Montagu House, Portman Square: the story of a lost Georgian town palace

By Survey of London, on 17 September 2021

This blog post was written for the Survey of London by Rory Lamb, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, who researched the history of Montagu House for the Survey this summer, during a two-month work placement funded by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts & Humanities Doctoral Internship Programme. Rory’s research will contribute towards the Survey’s study of South-West Marylebone, scheduled for publication as volume 56 in the Survey’s ongoing series of area volumes. (Volumes 54 & 55, on Whitechapel, are the next volumes to be published, in June 2022.)

Until the mid-1950s, the site of the Nobu Hotel and Portman Towers at the north-west corner of Portman Square in Marylebone was occupied by Montagu House, a freestanding townhouse set in one of London’s largest private gardens. Latterly the town residence of the Portman Estate’s landlords, the Viscounts Portman, it was for a century occupied by the descendants of Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, the celebrated eighteenth-century writer and hostess for whom it was executed between 1775 and 1791. In Private Palaces of London (1908), Edwin Beresford Chancellor summed up her significance for the building:

Perhaps hardly another important mansion in London is so closely identified with a single individual as is the great house in Portman Square with its first owner. This is due to two reasons, one of which is the close and almost tender interest taken by Mrs Montagu in its construction and decoration; and the other the renown of the lady herself.

Mrs Montagu was the author of a famous essay on Shakespeare and a leading member of the Bluestockings, a group of men and women who met to discuss literature and philosophy at her London houses and those of her friends. Gambling and politics were banned from Mrs Montagu’s gatherings, which usually took the form of a sumptuous breakfast, tea or dinner followed by group conversations on intellectual subjects. From the 1750s her salon at No 23 Hill Street in Mayfair was attended by the likes of Edmund Burke and Sir Joshua Reynolds and sought out by literary visitors to London from abroad. When her husband, Edward, died in 1775, Mrs Montagu inherited a large fortune and set about constructing a new house in Marylebone which would offer an expanded capacity and a more magnificent setting for her hosting. For her architect she turned to James ‘Athenian’ Stuart (not Robert Adam as has sometimes been claimed), whom Mrs Montagu had previously employed at Hill Street and whom she had assisted in publishing the Antiquities of Athens in the 1760s.

Elizabeth Montagu (née Robinson) by John Raphael Smith after Joshua Reynolds, 1776 (© National Portrait Gallery, London [reference: NPG D13746], shared without changes under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license).

Montagu House, illustrated by T. H. Shepherd, 1851 (from Mrs Montagu, ‘Queen of the Blues’: Her Letters and Friendships from 1762 to 1800, Vol. 2, edited by Reginald Blunt [Boston and New York, 1923], p.110).

The interiors of the principal apartment were decorated over the next four years before Mrs Montagu was able to take up residence in December 1781. These comprised a ground-floor staircase hall rising to a circuit of four reception rooms: an antechamber, dining room, morning room (giving access into Montagu’s private apartment) and gallery. The antechamber was decorated in the Pompeiian style by Biagio Rebecca and Giovanni Battista Cipriani akin to the painted room of Spencer House, and the gallery featured paintings on Shakespearean subjects as the backdrop for Montagu’s literary gatherings. The ceilings offered delicate geometric and floral patterning in the hall and dining room, with more elaborate coffered coving in the morning room and an elliptical vault of interlocking fans and scrollwork with paintings by Angelica Kauffman in the gallery. ‘All the celebrated artists in England of the present times have done something towards embellishing my house’, wrote Mrs Montagu to Lord Kames in December 1781, ‘but its best grace is simplicity’. A small suite of three rooms had also been fitted up on the ground floor beneath Mrs Montagu’s bedroom for her friend Leonard Smelt, tutor to two of George III’s sons, and his wife during their visits to London. From 1780 Smelt had co-ordinated ticketed public visits to the new reception rooms in the final stages of their completion. Despite the craftsmen’s concerns that visitors would damage the paint and gilding, Mrs Montagu insisted tickets should be widely distributed so as to show off her new house to the whole of London society.

The dining room, 1904 (from A Later Pepys: the correspondence of Sir William Weller Pepys etc., Vol. 2, edited by Alice C. C. Gaussen [London, 1904], p.279).

The morning room in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12699).

However, Stuart himself, and his unsatisfactory assistant, James Gandon, seem to have been dismissed some time in 1780-1, Stuart’s drunkenness and incompetence with the workmen sitting at odds with Mrs Montagu views of decorous behaviour and the close eye she kept on budget and efficiency in her affairs. He was replaced as architect by Joseph Bonomi, assisted by her head carpenter, Charles Evans. When Mrs Montagu moved in most of the ground-floor rooms and the great room of the first floor remained incomplete and work on these resumed between 1789 and 1791. During this period the first-floor morning room was transformed into her feather-room, celebrated in verse by William Cowper, with timber panels hung with tapestries of exotic feathers collected by Mrs Montagu’s friends over the preceding decade. The focus of the new work, however, was the decoration of the great room to a handsome Neoclassical design by Bonomi. This was a much richer interior than Stuart’s earlier rooms, dominated by fourteen scagliola Corinthian pilasters, with profuse gilding, marble chimneypiece and window architraves, and a segmental ceiling of elaborate plasterwork. Montagu intended the luxurious decoration as a ploy to rival worldlier London hosts with a set piece of similar magnificence that would attract younger members of society to her polite parties and away from more debauched venues elsewhere. Bonomi’s grand interior was opened in great state by members of the royal family and celebrated in the St James’s Chronicle. Although the intellectual heyday of the Bluestockings was seen to have been at Hill Street, Mrs Montagu’s entertainments continued at Portman Square to increased scale and grandeur until her death in 1800, with breakfasts and teas attended by several hundred people.

The great room in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12693).

The semi-rural location of the house originally attracted Mrs Montagu, with an urban front to Portman Square but a rear elevation giving views from the first-floor dining room over fields to the Hampstead Hills. By the time of her death in 1800 much of this open character still remained but as Marylebone spread north and obscured the view a considerable green space was preserved by the Montagu House garden, expanded in 1789 but originally laid out by Mrs Montagu’s friend George Harcourt, 2nd Earl of Harcourt, whose flower gardens at Nuneham Courtenay in Oxfordshire she had admired. These also had an intellectual bent, Harcourt’s garden designs being inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas of philosophical contemplation in nature. However, the gardens of Montagu House were best remembered for playing host to Mrs Montagu’s annual chimneysweeps’ dinner, held on May Day from 1789 in the forecourt to the square. The meal was open to all of London’s sweeps who were served roast beef and plum pudding by her footmen on trestle tables and became something of an annual society spectacle.

Montagu House and gardens with the new stable block in 1895 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland).

Montagu House remained in Elizabeth Montagu’s family until 1872, when Selby’s original 99-year leases reverted to the Portman family. It was then occupied by Mrs Montagu’s adopted heir and nephew, Matthew Robinson Montagu (latterly 4th Baron Rokeby), and his children, concluding with his younger son General Henry Montagu, 6th Baron Rokeby. In 1872 the general, a veteran of Waterloo now resigned to a wheel-chair due to gout and old age, was forced to vacate the family home for a house in Stratford Place. He was replaced by William Henry Berkeley Portman, MP, who had been living on the south side of Portman Square for several years. Before succeeding as 2nd Viscount Portman in 1888, Portman had already made considerable changes to Montagu House, possibly under the direction of the incumbent RIBA president, Thomas Henry Wyatt, who was commissioned for survey drawings in 1872. The Ionic doorway was extended into a large porte cochere of Portland Stone and matching bracketed balconies added to the first floor Serlian windows. An attic story with additional bedrooms and pedimented dormer windows was added to the garden front, and an early lift system was inserted into the void of the service stair. Portman also cut back the now mature gardens and gave over a large area of ground on the north side for a new courtyard stable block opening on to George Street.

Exterior view of 22 Portman Square, photographed in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12691).

The Portman family continued in occupation of the house until the Second World War, when it was gutted by an incendiary bomb during an air raid in 1941. It stood as an empty shell for about a decade before being demolished in the early 1950s along with the undamaged stable block. One of the last surviving features of Montagu House was a set of Stuart’s gate piers, which were relocated to Kenwood House in Hampstead. The site was briefly used for a car park before the construction of the present hotel and flats. Although the grand mansion has been lost, Mrs Montagu’s name is preserved in Montagu Street, west of the block on which the house stood, while her earlier house at Hill Street (now No. 31) was rediscovered in 2003 with intact interiors by Stuart and Robert Adam. Since then, the Bluestockings have been a popular subject for scholarship, Mrs Montagu remaining a central figure, with the result that her significance as an architectural patron is now better recognised alongside her intellectual achievements.

Whitechapel Bell Foundry

By the Survey of London, on 14 May 2021

It was announced today that permission is to be granted for a hotel conversion of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. It is timely, and sad, to repost this account from December 2016.

On 2 December it was announced that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry will close in May 2017. This will mark the end of what has been a remarkable story. Business cards claim the bell foundry as ‘Britain’s oldest manufacturing company’ and ‘the world’s most famous bell foundry’ – the first not readily contradicted, the second unverifiable but plausible. It has been said that the foundry ‘is so connected with the history of Whitechapel that it would be impossible to move it without wanton disregard of the associations of many generations.’[1] The business, principally the making of church bells, has operated continuously in Whitechapel since at least the 1570s, on its present site with the existing house and office buildings since the mid 1740s.

Shopfront at the east end of 32–34 Whitechapel Road in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The foundry’s origins have been traced to either Robert Doddes in 1567 or Robert Mot in 1572, giving rise to a traditional foundation date of 1570. It is said then to have been in Essex Court (later Tewkesbury Court, where Gunthorpe Street is now). There is no continuous thread, but it has also been suggested that the Elizabethan establishment had grown out of a foundry in Aldgate that can be tracked back to Stephen Norton in 1363.

Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 2010, from the north-east at the corner of Whitechapel Road and Plumber’s Row (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

From 1701 Richard Phelps was in charge. He made the great (5¼ ton) clock bell for St Paul’s Cathedral in 1716. When he died in August 1738 he was succeeded by Thomas Lester, aged about 35, who had been his foreman. It has been supposed that within the year Lester had moved the foundry into new buildings on the present site on Whitechapel Road, a belief which can be traced to Amherst Tyssen’s account of the history of the foundry in 1923, where he related that ‘according to the tradition preserved in the foundry and communicated to me by Mr John Mears more than sixty years ago, Thomas Lester built the present foundry in the year 1738 and moved his business to it. The site was said to have been previously occupied by the Artichoke Inn.‘[2] That has never been corroborated and it is implausible as such a move would take more than a few months.

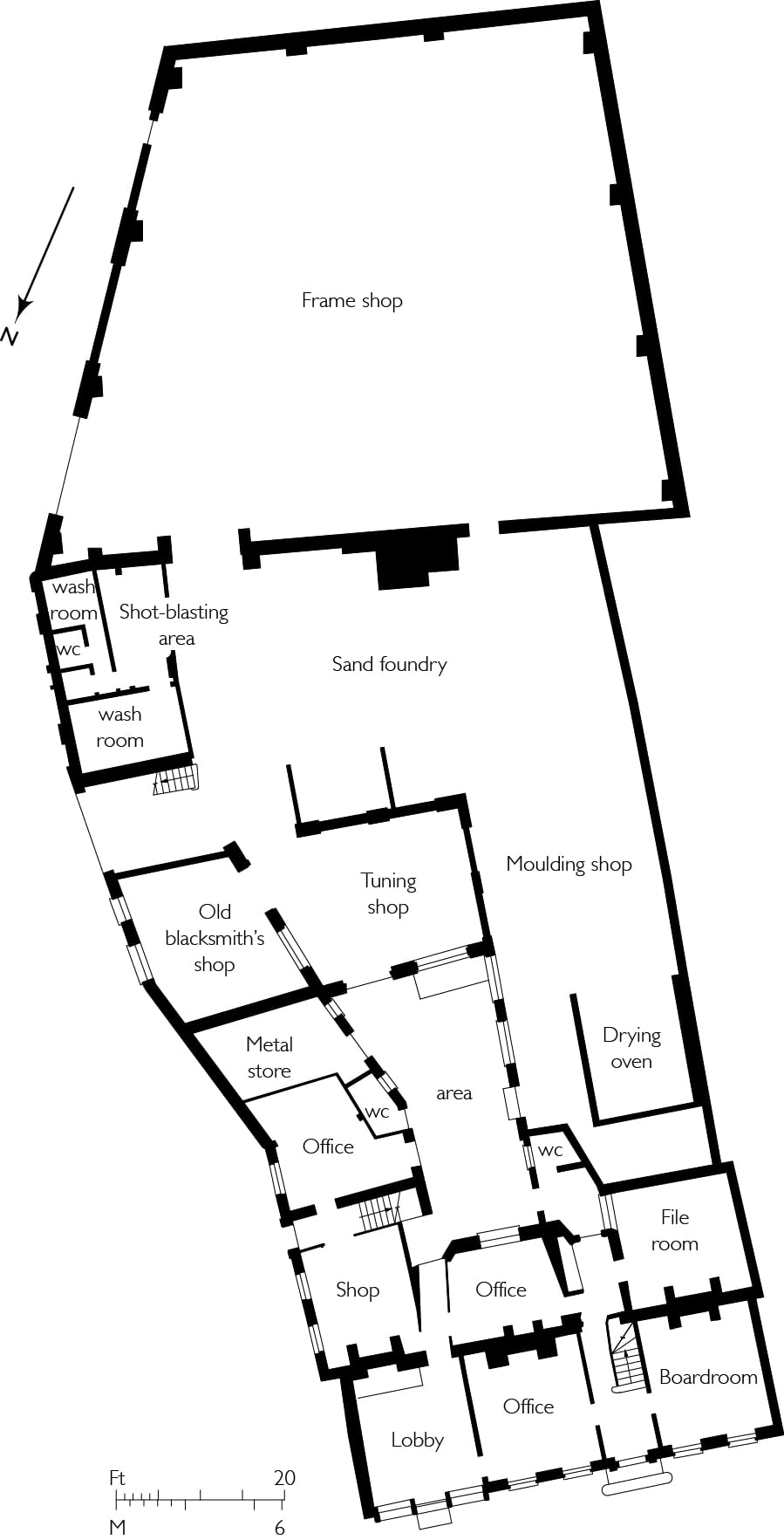

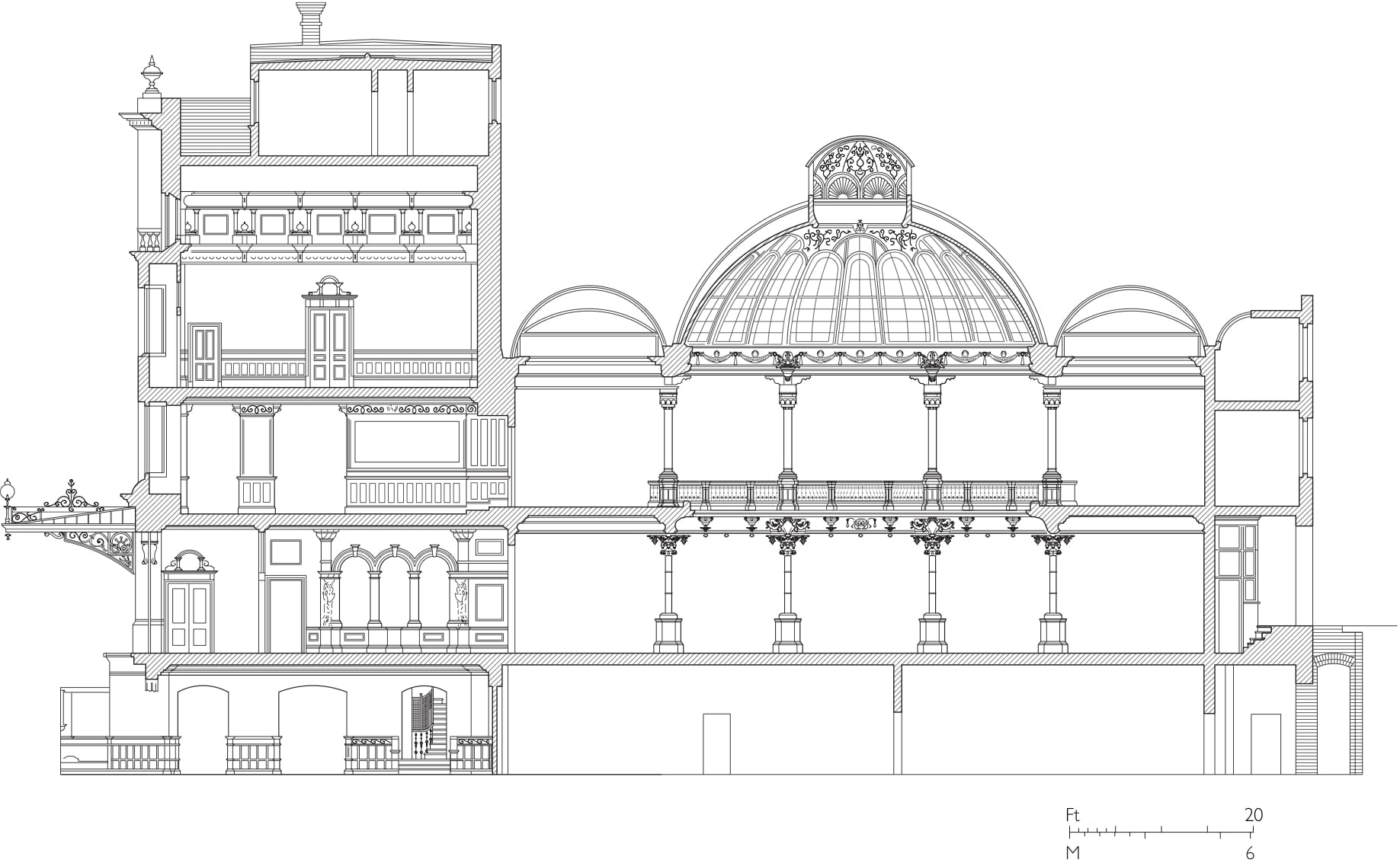

Ground-floor plan of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Contemporary documentation suggests a slightly later date for the move. An advertisement in the Daily Advertiser of 31 August 1743 reads: ‘To be let on a Building Lease, The Old Artichoke Alehouse, together with the House adjoining, in front fifty feet, and in Depth a hundred and six, situated in Whitechapel Street, the Corner turning into Stepney Fields.’ Those measurements tally well with the foundry site. Stepney Manor Court Rolls (at London Metropolitan Archives) refer to ‘the Artichoke Alehouse, late in the occupation of John Cowell now empty’ on 8 April 1743 and to ‘a new built messuage now in possession of Thomas Leicester, formerly two old houses’ on 15 May 1747. A sewer rates listing of February 1743/4 does not mention Lester at the site. The advertised building lease was no doubt taken by or sold on to Lester, who undertook redevelopment of the site in 1744–6, clearing the Artichoke. The motive for the move would have been the opportunity for a larger foundry and superior accommodation on this more easterly and therefore open site.

View of the Bell Foundry’s workshops from the roof of the front range, looking south in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The seven-bay brick range that is 32 and 34 Whitechapel Road is a single room deep with three rooms in line on each storey, all heated from the back wall. It was built to be Lester’s house and has probably always incorporated an office. The Doric doorcase appears to be an original feature, while the shopfront at the east end is of the early nineteenth century, either an insertion or a replacement. Internally the house retains much original fielded panelling, a good original staircase, chimneypieces of several eighteenth- and nineteenth-century dates and, in the central room on the first floor, a fine apsidal niche cupboard. Behind the east end is 2 Fieldgate Street, a separately built house of just one room per storey, perhaps for a foreman. Its Gibbsian door surround is of timber, as is its back wall.

The ground-floor front ‘lobby’ (former shop) at 34 Whitechapel Road in 2010, showing the casting profile of Big Ben over the front door (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Eighteenth-century outbuildings to the south are single storeyed: a former stables, coach-house and smithery range along Fieldgate Street; and the former foundry (latterly moulding shop) itself, across a yard behind the west part of the house. Facing the street on the former stabling range is a tablet inscribed: ‘This is Baynes Street’ with an illegible date, perhaps 1766, a reference to what later became Fieldgate Street. This junction, which now incorporates Plumber’s Row, bisected property owned by Edward Baynes from 1729.

Plumber’s Row range in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tablet inscribed ‘This is Baynes Street’ on the foundry’s former stabling range (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Thomas Lester took Thomas Pack into partnership in 1752 and acquired ownership of the foundry from a younger Edward Baynes in 1767. Lester’s nephew William Chapman was a foundry foreman who, working at Canterbury Cathedral in 1762, met William Mears, a young man he brought back to London to learn the bell-founding trade. Lester died in 1769 and left the foundry to relatives to be leased to Pack and Chapman as partners. After Pack died in 1781 Chapman was pushed out and for a few years descendants of Lester ran the establishment. Their initiative failed and William Mears returned in partnership with his brother Thomas, who came to Whitechapel from Canterbury. Ownership of the property remained divided among descendants of Lester and in 1810 Thomas Mears was still trading as ‘late Lester, Pack and Chapman’. On a promotional sheet he listed all the bells cast at the foundry since 1738, 1,858 in total, around 25 per year – including some for St Mary le Bow in 1738, Petersburg in Russia in 1747, and Christ Church, Philadelphia, in 1754.

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking north-west in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

A son, also Thomas Mears, acquired full control of the foundry in October 1818 when Lester’s descendants sold up. The younger Mears took over the businesses of four rival bell-founders and undertook works of improvement. By 1840 the firm had only one major competitor in Britain (W. & J. Taylor of Oxford and Loughborough). The next generation, Charles and George Mears, ran the foundry from 1844 to 1859, the highlight of this period being the casting in 1858 of Big Ben (13.7 tons), still the foundry’s largest bell. From 1865 George Mears was partnered by Robert Stainbank. Thereafter the business traded as Mears & Stainbank up to 1968. Arthur Hughes became the foundry manager in 1884 and took charge of operations in 1904.

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking south in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Given the ownership history, there was little significant investment in the buildings before 1818. However, the smithery end of the eastern outbuilding does appear to have been altered if not rebuilt between 1794 and 1813. Around 1820 a small pair of three-storey houses was added beyond a gateway that gave access to the foundry yard. There are also early nineteenth-century additions behind the centre and west bays of the main house, the last room incorporating a chimneypiece bearing ‘TM 1820’. Thereafter, possibly following a fire in 1837 or in the 1850s, the smithery site was redeveloped as a three-storey workshop/warehouse block extending across a retained gateway. In 1846 the foundry was enlarged with a new furnace by enclosing the south end of the yard, to make an 11.5 ton bell for Montreal Cathedral. Another furnace was added in 1848 when a tuning machine was housed in a specially built room that ate further into the yard with a largely glazed north wall. Two years later a 62ft-tall chimney was erected against the south wall. A large additional workshop or back foundry had been added to the far south-west by the 1870s, by when the pair of houses to the south-east had been cleared for a carpenter’s shop, the front wall retained with its doors and windows blocked. The whole Plumber’s Row range has latterly been used for making handbells and timber bell wheels.

Handbell workshop in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Moulding shop, showing moulds being prepared in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The back foundry was damaged during the Second World War. Proposals to rebuild entirely behind the Whitechapel Road houses emerged in 1958 by when the foundry was already protected by listing. The workshops were considered expendable, but even then it was suggested that the timber jib crane on the east wall should be preserved. First plans were shelved and a more modest scheme of 1964–5 was postponed for want of capital, though plant and furnaces were replaced and there were repairs. In 1972 Moss Sprawson tried to acquire the site for office development. For the foundry, Douglas Hughes (one of Arthur’s grandsons) proposed a move east across Fieldgate Street to what was then a car park owned by the Greater London Council. A move entirely out of London was also considered. The GLC’s Historic Buildings Division involved itself in trying to maintain what it considered ‘a unique and important living industry where crafts essentially unchanged for 400 years are practised by local craftsmen.’[3] But plans came unstuck again in 1976 when the GLC conceded it had no locus to help keep the business in situ. In the same year the UK gave the USA a Bicentennial Bell cast in Whitechapel.

A large new engineering workshop was at last built in 1979–81, with James Strike as architect. At the back of the site, it was faced with arcaded yellow stock brick on conservation grounds. In 1984–5 the GLC oversaw and helped pay for underpinning and refurbishment of the front buildings. The shopfront was grained and the external window shutters were renewed and painted dark green. In 1997 proprietorship passed to Douglas Hughes’s nephew, Alan Hughes, and his wife, Kathryn. The foundry has since continued to manufacture, though not without growing concerns as to its tenability in Whitechapel. Now the Hughes have announced that the foundry will close in May 2017 after sale of the site. The future of the business is to be negotiated.

We are very grateful to Alan Hughes for showing us round the premises and sharing his knowledge of the foundry.

The Survey of London has launched a participative website, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at: https://surveyoflondon.org. We welcome contributions from any and all. For more information about the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, and to add your memories and photographs, please visit https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/155/detail/.

Sand foundry, filling the moulds in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tuning shop in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Bell recast in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

References

[1] D. L. Munby, Industry and Planning in Stepney, 1951, p. 254

[2] Amherst D. Tyssen, ‘The History of the Whitechapel Bell-Foundry’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, vol. 5, 1923, p. 211

[3] London Metropolitan Archives, LMA/4441/01/0821

Selfridges, 398–454 Oxford Street

By Survey of London, on 23 December 2020

Thank you for reading the Survey of London’s blog posts over the last year. A highlight of this year for the Survey has been the publication of Volume 53 on Oxford Street in April, edited by Andrew Saint. While it was necessary to cancel the book launch event due to the public health crisis, we have been delighted to see positive reviews of the volume.

The book is already out of print (only a few copies may be purchased through online retailers), but we hope that more copies will be printed in the future. The volume is not currently as accessible as we would like; only the draft text is freely accessible through our website. As we work towards a more permanent solution to sharing the Survey’s volumes online, we plan to post extracts on our blog.

Last week, we were pleased to learn that the listing of Selfridges department store in Oxford Street has been upgraded by Historic England from Grade II to II*. To help lift the gloom at a time when shopping on Oxford Street and much else is closed to us, this blog post celebrates the Selfridges store, the grandest of Oxford Street’s shops. Selfridges occupies the whole of the lengthy block between Duke Street and Orchard Street on the north side of Oxford Street. This extensive site is the subject of a chapter in Volume 53. Chapter 10 concentrates on the complicated story of Selfridges’ architecture, focusing on the original building erected between 1907 and 1928.

We would like to wish our readers a restful Christmas break and our best wishes for a happy and healthy New Year.

The south-west corner of Selfridges, looking east along Oxford Street from above Orchard Street (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

It is well known that Selfridges was established by Harry Gordon Selfridge, who arrived in London from Chicago in May 1906. Forty-eight years of age and unknown in England, he came with the express intention of founding a great department store on the lines of the Marshall Field Store in Chicago, where he had risen from a lowly position to that of junior partner and the dynamic head of retailing, before retiring in 1904 after 24 years of service.

Selfridges, front. Details of the original elevation (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Selfridge was briefly equal partners in the venture with Samuel Waring, director of the Waring & Gillow department store further east at 164–182 Oxford Street. That store was rebuilt in 1904–6 to ambitious designs by R. Frank Atkinson. Selfridge & Waring Ltd, founded in 1906, was a short-lived arrangement. Waring played a full part in negotiating permissions for the new store until financial setbacks forced him to resign eighteen months later. By 1908, the project had become Selfridge’s alone.

Selfridges, floor plans in 1907, showing the original portion of the store at 406–422 Oxford Street, before the corner with Duke Street came into possession, with the division of the interior by party walls (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Selfridge had enlisted D. H. Burnham & Co., pre-eminent Chicago architects who counted department stores among their specialities and had undertaken work at the Marshall Field Store. Selfridge knew the equally dynamic Burnham and members of his firm well. The first drawings for Selfridges will have emanated from the design division of D. H. Burnham & Co. in Chicago. We do not certainly know who designed them, but the likeliest candidate is Ernest Graham, then Burnham’s right-hand man. The design for the front was altered and enriched by Francis Swales, a Canadian-born architect who had been working in London on a freelance basis for a few years. Swales was paid a one-off fee for his work on the design by Selfridge & Waring Ltd in November 1906, well before the plans for the store had been finalized, and had no more to do with the project. In 1907, Waring’s architect Frank Atkinson was brought in to make changes to the plans to fit the London County Council’s fire regulations.

Original block as completed, 1909. Duke Street to the right (Historic England Archive, BL20582/001)

The LCC gave the go-ahead in July 1907, and construction began by the Waring-White Building Company. That firm had signed a contract with Selfridge & Waring Ltd to build the new store the previous autumn, but could not get beyond clearing the site, excavating and putting in retaining walls (a substantial job, since there were to be three floors of basement). The first phase of the Selfridges store, initially 406–422 Oxford Street, was opened in 1909.

Original block as completed, 1909 (Historic England Archive, BL20507)

Selfridges was revolutionary in several ways. It employed a rational, gridded plan, familiar in London from warehouse buildings but seldom exploited hitherto by British retailers. It took up American advances in metal-framed structures and fast-track construction, and it may have been planned from the start for enlargement westwards; the original portion opened in 1909 was only a third of the final length of frontage, stretching all the way from Duke Street to Orchard Street. These were technical matters. What the public saw was a classical front of unprecedented audacity and swagger, surpassing not just Waring & Gillow but even the department stores of America, not to mention London’s public and bank buildings.

Ladies’ dresses department at the time of opening in 1909 (from a glass slide acquired by the Survey of London)

China department in 1909 (from a glass slide acquired by the Survey of London)

At a time of international emulation and exchange in urban architecture, Selfridge and his architects demonstrated that retailing was a pursuit deserving the highest dignity. That is the achievement of Selfridges, and one that it has maintained ever since in the face of a tawdry environment all around.

Though Selfridge was interested in architecture, his primary skills were promotion and selling. These he exploited to the full. There was novelty in the range of goods and services available at Selfridges. New, too, was the scenic artistry of its window displays and its advertisements. Most startling of all, Selfridges started out as a great department store from scratch, instead of building up by stages from a small business, as others had done.

Floristry and plants in 1909 (from a glass slide acquired by the Survey of London)

Reception room in 1909, with portraits of the King and Queen (from a glass slide acquired by the Survey of London)

That involved a level of initial capitalization and borrowing perhaps impossible before 1900. As it turned out, despite the sensation it made and the boost it brought to the west end of Oxford Street, Selfridges was never as profitable as its founder claimed. After decades of risky expansion financed by borrowing, Selfridge was forced out of the driving seat in the 1930s. But by then his ebullience had ensured the completion of Oxford Street’s grandest store – and the equal to any in Paris, New York or Chicago.

By January 1915 Selfridge had hired Sir John Burnet to complete the store. This involved extending the existing plan and front to cover the whole Duke Street to Orchard Street block, stretching back to Somerset Street. Burnet was an architect of standing, with offices at this stage of his career in both Glasgow and London, and having recently been knighted for his King Edward VII Galleries at the British Museum. Burnet may have been tempted by the allure of building a great dome or tower. That, Selfridge now for the first time held out as the crowning feature of his store, set at the back behind the future central entrance.

Early sketch elevations by Burnet suggest domes of octagonal shape, Renaissance or Wren-like in derivation and topped off at over 300ft, in other words well over twice the height of the existing Selfridges parapet, with four flanking tourelles of lower height at the corners. The clearest drawing dates from May 1915 and carries a note that a height of 350ft was agreed with the LCC in March 1916. So the dome project had then gone beyond something cooked up privately between client and architect. Selfridge also at various stages invited alternative ideas for the dome or tower unconnected with the Burnet firm, obtaining designs from Graham Burnham & Co. (the successor firm to D. H. Burnham & Co., before it became Graham, Anderson, Probst & White), Philip Tilden and Albert D. Millar.

Selfridges, ground-floor plan of Oxford Street block as proposed for completion by Sir John Burnet & Tait, 1919 (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

But by 1920 the Burnet firm had reasserted aesthetic control over the whole extension project, including the tower or dome. Thomas Tait had been taken into full partnership with Burnet at the end of the war. Under his aegis the scheme became fixed in principle around 1919 as a tall tower over an enclosed dome, with flanking corner features as before. The details of the tower were to undergo many further changes, but the dimensions of the dome may well have been determined around this time, as certainly was the outline design of the central entrance from Oxford Street. William Reid Dick received a definite contract to design bronze sculpture for this entrance in 1919, and it is likely that Burnet & Tait’s other artistic coadjutors for the whole centre of the building were also agreed with at the same time. However, not until 1923 do the Selfridge & Co. minute books note who they were to be: Reid Dick, Henry Poole and Gilbert Bayes were then to share the sculptural honours with the lesser-known Ernest Gillick. A fifth name is appended, that of the famous Frank Brangwyn; his name was given to the press in March 1923 as someone who was to work on the interior of the extension then about to be started, but his commission soon resolved itself into that of decorating the dome.

Long view of the final model showing the proposed tower to designs by Tait, c.1925–6 (Historic England Archive, AL0140/010/01)

Around 1925–6 Tait made a striking final series of designs in order to finalize the tower itself. Unquestionably, the tower had become a serious ambition and remained so up to the completion in 1928 of the central Oxford Street entrance, which was conceived as a prelude to the dome. Why then was it never built? Such fleeting remarks as there are blame the failure on the LCC, some alleging that the foundations of the tower were feared to threaten the Central Line beneath. But there were other obstacles. The proposed site of the tower lay exactly on the dividing line between the Hope–Edwardes and Portman freeholds. It transpires from the Portman Estate minutes of 1920 that in order to facilitate matters Selfridge had agreed to convey his own share of the tower site to the Portmans but had encountered ‘difficulties’. Seemingly these were never resolved. In the absence of further official memoranda or press references, it seems wiser to assume that the decline of Gordon Selfridge’s financial fortunes from the time he took over Whiteleys in 1927 put paid to the tower. His grand visions continued unabashed, but they never came as close to realization, and after the recession of the early 1930s set in, they became implausible.

Block plan of the Selfridges site (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

In parallel with the fluctuating designs for the dome and tower went the practical task of completing the Oxford Street block. This Selfridge entrusted in 1918 not to Burnet & Tait, consultants only for the overall architectural design, but to the Chicago firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White and their ‘London manager’, Albert D. Millar. The ‘Second Operation’, as it was called, consisted of extending Selfridges over the whole of the former Thomas Lloyd sites. It fell into two parts, the north-west section (Orchard Street and Somerset Street) in 1919–22, followed by the south-west section (Orchard Street and Oxford Street) in 1923–4. The builders throughout were F. D. Huntington Ltd, the successor to the Waring-White Company, which had been dissolved in 1911.

A Cyril Farey perspective of 1923 shows the great Oxford Street front all but complete, with a few little houses in the centre, sandwiched and almost crushed by the east and west wings on either side of them and awaiting demolition for the great entrance and tower. When it came to the point, the tower was not affordable. So Tait had to concentrate his energies on the embellishment of the central entrance itself and the hall behind. The outline of this frontispiece, with its noble portico and wider spacing of the two free-standing columns, probably goes back to Burnet’s first ideas of 1915, while we know that the design had developed far enough for Reid Dick to be commissioned in 1919 to design sculpture for the loggia (as the space behind the columns was called).

Selfridges, front in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

This centre composition, built as Selfridges’ ‘Third Operation’ in 1927–8, became the remarkable climax of the Oxford Street block. The notable feature of the operation was the orchestration of the many artists and craftsmen who had been promised work on the store to produce a masterpiece of decorative arts and crafts, blending older Beaux-Arts traditions of architectural sculpture and metalwork with the zestful brio of the Paris Arts Décoratifs Exhibition of 1925. The overall composition was doubtless Tait’s, probably worked out with the assistance of his trusted assistant A. D. Bryce. But there are many hints of Millar’s attention to details of proportion and arrangement.

Main entrance of Selfridges in 2018, showing bronze doors and flanking figures of Art and Science by William Reid Dick, sculptor, 1929 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

As regards the loggia, the primary artist was Reid Dick, who furnished not only the full-length flanking figures of Art and Science at either end of the doors but the reliefs of putti that frame the great window, engaged in lively endeavours and pursuits. All these were in bronze, cast by the A. B. Burton foundry at Thames Ditton. Also of bronze were the standard lamps in front of the doors, supplied by Walter Gilbert, and the door frames themselves, enriched by George Alexander. Present, too, at the time of opening was the sleek and colourful entrance canopy or marquise, 68ft long and designed by the French metalworker Edgar Brandt, who had made his international reputation at the 1925 exhibition. It was originally illuminated at night.

The figure of Science by Reid Dick, sculptor, 1929 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

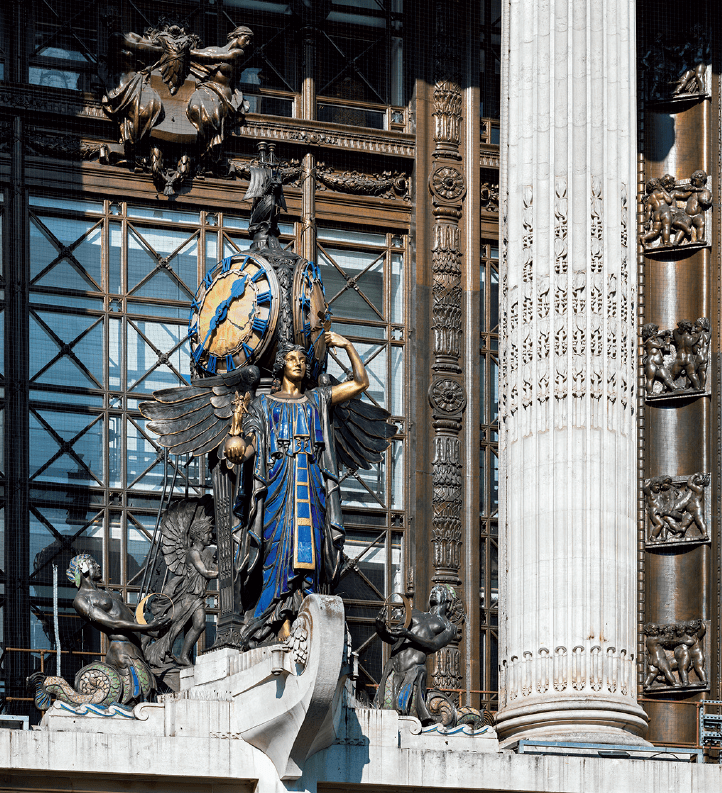

The central feature, the celebrated Queen of Time, in gilt bronze with faience, stoneware and mosaic accoutrements, seems to have been an afterthought. Commissioned from Gilbert Bayes only in 1930, it was installed above the central door in October of the following year. It strikes a sentimental note at odds with Dick’s contributions. Surmounted on a ship’s prow and attended by nereids representing the tides and winged figures representing the hours, the golden queen holds an orb with a figure symbolizing Progress in her right hand while raising an olive branch in her left. Behind her rises an enormous globular clock with two faces surmounted by a further merchant ship. At an upper stage between parapet and lintel stands a single plain bell made by Gillett & Johnston.

Queen of Time figure above the entrance of Selfridges in 2018. Gilbert Bayes, sculptor, 1931 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

After Selfridges the grid plan, the frame construction and the classical frontage with tiers of windows became standard for department stores up to about 1930 – minus the prototype’s costly monumentality. The rebuilding of the Bourne & Hollingsworth front, undertaken in 1925–8, is typical of the genre.

To read the Survey’s full account of Selfridges (the original building and later extensions), please visit our website to access the draft text for Chapter 10.

The former ‘Colonial House’, 17 Leman Street, Whitechapel

By Survey of London, on 23 October 2020

In the nineteenth century, East London was referred to as the Deutsche Kolonie by the German community and ‘our London ghetto’ by the Jewish community. For British sociologist Michael Banton, by 1955 Stepney could comfortably be regarded as ‘The Coloured Quarter’, its identification as a centre for post-war Afro-Caribbean settlement coming under wider public scrutiny as a result of regular letters in the national press criticising government authorities for inaction in the provision of housing.

A number of groups commissioned surveys which aimed to assess the welfare and living conditions of the East End’s Black community, concerned about issues of segregation in the built environment and acutely aware of the dangers of ‘ghettoization’. The experience of the unofficial ‘colour bar’ on resident Black seamen was of especial interest in these studies. During the Second World War and afterwards, Britain politicians did not generally and overtly support segregation. Yet discrimination was by no means absent in British space, and a de facto segregation cut across both private and public urban spaces. Reports suggested that the bar was most evident in port cities like London. For Black seamen in wartime and post-war East London, the existence of a colour bar was indisputable.

From the 1940s, the so-called ‘coloured question’ in London’s East End was a matter of strategic importance for government authorities. The provision of accommodation for seamen was one aspect of this question. Seamen’s hostels had become an issue during the war, responsibility for the ‘special wartime measure’ for seamen from the colonies given over to the Colonial Office, with increasing resources diverted to attend to these men after the Colonial Development and Welfare Act of 1940 was passed. Colonial labour to support the war effort had been actively sought, with recruitment calls made in British colonies in the West Indies and West Africa, yet onshore accommodation for sailors prioritised white British seamen. In an attempt to redress this imbalance, 17 Leman Street, Whitechapel, was acquired by the Colonial Office in 1942 and converted into the only seamen’s hostel for Black men in London. For less than a decade, this small government-sponsored hostel provided thirteen beds for seamen from British colonies in the Caribbean and West Africa.

17 Leman Street in 2007, photograph by Danny McLaughlin, from surveyoflondon.org

The Colonial Office was in fact involved in the establishment of a national network of ‘Colonial Houses’. Whilst often small in scale, seamen’s hostels such as the one in Whitechapel can be seen as flashpoints for discontent as the national identity and rights of Black migrants from British colonies were contested by employers, activists, local and government authorities and the men themselves, against the backdrop of emerging understandings of race relations in the United Kingdom.

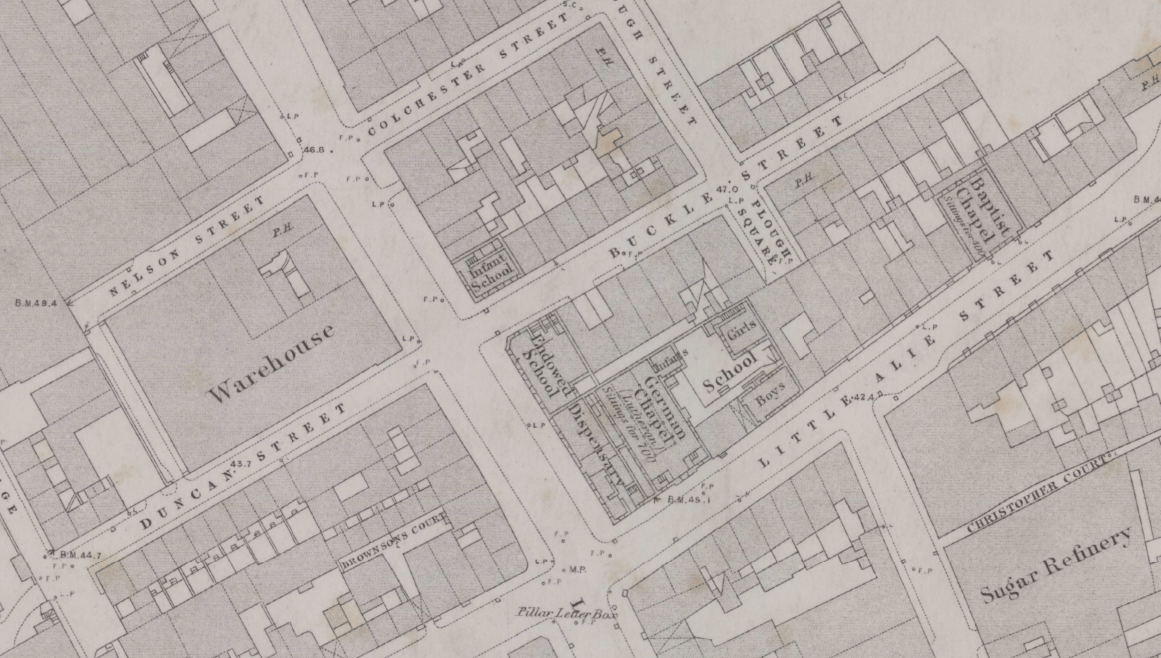

Built in 1861–3 as a German Mission School, the two-storey hostel was situated at the north end of Leman Street, near Whitechapel High Street, until demolition in 2008 to make way for a twenty-three storey tower hotel of short-stay serviced apartments (15–17 Leman Street). Despite functioning for less than a decade as a government-funded hostel that was the subject of some local controversy, Colonial House was well-documented as a result of its connection to the Colonial Office and a group of tireless East London campaigners. Bert Hardy made a series of black-and-white photographs in 1949.

Paternalistic welfare provision for migrant communities was well-established in the Leman Street building long before use as the Colonial House hostel. It was constructed to host education, recreation and acculturation activities for diasporic groups, firstly German Christians and then East European Jews. The German Mission Day School replaced an eighteenth-century tenement and bakery on the site in 1861–3. The purpose-built school was one of a handful of educational buildings clustered on Buckle Street and the east end of Alie Street. This group of buildings was fashioned primarily to serve a large local German population that was closely associated to the sugar-refining business during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The school was designed by Edward Ellis, a London architect better known for his work on offices and warehouses. With a long elevation to Buckle Street and a steeply pitched gable roof, the two-and-a-half storey building assumed an institutional Gothic Revival style, typical of its time. It was formed of London stock brick with black- and red-brick headed arched openings. A large ground-floor corner schoolroom was accessed through decorated double-doors located in a narrow wing extension facing onto Leman Street. An office and further large schoolroom were on the first floor. The top floor provided separate living accommodation for the school’s two teachers. In its unassumingly reserved exterior, the school was matched by other buildings constructed for the local German community, none of which sought to broadcast their ‘alien’ status.

Ordnance Survey map of 1873 showing the infant school at the junction of Leman Street and Buckle Street

By the end of the century, with many German families having moved out of Whitechapel to more salubrious suburbs and many free English schools in operation, leaders concluded that the ‘German Poor School’ should be given up. It closed in 1897 and the schoolhouse was let out for commercial purposes, the rent channelled into funding German education in other parts of the capital.

By 1903 the former school building was in use by the Jewish Working Girls’ Club (JWGC). The purchase of the leasehold was made possible through the support of one individual, (Lady) Julia Henry, daughter of the prominent Jewish-American philanthropist, Leonard Lewisohn. Henry’s support was prompted by an anxiety to show American goodwill towards English Jews in the light of tightening immigration policies in the US, which restricted Jewish movement into the country as religious refugees. The former Mission School was adapted without significant architectural alteration to suit its new purpose by the architect M. E. Collins, who, on completion, reported that the Club contained ‘every accommodation, including the usual recreation rooms, a kitchen, scullery, library and other rooms’. [1] The day-to-day running of the Club was reliant on voluntary contributions and teachers were mostly volunteers from the well-meaning and already settled middle classes, concerned that the assimilation of poor Jewish children from Eastern Europe was occurring neither rapidly nor effectively enough. With 160 girls regularly attending evening and Sunday classes in such subjects as needlework, cooking, Hebrew and religion, singing and drilling in the early 1900s, the Club ‘exceedingly flourish[ed]’ well into the 1920s. [2] The JWGC appears to have continued on until at least the late 1930s before closure around the beginning of the Second World War, the Jewish exodus from East London ‘well-nigh complete’ by the late 1950s.

Requisitioned for use by the War Office soon after the outbreak of war, the former school became a hostel for Black seamen from the British colonies in 1942. In spite of a proliferation of local seamen’s hostels, ‘coloured colonials’ were frequently turned away or were reticent to take up beds reserved for them in larger hostels, aware that their very presence might result in social unrest, as it had in the recent past.

The Colonial Office hostel at Leman Street was intended for thirteen seamen, whose stay was limited to a maximum of three weeks on the basis that they were only temporary residents awaiting their next contract at sea. Accommodation included a basement dining room and kitchen, a ground-floor common room and office, with a large open dormitory, and a small adjoining bedroom on the first floor. The self-contained second-floor flat once home to the German teachers was assigned to the hostel’s warden. Equipped with a billiard table and piano, the common room was intended to serve an important social function, where, it was envisioned, ‘men can sit and talk’. But in the extent of its provision and the effectiveness of its organisation, the small hostel fell woefully short, dogged by problems from its inception and only deepening after the end of the war. Three successive wardens failed to maintain order in the house as men arriving at the hostel often struggled to find places on ships leaving the port, overstayed and grew restless. Although intended only as a place of short-stays for ‘the floating population’, the hostel frequently housed teenage stowaways and those with longer-term ambitions to settle permanently in the country. Local boarding-house keeper Kathleen Wrsama despaired at the lack of support given to these men, who arrived with little or no knowledge of the culture and institutional systems in England. She recalled, ‘The Colonial Office opened a house and you know what it was known as? It was known as the government gambling den. I used to laugh at that. They did nothing for the poor boys’. [3]

Cafés around the west end of Cable Street, often run by former seamen, formed a valuable network of informal social spaces through which private lodging places could be found. A pattern of friendly association brought men into this alternative economy, as former colleagues set up unregistered lodging houses hosting a circuit of friends and friends of friends who arrived after a period of time at sea. Along Cable Street, three-storey bomb-damaged terraced houses in a state of considerable disrepair accommodated cafés on the ground floor, dancing clubs in the basement, and bedrooms on the upper floors. In 1944, thirty-four such humble cafés were identified. African-origin men were the most affected by deficient housing conditions. Derek Bamuta noted, ‘I have reason to suspect that a lot of them actually sleep in bombed out houses’ after having wandered the streets until the early hours of the morning.’ [4] By 1950, those living in unofficial lodgings in the Cable Street area were deemed to be enduring the worst possible conditions. Once settled in temporary accommodation, there were few opportunities for Black tenants to move out of the area; many white landlords would not accept them.

Much to the dismay of local activists such as Edith Ramsay, a councillor, and Father St John Beverley Groser, who saw Colonial House as tokenistic, by 1946 inefficient management of the hostel had caused the Colonial Office to quietly close it only for it to be hastily re-opened soon after. For Ramsay, this episode was evidence of a dereliction of public duty and the abandonment of principles set out in legislation such as the Colonial Development and Welfare Act 1940 which shifted government policy away from a laissez-faire attitude to the colonies and its peoples towards investment in their social, physical and economic needs. The hostel was consistently oversubscribed, with Ramsay reporting that up to forty men could be packed into the building using mattresses on the floor in the mid-1940s. It only catered for a very small percentage of non-resident seamen, and left the needs of the wider resident ‘coloured’ community entirely unattended.

Closure of the tiny Colonial House became representative of what was perceived to be central government’s confused policy and piecemeal approach to the issue of housing British ‘colonials’ in the UK. After a visit to the Leman Street hostel in 1944, a shocked civil servant, Frank de Halpert, exclaimed, ‘Here we are in the greatest city in the world, with the largest colonial empire, and that is the hostel we offer!’ Linking it to a broader political disregard for British territories overseas, he assessed ‘it is on a par with our [political] treatment of the colonies to which in Parliament we devote one or at most two days per annum’. [5]

The London County Council (LCC) also recognised the housing shortage that was affecting growing numbers of Afro-Caribbean men, and particularly seamen, who continued to arrive in the East End. But it held that responsibility to provide suitable hostels for this group lay firmly with the Colonial Office. On the basis that the East End Welfare Advisory Committee would provide essential advice on the running of the hostel, the LCC persuaded the Colonial Office to defer permanent closure of the Leman Street hostel. With the inadequacy of the hostel provision more widely accepted than before, after re-opening discussions turned to consider the construction of a large purpose-built hostel to accommodate approximately 100 men. The bomb-damaged site of St Augustine’s Church on Settles Street was surveyed, as was a property on Wellclose Square, and another on Dock Street, but at the last minute the Colonial Office unexpectedly withdrew its support for the scheme. The existing thirteen-bed hostel muddled on.

Closure of Colonial House was again announced in October 1949. Hopes of a new centre had long since dissipated; blindsided local campaigners felt their considerable efforts to improve conditions had been shamefully undermined. The Colonial Office argued that it had ‘no authority to provide accommodation for colonials permanently resident in the UK and this was primarily a matter for local authorities.’ [6] At this time, while the ‘coloured question’ at last received substantial media attention, the Black population of Stepney had in reality already begun to decline, slowly migrating out of bomb-stricken environments as the demolition of properties earmarked for redevelopment began.

After the Colonial Office’s eventual retreat, in the 1950s the hostel operated briefly under the private management of a West Indian, Donald Watson (or Watkins) of Ladbroke Grove, before transferring to the LCC for use as a reception centre for ‘stowaways’, a scheme partially administered through the London Council of Social Service. By 1959, the centre had closed and the building was used for commercial purposes by H. Bellman & Sons, dressmakers.

The apart-hotel of 2014–16 at 15–17 Leman Street is the glazed slab to the left of centre. Photograph of 2016 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

*This blog post is expanded upon in the article ‘Accounting for the hostel for “coloured colonial” seamen in London’s East End, 1942–1949’ published in a special issue of National Identities on ‘Architecture, Nation, Difference’ (October 2020). The first fifty downloads are free using this link.

1 – Jewish Chronicle, 1 May 1903, p. 22

2 – Jewish Chronicle, 16 March 1923, p. 38

3 – Black Cultural Archives, BCA/5/1/24

4 – Derek Bamuta, ‘Report on an Investigation into conditions of the coloured people in Stepney (1949). Prepared for the Warden of the Bernhard Baron Settlement’, Social Work, January 1950, pp. 387–95

5 – Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archive, P/RAM/3/1/6

6 – Black Cultural Archives, Banton/1

The Mulberry Gardens and the German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface in Whitechapel

By Survey of London, on 18 September 2020

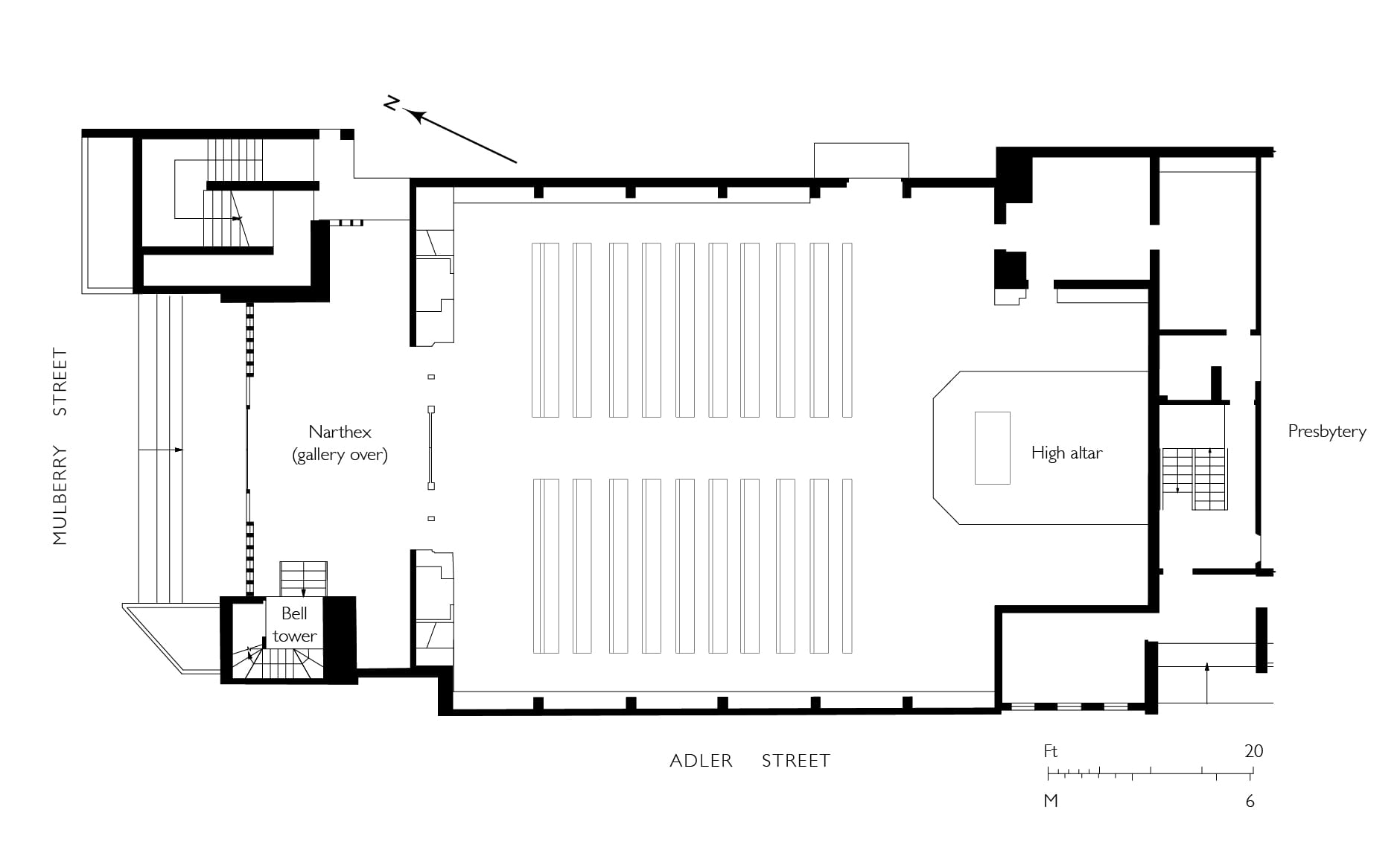

Immediately south-east of Altab Ali Park in Whitechapel is Mulberry Street, a short quiet back street the west end of which is anchored by the strikingly tall bell-tower of the German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, a building of 1959–60. This blogpost presents the church in the context of the longer and previously untold history of its site.

The Mulberry Gardens, south-east of Whitechapel parish church, in the 1740s (extract from John Rocque’s map of London of 1746, courtesy of Layers of London and The British Library)

An approximately four-acre quadrilateral of ground lying south of present-day Mulberry Street was a mulberry plantation, laid out with paths in a grid. Mulberries had been introduced to London by the Romans and were commonly used for making medieval ‘murrey’ (sweet pottage) as well as for medicinal purposes, but there is no basis here for supposing such early origins. The neatly planned grove may have arisen from James I’s attempt to establish native silk production in 1607–9 when around 10,000 saplings were imported and distributed by William Stallenge and François Verton through local officials at six shillings for a hundred plants, less for packets of seeds. Mulberry gardens thus came about across England, echoes of the King’s own of four acres in the grounds of St James’s Palace. The commercial project failed, black mulberries (Morus nigra) having been acquired rather than the white (Morus alba) that silkworms tend to favour, somewhat mysteriously as this choice cannot have been made in ignorance. There was a second mulberry garden close by, across Whitechapel Road in Mile End New Town, north of what is now Old Montague Street and east of Greatorex (formerly Great Garden) Street. Land to the east of that south of Old Montague Street appears also to have been similarly planted. Spitalfields was already at the beginning of the seventeenth century a centre of silk throwing and weaving. Peter Coles has written a history of London’s mulberries.

Whitechapel’s so-designated mulberry garden, like that at the palace, eventually fell to use as a pleasure ground. But there was an intervening period of use as a market garden. Around 1679, Giles Kinchin, a Ratcliff gardener, appears to have been granted a lease of the property by Stepney manor. John Martyr, an apprentice who married Kinchin’s widow, Ann, in 1705 succeeded as the site’s proprietor. The property passed to stepson William Kinchin in 1723, but the gardening venture failed and in 1728 the younger Kinchin’s brother-in-law Rowland Stagg took over, thereafter adapting the premises to be a pleasure ground. There was a garden house near the north end and recreational use continued up to at least 1760, when the arrest of four young gamblers by Sir John Fielding’s runners was indicative of anxieties about the presence of vice. An executed pirate refused burial elsewhere was interred in the otherwise disused grounds in 1762.

Engraved view of the encampment of German refugees in the Mulberry Gardens in 1764 (courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives)

The Mulberry Garden ‘behind Whitechapel Church’ was made new use of for a few weeks in late 1764 as a temporary asylum, a tented camp for around 400 deceived and destitute refugees from the Palatinate and Bohemia who had been abandoned on what they had undertaken as a journey to Nova Scotia. Helped by exhortations to charity and by local people, notably other Germans, in particular the Rev. Dr Gustav Anton Wachsel, the first pastor at the German Lutheran Church of St George on Alie Street, the refugees were able after all to depart and, following a petition to King George III, to settle in South Carolina. The garden remained untenanted until 1772 when John Holloway, a Goodman’s Fields cooper, acquired freehold possession of the property and adjoining lands (about 4.5 acres in all) from Stepney manor for building.

The former Mulberry Gardens as built up from 1784 (extract from Richard Horwood’s map of London of 1799, courtesy of Layers of London and The British Library)

Under Holloway’s ownership streets were laid out from 1784 with more than 150 humble two- and three-storey houses, up by the 1790s on leases of from sixty-one to eighty-one years. Union Street was formed as a widening and continuation of Windmill Alley, a passage from Whitechapel Road. What had been a rope walk to the east became Plumber’s Row, probably because a property at the north end of its west side pertained to Alderman Sir William Plomer. Great Holloway Street and Little Holloway Street ran east–west roughly on the present line of Coke Street, and Mulberry Street crossed as what is now Weyhill Road continuing north to a small open space that John Prier laid out as Sion Square in 1788–9. The Mulberry Tree public house stood on the north side of Little Holloway Street where greater density was interposed with the formation from 1788 of Chapel Court between Union Street and Mulberry Street; that finished up in the twentieth century as Synagogue Place. Holloway’s estate as a whole was sold off at auction in 1839.

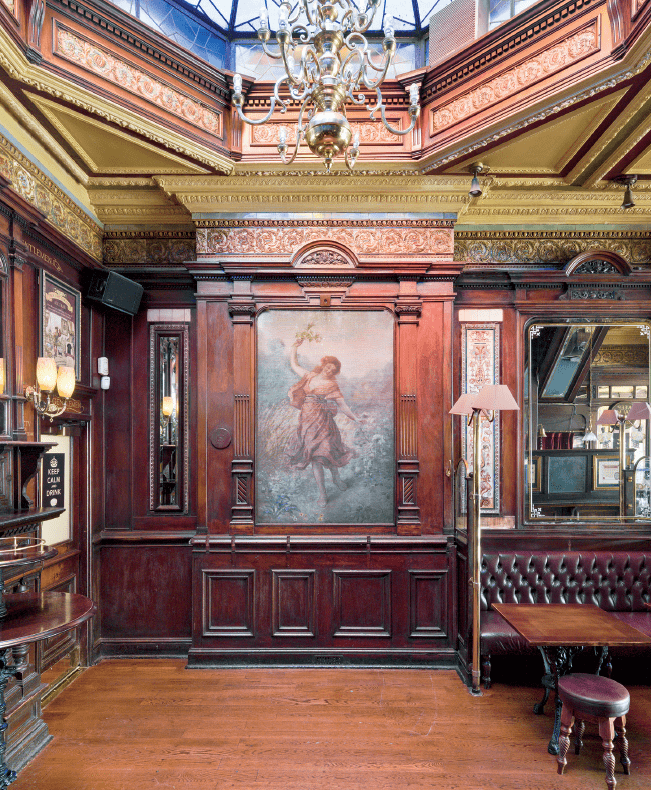

Sion and Chapel as place names in the late 1780s have their explanation in the early adaptation of an attempt to sustain the allures of the locality as a pleasure ground. A large site on the east side of Union Street, 100ft by 160ft, was taken in June 1785 on an eighty-one year lease by George Jones, a ‘riding master’, in partnership with James Jones. The Joneses built premises that were a riding school by day and an entertainment venue in the evenings. These opened in April 1786 as Jones’s Equestrian Amphitheatre, an almost circular polygon of about 100ft diameter with galleries on a ring of columns for a capacity audience of 3,000 under a copper-covered dome. The venue incorporated scenery and machinery, and its ceiling was decorated with ‘painted palm-trees and other forms’. [1] Shows at this early circus displayed ‘a great variety of incomparable horsemanship, and various other feats of manly activity’. [2] With William Parker, George Jones also held leases on the north side of Union Row (present-day Mulberry Street) including the Union Flag public house. Across Union Street a six-house quasi-crescent mirrored the amphitheatre’s shape. The circus venture folded in April 1788, perhaps on account of licensing difficulties, with a send-off that included non-equestrian acts from Sadler’s Wells and Philip Astley’s Royal Grove. Astley’s Riding School and Charles Hughes’s rival Royal Circus, Equestrian and Philharmonic Academy, both close to Westminster Bridge on the Surrey side, had probably inspired if not actually produced the Joneses in the first place.

At its closure the amphitheatre had been let for conversion to use as a chapel for the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Founded in 1783 as a dissenting denomination, the Connexion had already converted another circular pleasure pavilion, the Spa Fields Pantheon in Clerkenwell. In 1790 the Union Street building became the Sion (or Zion) Methodist Chapel, a stronghold of Calvinistic Methodism that had its own school.

London’s German Catholic Mission acquired Lady Huntingdon’s Sion Chapel in 1861. This congregation, unique in England, had its origins in 1808 at the Virginia Street Chapel, just south of Whitechapel in Wapping. There were thousands of German Catholics in the area, largely employed in sugar refining. A year later the mission moved to premises in the City that were dedicated to SS Peter and Boniface, the last appropriate as having gone to Germany as an English missionary (born Wynfrid).

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, interior of the building of 1873–5, as extended in 1882, photographed c.1900 (courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives)

In 1862 the former circus building was given a thorough refit in a Romanesque style, work overseen by F. Sang that included an 18ft-wide Caen stone altar. At the opening the Rev. Dr Henry Edward Manning preached and Cardinal Wiseman blessed the church. A section of the building east of the amphitheatre was adapted for the mission’s school in 1870–1. Then, in May 1873, the old theatre suffered a spectacular collapse of its domical ceiling and had to be cleared. Manning helped Father Victor Fick raise funds for a replacement building. A German Gothic scheme by E. W. Pugin (who had prepared plans for a building for the Mission in 1859–60) was superseded by a loosely Romanesque design from John Young, that style preferred by Manning who attended the opening in 1875. In front of a basilican brick church, a square west tower bore Royal Arms, an overt proclamation of loyalty, and came to incorporate a mosaic of 1887 showing St Boniface preaching. Set back from the street, the church was gradually enclosed by later brick structures by Young in a similar manner. There was the addition of a presbytery to the south in 1877, a northern school range in 1879, and eastwards extension of the church with an apse and enhanced interior decoration in 1882, this carried through by Father Henry Volk and justified on the grounds of a growing immigrant congregation. Stained-glass windows and wooden Stations of the Cross were of German origin. There were further works in 1885, when bells made at the neighbouring Whitechapel Bell Foundry were added to the tower. In 1897 Father Joseph Verres gained approval for the formation of a covered playground below a schoolroom and sanitary block to the north-east. More improvements and an extension of this block followed in 1907–8 and 1912–13.

Dispersal and expulsion of members of the congregation aside, St Boniface suffered heavily the consequences of Britain’s wars with Germany. Damaged in a Zeppelin raid in 1917 and having been confiscated as enemy property, the church passed in 1919 into the ownership of the Catholic Archdiocese of Westminster. Consecration followed in 1925 when Father Joseph Simml was installed as priest. Then a high-explosive bomb destroyed the church in September 1940. Simml, an opponent of Fascism, stayed through the war, sometimes preaching in the open air. The congregation retreated to the easterly school buildings.

Rebuilding was pursued after the war despite the loss of much of what had been left of the congregation to more salubrious parts of London. Some remained willing to travel to Whitechapel, and from 1949 there were also new immigrants, predominantly women, many from East Germany drawn to work in factories, hospitals and homes, for education or through marriage, sometimes to British soldiers of the post-war occupation. Some German prisoners of war also stayed on. War-damage assessment was handled for the Archdiocese by Plaskett Marshall & Son, architects, who prepared a conservatively historicist scheme for a new church in 1947. Without funding this was premature, but on archdiocesan advice the firm was kept on. Upon the death of the senior partner, his son, Donald Plaskett Marshall, took control through Plaskett Marshall & Partners; he worked extensively for the Roman Catholic Church in its London diocese in the 1950s.

Model for the rebuilding of the Church of St Boniface to designs by Toni Hermanns, as displayed in 1954 (photograph courtesy of TU Dortmund, Baukunstarchiv NRW) and as surviving (photograph courtesy of the parish of St Boniface)

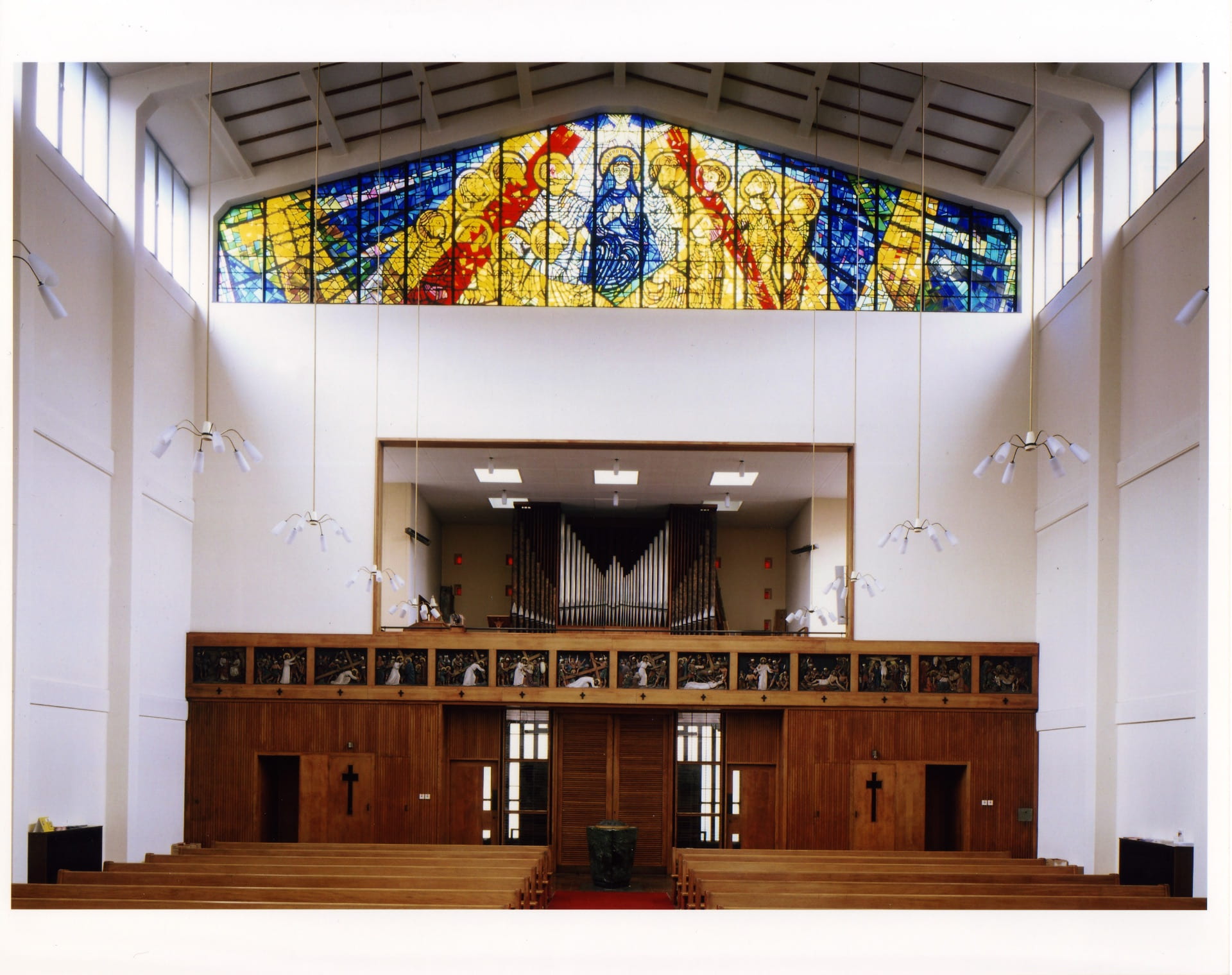

From 1952 the rebuilding was pursued by Father Felix Leushacke (1913–1997), thinking big in anticipation of future growth and working with Simml, who brought a liking for Bavarian Baroque to the project. Alongside war-damage compensation there was to be financial help from the West German government. The first plans for the new building disappointed Leushacke so in 1954 he involved a German architect and friend, Toni Hermanns of Cleves (Leushacke’s birthplace). Hermanns visited the site, prepared numerous possibilities in sketches and then presented worked-up plans and a model that were photographed and published. The model and preliminary sketches survive at the church. Hermanns, a strongly imaginative architect best known for the Liebfrauenkirche in Duisburg of 1958–60, proposed a cuboid block, to be lit by numerous small round windows in a radiating pattern on a long west (liturgical south) elevation. The Archdiocese vetoed the scheme – Leushacke quoted its response as ‘Never!’, upon which Plaskett Marshall said (an assertion that he was to remain in control in Leushacke’s view), ‘And now you leave the dirty work to me!’ [3] Plaskett Marshall worked up revised plans in close if fraught consultation with Leushacke in 1955–6, encountering many more objections from Bishop George Craven at Westminster. The scheme was settled with approval from the newly installed Archbishop William Godfrey in 1957 after debate over the cubic or auditory nature of the main space, progressively non-processional for a Catholic congregation at this date. Higgs & Hill Ltd undertook construction beginning in November 1959 and the new Church of St Boniface opened in November 1960, Cardinal Godfrey being present at both the start of work and the opening. A building of some architectural panache, the Church of St Boniface is unlike other work by Plaskett Marshall and does seem in significant measure to reflect Hermanns’s approach and aesthetic, though Hermanns was not involved after 1954. Wynfrid House, a guest house of 1968–70 adjoining to the east and also by Plaskett Marshall, supplies a telling comparison.

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, Mulberry Street, Whitechapel, in 2003 (photograph by Jonathan Bailey for English Heritage, © Historic England Archive) and ground plan (drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London)

The church has a concrete encased steel portal-frame structure. The main walls are of hand-made dark-brown bricks rising to a clerestorey. Above, concrete eaves, cast (unusually) on plastic-lined shuttering for a coffered effect, underlie a copper roof that was supplied by the Ruberoid Co. Ltd. The upper-storey of a Westwerk is faced with small coloured-glass windows in a grid of black mosaic crosses on a yellow ground. The south-west tower rises 130ft and is clad with concrete slabs faced with grey-scale patterning in ceramic mosaics. At its top an open belfry houses the salvaged locally made Victorian bells. This slender and prominent landmark tower was chosen in an either-or situation in preference to central heating, toilets and a vestry room, prestige trumping comfort. The building as a whole is remarkable for the richness, originality and elegance of its decoration. The plain three-storey presbytery to the south facing Adler Street, habitable by 1962, contrasts with ochre two-inch bricks.

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, interior views in 2003, showing the south (liturgical east) end (top), and north (liturgical west) end (bottom) (photographs by Jonathan Bailey for English Heritage, © Historic England Archive)

The church interior is spacious and light, generally white in its surfaces setting off fittings and stained glass of distinction. Within a timber-lined narthex, it provided seatings for 200 in the nave and sixty in a north gallery. The high altar, Lady Altar, tabernacle plinth, and a quasi-triangular font are all of a dark green marble, with a chancel floor of white Sicilian marble, enlarged after the Second Vatican Council of 1962–5. On the south (liturgical east) wall there is a large sgrafitto mural of Christ in Glory above St Boniface preaching to the faithful, made by Heribert Reul of Kevelaer, which is near Cleves. Figurative and decorative wrought iron is by Reginald Lloyd of Bideford, Devon – four panels (altar rails resited as a kind of reredos in the post-Vatican II reordering of the sanctuary) and a gallery front depicting the Crucifixion with the Nativity and the Resurrection. An ambo or pulpit front depicting the parable of the sower has been removed since 2003. There is a lectern of 1980, made by Lloyd to mark the thirteenth centenary of St Boniface’s birth in Devon. The font has a bronze cover commemorating Simml (d. 1976), also by Reul. To the north (liturgical west) the gallery front has the Stations of the Cross, relief carvings from Oberammergau (by Georg Lang selig Erben), eleven of fourteen dating from 1912 and reused from the old church. Romanus Seifert & Sohn made the organ in 1965. A spectacular stained-glass window by Lloyd above the gallery depicts Pentecost. The congregation began to disperse and dwindle and since the 1970s the church has been shared with a Maltese community.

1 – The Builder, 4 October 1862, p. 713

2 – Morning Herald, 20 April 1786

3 – Felix Leushacke, ‘Memorandum über Damalige Umstände beim Wiederaufbau des Anwesens der deutschen katholischen Mission in den Jahren 1958/60 für St Bonifatius-Kirche und Pfarrhaus und 1968/70 für das Gemeindezentrum Wynfrid-Haus in London Whitechapel’, 1993, typescript held in the parish archive at the Church of St Boniface, p. 3

Will the real J. T. Parkinson please stand up? The architect of Bryanston and Montagu Squares in Marylebone

By Survey of London, on 21 August 2020

Long, narrow, leafy, and still to a large degree lined with elegant late-Georgian terraces of the 1800s–20s, Bryanston and Montagu Squares form a distinctive part of the grid of streets and squares making up the Portman Estate district of St Marylebone, south of Marylebone Road. While the aristocratic mansions of nearby Portman Square have almost all vanished, replaced before the Second World War by blocks of flats, the smaller scale of these two charming squares has helped ensure their survival, most of the losses there being the result of wartime bombing. Like many terraces of the day, the houses on the long sides of Bryanston Square were designed as complete Classical compositions, with pilastered end pavilions and centrepieces. Those in Montagu Square are plainer but more informal, with shallow bow windows on the ground floor, many of these carried up higher later on in the nineteenth century.

East side of Bryanston Square, looking south-east (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The architectural and town-planning qualities of these squares have long been recognized, but the architect who designed them, James Thompson Parkinson (d. 1859), has rarely been correctly acknowledged. Most sources, even some of the most reputable, attribute the work to the apparently unrelated architect and surveyor Joseph Parkinson (d. 1855). Other aspects of the two men’s careers have often been misidentified or conflated, and the confusion has even created a hybrid, Frankenstein’s monster of an architect, ‘Joseph T. Parkinson’, who never existed. This blog post attempts to disentangle the two Parkinsons, setting out their respective identities and some of their major commissions.

East side of Bryanston Square, looking north-east (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

James Thompson Parkinson was born in 1780 in Whitechapel to John Parkinson, a surgeon dentist, and his wife Elizabeth. The family moved to central London in 1787 or 1788, to Racquet Court, Fleet Street, an address which James sometimes used for his practice and where two of his brothers carried on their father’s business after his death in 1804. Howard Colvin, who attempted to separate the two Parkinsons and their work in his Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, records that J. T. Parkinson was apprenticed in 1795 to Richard Wooding (d. 1808), a London surveyor, and he seems to have been in practice on his own by the early 1800s. In 1805 he married Louisa Sophia Salter of Poplar at St Pancras Old Church. By this time he was based in Ely Place in Holborn.

In the Auto-Biography of an Octogenarian Architect (1870), George Ledwell Taylor recalled being articled in 1804, aged 15, to ‘Mr Parkinson of Ely Place’, having been passed on to him by the well-known architect-builder James Burton, who was then about to retire. Taylor gives little information about his employer, but does recount that he was a commander of the 1,000-strong volunteers corps raised by Burton in 1804, the Loyal British Artificers. Parkinson was involved with Burton in property development in the Tavistock Square area of Bloomsbury in the early 1800s, where both men lived, and he handled the sale of Tavistock House when Burton left there for a new country house, Mabledon House, that he built in 1805 near Tonbridge in Kent. For these reasons, it seems most likely that it was J. T. Parkinson who designed Mabledon House for Burton, not Joseph Parkinson, to whom it has often been attributed.

Mabledon House, near Tonbridge, Kent. Engraving by G. Cooke (from a drawing by J. C. Smith), c.1807. From J. Britton’s The Beauties of England and Wales (1801–15)

Marylebone was where J. T. Parkinson’s energies were to be concentrated in the ensuing decades. For some years he was architect and surveyor to the Portman Estate, which until the 1950s, when sales took place to meet death duties, extended from Oxford Street to well north of Marylebone Road. During this period he was working in partnership with David Porter, a chimney-sweep who built up a successful business from next to nothing and became a property developer and notable philanthropist. Much of the southern portion of the Portman Estate had already been built up by this time, but there remained a good deal of undeveloped ground ripe for building, and as well as Bryanston and Montagu Squares, Parkinson and Porter were engaged in development elsewhere on the estate during the 1810s–30s, including the Dorset Square area north of Marylebone Road. Parkinson also designed the new part-covered Portman Market for hay, fruit, vegetables, meat, and also pigs, erected in 1829–30 in Church Street off Edgware Road. Run by the agent to the Portman Estate, Thomas Wilson, the Portman Market was set up to match or eclipse Covent Garden, but never achieved this level of success. It was damaged by fire in the 1880s and subsequently rebuilt, and although the site has now been redeveloped, the market itself lives on in the form of the regular open-air market in Church Street, with stalls stretching from Edgware Road to Lisson Grove.

Montagu Square and environs, c.1870 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

One other identifiable work by J. T. Parkinson from this period is a chapel built by subscription at Bagshot Heath, Surrey, in 1819–21 (with the assistance of a small grant from the recently formed Incorporated Church Building Society), for which a plan and elevation by him survive at Lambeth Palace Library. But little else is heard of Parkinson after around 1830 until his death. Colvin suggests that in the 1830s Parkinson left London for Jersey, and it is possible that he spent the latter part of his life there and on the Continent. When he died in December 1859, at the house of his nieces in Holloway, aged 79, it was reported that he had latterly been ‘of Versailles’ as well as of Wyndham Place on the Portman Estate. A son, Rawlinson Parkinson (d. 1885), followed him into the architectural profession, and continued to use the Racquet Court, Fleet Street address for his practice. He was a resident of Highgate, and surveyor to Hornsey District Council, and buildings designed by him include: Fairlawns, a large classical villa of 1853 at 89 Wimbledon Park Side, Putney Heath; the Rainbow Tavern at 15 Fleet Street (1859–60); and new printing offices for the Standard newspaper in Shoe Lane (1871).

J. T. Parkinson’s pupils include the architect and civil engineer Edward Cresy (1792–1858), friend, travelling companion, brother-in-law and co-author of George Ledwell Taylor.

Fairlawns, 89 Wimbledon Park Side, Putney Heath (© Historic England Archive, IOE01/04345/22)

Joseph Parkinson was born in 1783, the son of James Parkinson (d. 1813), a land agent. A year after Joseph’s birth, his father acquired the well-known natural history collection of Sir Asthon Lever, which Lever had decided to dispose of by lottery. The collection had latterly been displayed by him in a museum at Leicester House, Leicester Square. James Parkinson took a substantial terrace house on the south side of Blackfriars Road, near Blackfriars Bridge, and in 1788–9 erected at its rear a spacious circular exhibition building, known as the Rotunda, to exhibit the Leverian Museum.

Frontage of Leverian Musuem, Blackfriars Road, 1805. Watercolour by V. Davis (Wellcome Collection, shared under an Attribution 4.0 International CC BY 4.0 licence)

Grand Saloon and Gallery in the Rotunda at the Leverian Museum, Blackfriars. Page from William Hone’s Every-Day Books, Vol 2, 1826–7 (© The Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence)