The Langham Hotel

By the Survey of London, on 18 March 2016

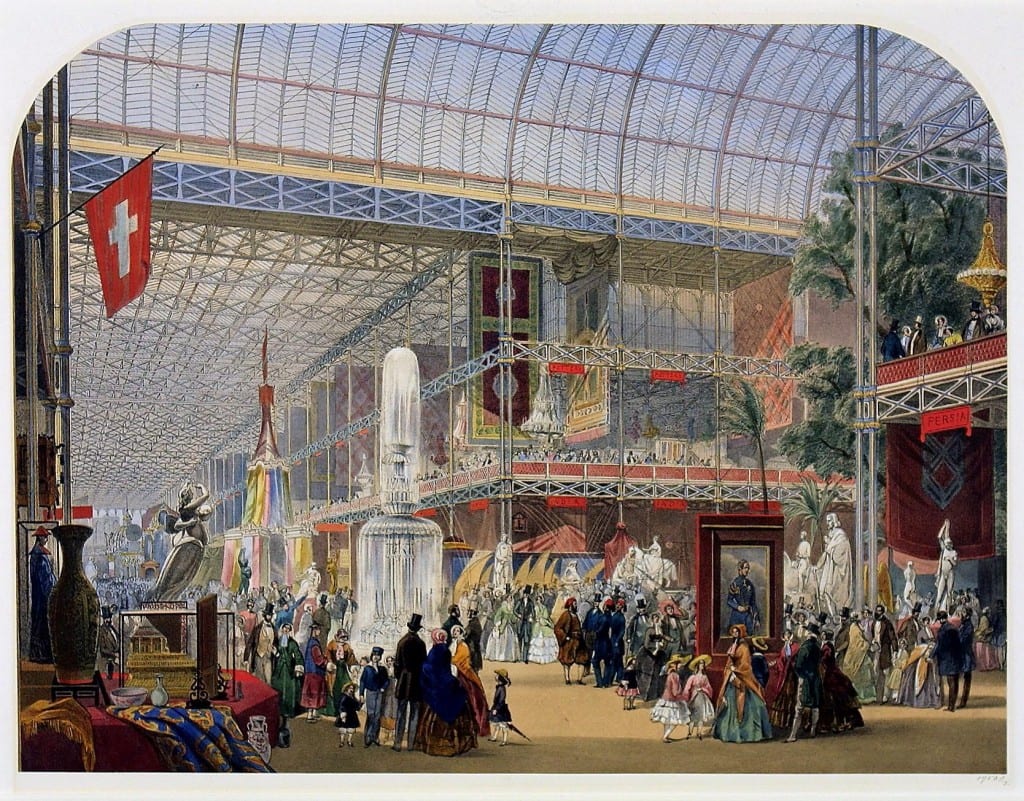

The Langham Hotel of 1863–5 was London’s largest hotel when new, and among London’s largest buildings, a prime example of what were dubbed ‘monster’ hotels, more kindly ‘grand’. Following the railway-station hotel boom of the 1850s the Langham was a significant novelty for being dissociated from a terminus. The Langham Place site in a smart district was thought right for a hotel for its openness, therefore healthfulness. Distance from a railway station could be marketed as a virtue, but this was still a bold speculation that looked to American rather than local precedents.

![The Langham Hotel (by The Langham, London, reproduced with a Creative Commons licence via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)])](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/files/2016/03/Langham-Wikipedia-Commons.jpg)

The Langham Hotel (by The Langham, London, reproduced without changes under a Creative Commons licence via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

The Langham Hotel Company Limited set out to build a hotel ‘on a scale of comfort and magnificence not hitherto attained in London’. [1] Its ‘very respectable’ directors were a solid bunch of mercantile men, headed by two aristocrats stooping to trade – Henry Chetwynd-Talbot, 18th Earl of Shrewsbury and Talbot, as president, William Coutts Keppel, Lord Bury, as vice president. Among the directors was Peter Graham of Jackson & Graham, a high-class Oxford Street furnishing firm. The adjacency of several embassies including the American consulate inspired hope of accommodating diplomats. Imminent completion of the Metropolitan Railway with its station at the top of Great Portland Street would, it was claimed, make up for the absence of a main-line terminus.

A design competition was won by John Giles, a novice architect. He was persuaded to work with the more experienced James Murray, whose designs for the interiors were regarded by the competition committee as especially good – the forced partnership ended up in court over ownership of the drawings. Giles was probably responsible for the floor plan and exterior, Murray for details of the internal layout. Lucas Brothers, who had recently finished the London Bridge Railway Terminus Hotel, were contractors and major shareholders. Jackson & Graham supplied furniture and brought in Owen Jones to design interiors.

The hotel opened in June 1865 with the Prince of Wales and 2,000 others in attendance to see London’s most splendid hotel, spread over ten floors including basements and attics, and overall half again bigger than the Grosvenor Hotel of 1862. It aimed ‘to suit all from princes to the middle-classes’. [2]

The Langham Hotel, drawn from measured survey. Please click to download a pdf version of the drawing (© Survey of London, Helen Jones and Andy Crispe).

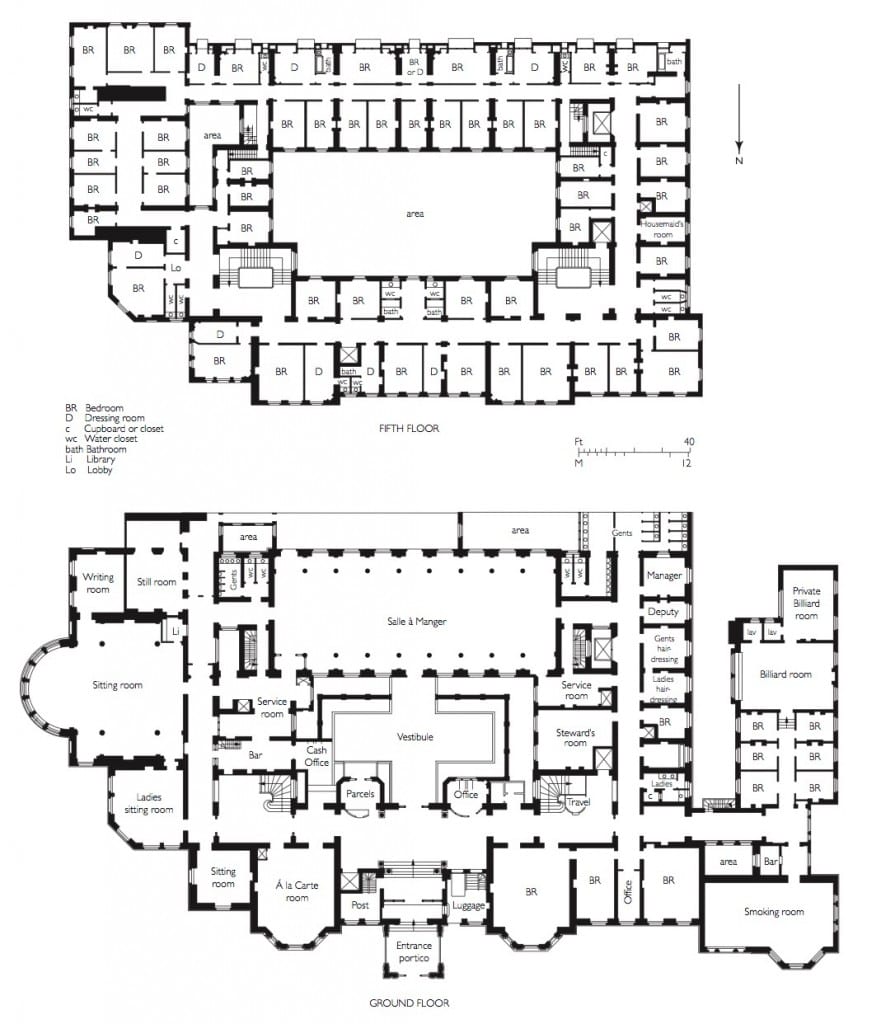

Plans depicting the layouts of the ground and fifth floors of the Langham Hotel in 1907. Please click to download a pdf version (© Survey of London, Helen Jones).

The report of the opening in the Illustrated London News neatly summarizes how the hotel was received:

The style of architecture would be called Italian; it is, however, plain, simple, and substantial, and singularly free from meretricious ornament. It includes large drawing-rooms, a dining-room, or coffee-room, 100 feet in length, smoking-rooms, billiard-rooms, post-office, telegraph-office, parcels-office, &c., thus uniting all the comforts of a club with those of a private home, each set of apartments forming a ‘flat’ complete in itself. Below are spacious kitchen, laundry, &c., and water is laid over all the house, being raised by an engine in the basement. Some idea of the extensive nature of the establishment may be formed when we add that its staff of servants number about two hundred and fifty persons, from the head steward and matron down to the junior kitchenmaid and smallest ‘tiger’. The ‘Langham’, on an emergency, can make up as many as 400 beds. The floors are connected with each other by means of a ‘lift’ which goes up and down at intervals. It is as nearly fire-proof as art can render it. [3]

Giles’s exterior, yellow Suffolk bricks (commonly known as “Suffolk Whites”) with Portland stone dressings, is heavily indebted to the Grosvenor. It is Italianate, but picturesquely so, with consciously eclectic Gothic elements and an eventful skyline with French pavilion roofs. The shape of the site was a gift, allowing, even forcing, some break-up of the cuboid massing to the east, the locus for an asymmetrical parti with a pointily domed tower and a big two-storey bow. The building was praised – ‘The points which call forth admiration are the union of regularity with picturesqueness, so desirable in town architecture; the subordination, at least in the side, of detail to general effect, and the reserve and simplicity which are manifest in a great part of the work.’ [4] Many have since disagreed, but a century later Henry-Russell Hitchcock judged the building ‘a rich and powerfully plastic composition, most skilfully adapted to a special site, and more original than most of what was produced in the sixties in Paris’. [5]

The rich sculpture which adorns the eaves cornice and imposts of the lower-storey window arches (© Survey of London, Derek Kendall, 1988).

The sculptural detail repays close examination. Below the heavy eaves cornice there are griffins and sphinxes, some addossed and seated, others rampant yet bovine, made of moulded cement on slate armatures. Livelier and lither stone-carved creatures, more griffins, lions and lizards, grace the imposts of lower-storey window arches. These ‘semi-Gothic Grotesques’ were harshly judged – ‘Their antics … have an artificial and done-to-order look about them, very different from the grim humour of ancient work.’ [6] Hitchcock, who suspected the influence of Viollet-le-Duc, saw ‘elephantine playfulness’, which seems fairer.

In December 1940, bombing destroyed the building’s north-east corner and, with consequent flooding, the hotel closed. The BBC took up occupation from 1941, using the premises as offices and studios to 1986. Reconversion to hotel use in 1987–91 was by Hilton International.

Reference

[1] Morning Post, 30 June 1862, p. 2

[2] The Times, 12 June 1865, p. 9

[3] Illustrated London News, 8 July 1865, p. 12

[4] Building News, 20 Oct 1865, p. 72

[5] Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architecture, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 1958, p. 16

[6] Building News, 20 Oct 1865, p. 727

Close

Close