What’s a monkey, what’s a primate?

By ucbtcwi, on 8 October 2017

I have something to admit. Before starting my PhD researching the primate gut microbiome, I didn’t completely know the difference between the terms “monkey” and “primate”. Perhaps this is somewhat forgivable given that I was primarily a microbiologist, but I remember still feeling a sort of sneaky shame in googling the differences after I read the project title, like it was something I should definitely know.

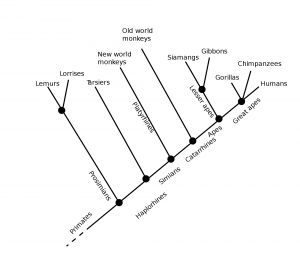

As it turns out, the rules of what’s what in the primate tree are pretty simple once you know them. The evolutionary history of primates can be traced back to between 63 – 74 million years ago (MYA), and as they stand today can be divided into two main branches, named Strepsirrhini and Haplorrhini, which based on molecular studies are hypothesised to have branched away from each other around 64 MYA. Interestingly, the two groups are named after their noses, with Strepsirrhini meaning “wet-nosed” and Haplorrhini meaning “dry-nosed” and were called so by a French naturalist friend of Robert Grant, named Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

A simple primate evolutionary tree showing the major branchings. Strepsirrhini were formerly known colloquially as “prosimians”, although this is an outdated term now. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

Strepsirrhini primates (unsurprisingly) tend to have wet noses, as well as a more pointed, almost dog-like snout rather than the flatter faces of their Haplorrhini cousins, and are thought to be most similar in appearance to the first primates. The clades that make up the Strepsirrhini primates are the lemurs of Madagascar, the lorises from South East Asia and India, and the pottos and galagos (or bushbabies) of Africa. Until recently, tarsiers were also thought to belong to Strepsirrhini, however now they’ve been moved to the sister clade of Haplorrhini.

If you’ve been wondering up to this point where the monkeys are, you need look no further than the Haplorrhines. In terms of number of species, this clade is almost entirely monkeys. The major two branches within this clade are between Catarrhini (meaning “down-nosed”), or Old World monkeys and apes found across Africa and Asia, and Platyrrhini (meaning “flat-nosed”), or New Wold monkeys found in Central and South America.

A map showing the distribution of monkeys across the globe, with Old World monkeys coloured in red and New World monkeys coloured in orange. Licensed under CC0 3.0

Within the catarrhines, the apes, or Hominoidea, comprise gibbons, orang-utans, gorillas, chimpanzees and, of course, us. Apes are thought to have formed their own distinct clade from Old World monkeys (or Cercopithecoidea) around 29MYA, so if you wanted to get really technical, and you were the kind of person who happily accepts birds as being modern day dinosaurs, it wouldn’t be entirely wrong to say that apes are actually monkeys too.

So, hopefully the next time you get stuck wondering whether the primate you’re looking at is a monkey or not, you’ll be a little more clued in.

Close

Close