Bodies at work: 3 more interventions that are changing museums

By tcrnkl0, on 22 June 2018

Last time in the Label Detective series, I looked at 3 interventions in museum labelling that dramatically changed the feel and experience of museum objects. But changing a label doesn’t always do the job to address how museums (like all public spaces) have excluded or made invisible certain people, histories, or information.

This time around, I’m highlighting three ongoing efforts that centre people showing up to make a change in museum space. Museums today see themselves not only as places that hold objects, but as dynamic social forums. If museums do want to occupy this role, it means not just getting involved in ‘dialog’, but everything from restitution to wacky, meaningful art invasions.

1. Museums Detox

Museums Detox is a network of black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) museum and heritage professionals. The network does important work creating a supportive space for BAME individuals in the sector and push for real progress on the persistent underemployment of BAME staff in museums, as well as broader issues of inclusion and representation.

One of the simple but significant interventions they’ve done is to visibly get together in museum space. In 2016 their flash mob at the Museum of London received national media attention. In a Museums Association article, Sara Wajid, one the founders of Museum Detox said about the event:

‘We just feel like people don’t realise there are so many of us from BAME backgrounds who work in museums, and when we get together as the Museum Detox group it can often take people back to see a bunch of confident BAME people walking around a gallery. […] It got us thinking about audiences. Why is it weird to see a group of people of colour hanging out at a museum?’

2. Campaign to return the Gweagal Shield

The repatriation of artefacts taken by the British government and collectors during colonisation, or violent and exploitative relations is an ongoing issue. Although in many publicised cases, like that of the Parthenon Marbles, repatriation depicted is a government-to-government process, individuals and non-state communities also play important roles advocating for the return of materials.

The Gweagal Shield is a sacred Aboriginal shield taken by the British at the beginning of their violent conquest of Australia at the end of the 18th century. Upon seeing on display for the first time, Rodney Kelly, a descendant of one of the aboriginal warriors shot at by Lieutenant James Cook on his landing in Australia, recognised the importance of the cultural and community work it could do for the contemporary Gweagal people.

Kelly has since twice come to the England to formally request the shield’s repatriation, in addition to other Aboriginal artifacts held by British and European institutions from that period. Kelly has also spent time in the gallery where the shield is held sharing alternative histories of the shield and hold ‘rebel lecture’ events, including one in partnership with the next group of museum interventionists below!

Rodney Kelly giving a rebel lecture on the Gweagal Shield with BP or not BP? in 2017. Photo Credit: Anna Branthwaite via Art Not Oil Coalition

The campaign to return the Gweagal Shield is also a good example of how object labels can be used to cover up as well as illuminate. In May 2018, Dr Sarah Keenan, a legal scholar, argued that British Museum’s recent changes to the shield’s label text function to weaken the repatriation claims being made.

3. BP or not BP?

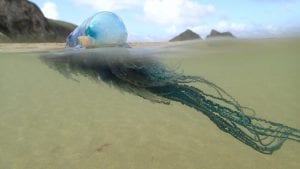

BP or not BP? is a theatrical protest group that campaigns for museums, galleries, and other arts and cultural institutions to drop sponsorship deals with oil companies. BP or not BP? argue that oil companies, including BP, play a major role in contributing to climate change and the destruction of environments and frontline communities around the world.

One of the things that make their protests and interventions noteworthy is how they use what we might call the grammar of museums and art institutions to speak to them in their own language. Many of BP or not BP? actions dedicate huge effort to creating art installations or even whole exhibitions so striking that sometimes visitors don’t realise they’re not the work of the museum itself.

In all three of these cases, the people involved use a variety of methods to communicate and be in dialog with museums about the issues they care about. However, in this post I wanted to highlight how these groups use their physical presence to demonstrate how museums have a real impact on people’s lives and experiences. Since we often of museum objects as being detached from life in their glass cases or boxes, this isn’t always easy to see. But objects are always ready to come to life in conversation with people — put your body to work in a museum today!

Close

Close