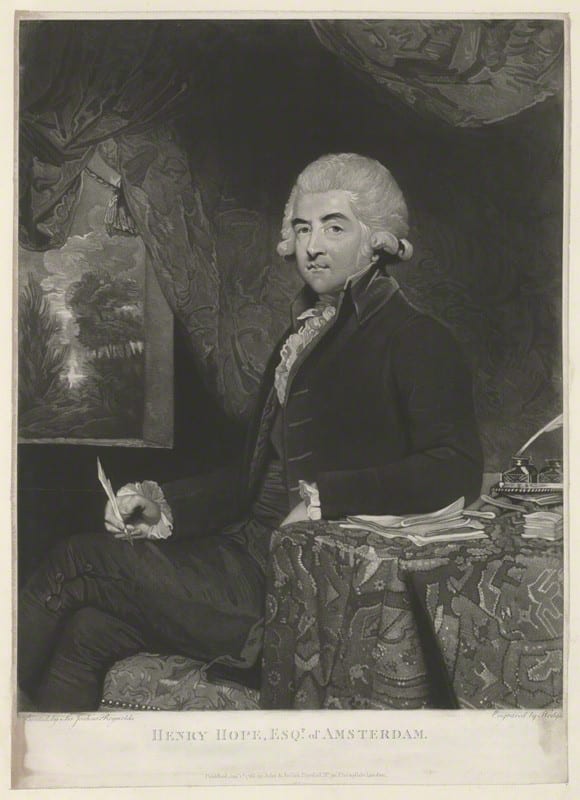

From the beginning Harley Street was one of the more fashionable addresses hereabouts, with aristocracy, gentry, politicians, high-ranking clergymen, military and naval officers resident for the London season. Here too were the portraitist Allan Ramsay, and J. M. W. Turner before he decamped round the corner to Queen Anne Street. Increasingly in the early nineteenth century wealthy merchants took up residence. Many owed their wealth to slavery, from sugar plantations in the colonies and later from the huge sums paid out in compensation to plantation owners following the abolition of the slave trade. Others had grown rich through the East India Company, so many that Harley Street became as notable for its ‘nabobs’ as it became for its doctors. As late as 1841 Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine reckoned that ‘the claret is poor stuff, but Harley Street Madeira has passed into proverb, and nowhere are curries and mulligatawny given in equal style’.

This general view of 74 to 82 Harley Street gives a good impression of the street’s Georgian character, and perhaps a sense of that monotony so disliked by the Victorians. The houses date from the 1770s, with the usual later alterations of balconies, stuccoed ground storeys and raised upper floors. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

During the earlier decades of Victoria’s reign members of parliament and lawyers were prominent in Harley Street. The street so epitomised dull respectability that it was chosen by Charles Dickens as the home of Mr Merdle in Little Dorrit, first published in 1855–7. Disraeli too, in Tancred published in 1847, derided ‘your Gloucester Places, and Baker Streets, and Harley Streets, and Wimpole Streets, and all those flat, dull, spiritless streets, resembling each other like a large family of plain children’. Disraeli’s great political opponent Gladstone occupied 73 Harley Street from 1876–82. His arrival coincided with his campaign on the Eastern Question, arising from the massacre of Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. On a Sunday evening in 1878 a ‘jingo mob’ gathered outside his house, hurling stones and verbal abuse at his windows.

73 Harley Street. Gladstone lived in the house previously on this site, which would have resembled those on either side. The present No. 73 was rebuilt in 1904 to designs by W. Henry White for the ophthalmic surgeon Walter Hamilton Hylton Jessop. The blue plaque commemorates not only Gladstone’s residence from 1876–82 but also Sir Charles Lyell who lived there from 1846–75. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

By this time Marylebone had long been associated with medicine. Indeed, medicine arrived at the same time as the housing boom of the 1750s onwards. Most of the early evidence relates to institutions for treating the poor. Hospitals, like housing, gravitated to healthy suburban locations close to open fields and fresh air. When the Middlesex Hospital was built on Mortimer street in 1757 it was at the very edge of the expanding city, as was the parish workhouse in Paddington Street.

Entrance to No. 118. The Georgian house on this site was rebuilt in around 1909–10 to designs by F. M. Elgood with stone carvings by A. J. Thorpe. Together with its neighbours to the south, Nos 114 and 116, it was reconstructed behind the retained façade in 2005–9 as consulting suites and a pathology laboratory for the London Clinic by the architects Floyd Slaski Partnership. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Today, Marylebone generally, and Harley Street in particular, is most closely linked with front-rank medicine and private consultants. From the mid eighteenth century, proximity to London’s teaching hospitals became important for top medical men who held prestigious posts in them. Closeness to aristocratic patients was another major consideration. By the 1840s there were sufficient eminent physicians and surgeons in Cavendish Square and Queen Anne Street to act as a magnet for others. However, around this time those at the top of their profession were as likely to reside south of Oxford Street as north. The medical directory for 1854 shows an even distribution between Marylebone, Mayfair and Bloomsbury.

Detail of the door to No. 72. The size and number of doctor’s brass plates were strictly controlled by the Howard de Walden Estate, with regular checks against the Medical Directory to weed out interlopers. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Harley Street’s subsequent primacy is probably accounted for by its immediate proximity to Cavendish Square – the acme of fashionable Marylebone. Even by 1874, when Harley Street’s significance was already established, being close to the square still mattered. In that year Sir Alfred Baring Garrod, physician and gout specialist, moved from 84 Harley Street further south to No. 10 simply to be nearer to Cavendish Square. Twelve years later the surgeon Sir John Tweedy’s move in the opposite direction, from No. 24 to No. 100, was regarded by colleagues as committing professional suicide.

For most of its history, the southern end of Harley Street was the more fashionable address. Nos 6 to 10 (to the left) were built in 1825–7, probably by the architect Thomas Hardwick. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

As fashionable society ebbed away from Marylebone in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a similar shift of smart medical practice might have been expected, but that never happened. By then many patients of all classes were travelling to see doctors rather than the reverse. But the main reason seems to have been that once a distinct medical community had been established it was found to be enormously beneficial to those within it. This professional interaction is recalled in many memoirs of consultants, who placed great value on the ability to call on the advice or second opinion of a neighbour. In the twentieth century there was also an active policy on the part of the Howard de Walden Estate to preserve the Marylebone grid as a medical enclave.

Nos 51 (left) and 53 Harley Street. No. 51 was built in 1894 to designs by F. M. Elgood for the surgeon William Bruce Clarke on the site of the Turk’s Head pub. No. 53 was designed by Wills & Kaula and completed in 1914–15 as a home and practice for the surgeon and urologist Frank Seymour Kidd. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

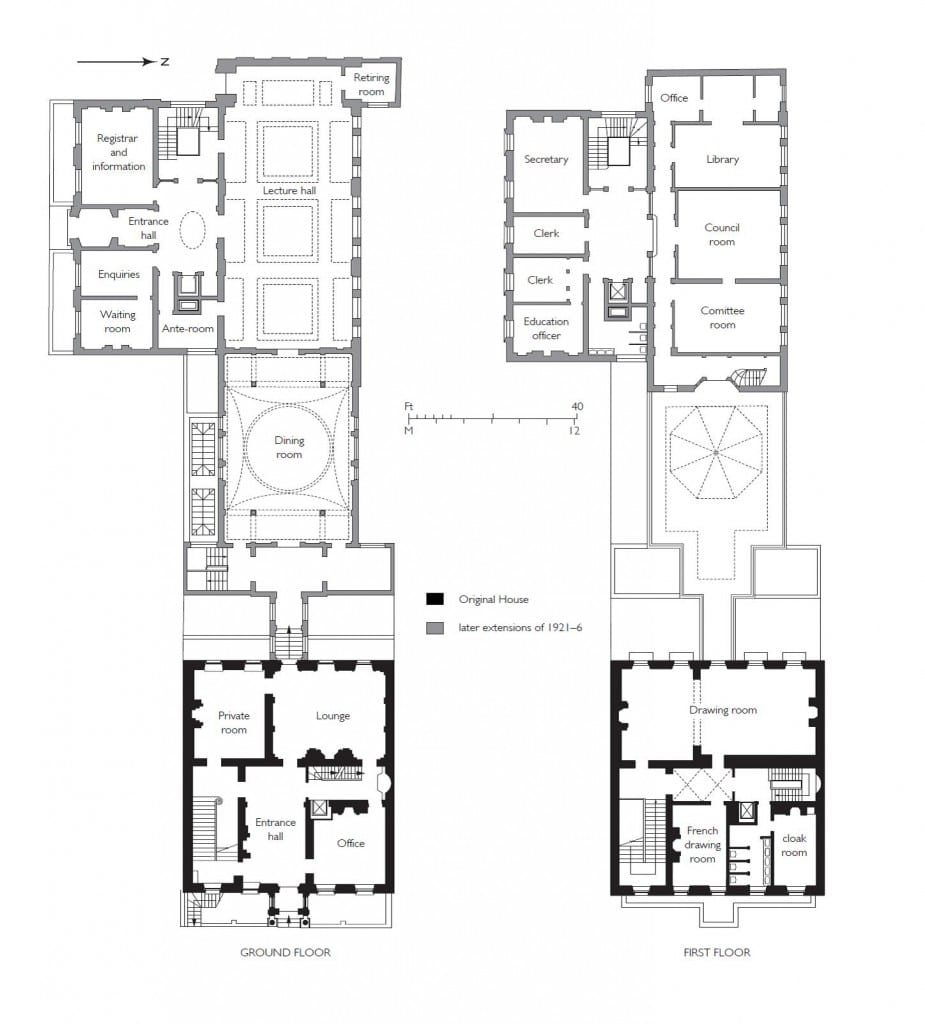

The image of the Harley Street doctor relies much on the traditional kind of premises he inhabited. The standard London town house needed little alteration to turn it into a doctor’s house. Ground-floor front rooms became waiting rooms instead of dining rooms, with a consulting room either immediately behind or in the closet wing.

Nos 82 to 86 Harley Street. No. 84 in the centre was rebuilt in 1909 to designs by Claude W. Ferrier. The neurologist Walter Russell Brain had consulting rooms in No. 86 (on the left) in the 1960s. This retains its rich Georgian interior and was home to Russian ambassadors after 1780, including Count Simon Woronzow and Prince Andreyevich Lieven. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Originally, the doctor’s dependants occupied the remainder of the house above, but after families moved to the suburbs, houses might be converted or rebuilt as suites of consulting rooms for multiple medical occupation.

Nos 40 and 42 Harley Street show the contrasting architectural taste of the 1890s (No. 42 on the left, by C. H. Worley, brother of Robert J. Worley) and 1930s (No. 40, on the right, by Charles W. Clark, architect to the Metropolitan Railway Company). No. 40 was designed to resemble a private house but provided suites of consulting rooms behind a modish Art Deco entrance hall. No. 42 decked in Worley’s characteristic orange-pink terracotta was given Jacobean-style interior decor. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

In the later twentieth century many consultants gave up their private rooms for the better-equipped universities and hospitals. In their place came alternative practitioners and aesthetic therapists for whom the individual consulting rooms in elegant domestic settings provided a soothing backdrop. In the latest conversions encouraged by the Howard de Walden Estate there has been a policy of reconstruction to create purpose-built consulting suites over reinforced basements, allowing the latest diagnostic equipment to be installed behind retained facades, which preserve the historic character of the district.

Early twentieth century Birn Brothers postcard, poking fun at the Harley Street consultants and their patients. © H. Martin. Reproduced by permission of H. Martin

Close

Close