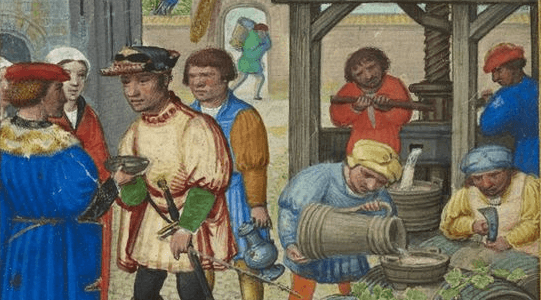

Medieval Calendar Predictions for 2017

By Arendse I Lund, on 16 January 2017

With the twists and turns of 2016, excuse me if I’m not crazy about not wanting to make predictions for the year ahead. Instead, I’ll look back. By relying on some good ol’ advice from the fifteenth-century, I don’t see how anything could go wrong.

Below is my translation from Middle English of the calendar from the Medical Society of London, MS 136; the italicised portions indicate where I have relied on the Middle English text of the Henslow duplicate instead. Remedies 143-156 in this manuscript contain instructions on how to ensure a good year. These contain a month-by-month breakdown and, like a negative fortune cookie, list the bad or “perilous” days to expect each month. Forewarned is forearmed, right?

In the month of January, white wine is good to drink and blood-letting to forbear. There are seven perilous days: January 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 10th, 15th, and 19th.

In the month of February, don’t eat pottage made of hocks because they are poisonous. And bloodlet from the wrist of the hand and the vein of the thumb. There are two perilous days: February 6th and the 7th; the 8th is not that good either. Eat hot meats.

In the month of March, eat figs and raisins and other sweet meats. And don’t bloodlet on the right arm for each manner of fever of that year. There are four perilous days: March 10th, 12th, 16th, and 18th.

In the month of April, bloodlet on the left arm on the 11th day and that year he shall not lose his sight. And on April 3rd, bloodlet and that year you shall not get a headache. Eat fresh flesh and hot meat. There are two perilous days: April 6th and 11th.

In the month of May, arise early and eat and drink early; don’t sleep at noon. Eat hot meats. Don’t eat the head or the feet of any animal because her brain wastes and her marrow consumes, and all living things become feeble in this month. There are four perilous days: May 7th, 15th, 16th, and 20th.

In the month of June, it is good to drink a draught of water every day while fasting; eat and drink meat and ale in moderation. Only bleed when there’s the greatest of needs. There are seven days which are perilous to bloodlet.

In the month of July, keep away from women because your brain is just beginning to gather its humors. And don’t bloodlet. There are two perilous days: July 15th and 19th.

In the month of August, don’t eat wort plants or cabbages and don’t bloodlet. There are two perilous days: August 19th and 20th.

In the month of September, all ripe fruit is good to eat and blood is good to let. Without doubt, he who bloodlets on September 17th shall not suffer from edema, nor frenzy, nor the falling evil.

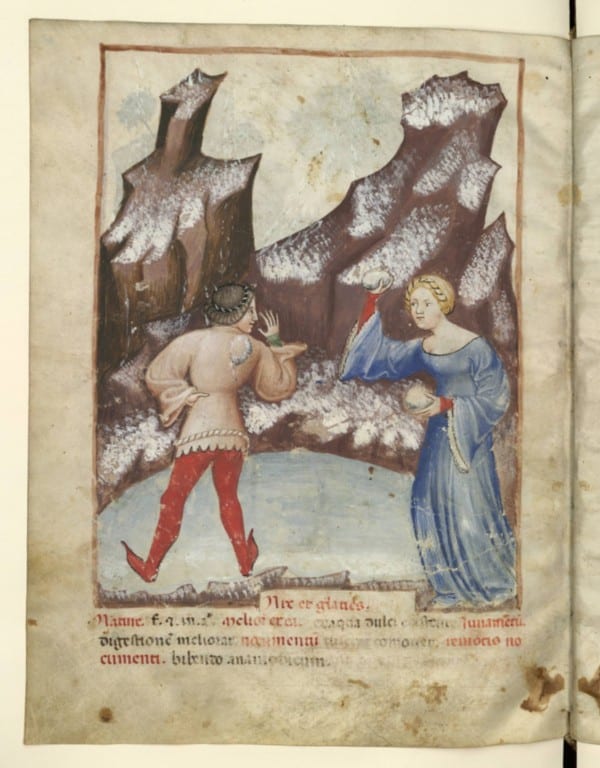

In the month of October, new wine is good to drink, and bloodlet if necessary; there is one perilous day and that is October 6th.

In the month of November, don’t take a bath because blood is gathering well in your head-vein. Apply a cupping glass a little because lancing and cupping are good to use then since all the humors are active and quick. There are two perilous days: November 15th and 20th.

In the month of December, eat hot meats and bloodlet if necessary. There are three perilous days: December 15th, 16th, and 18th. Refrain from cold worts as they are poisonous and melancholic.

Whosoever holds to this life regimen may be secure in his health.

by Arendse Lund

Close

Close