The value of ‘offline’ cultural heritage

By Kevin Guyan, on 19 September 2016

By Anna Rudnicka

By Anna Rudnicka

By Anna Rudnicka

Observing a small child approach a museum object and squeak with joy is perhaps the most rewarding part of working in UCL’s museums. I still remember how long it took for medieval kings to put on their Sunday best – just under an hour, apparently, at least in Central Europe – a fact I learnt during a primary school trip to the local castle. Children and adults tend to acquire knowledge more easily when the information is supported by ‘hands-on’ experience of handling or observing an object.

Nowadays, an increasing amount of culture consumption happens online. Will children go to castles in 20 years’ time? Or will they learn history solely from online textbooks and virtual reality tutorials? It has been argued that museums may struggle to compete with virtual reality. The speed with which technology progresses makes it difficult to speculate about the future of the heritage sector. For now, numerous heritage institutions have made an effort to create digital collections. Paintings, sculptures, old books and even historic houses are represented online in digital format – they are often videotaped, photographed or, in case of texts, transcribed. Then, linked by a theme or a story, they become collections. Because of the cost and time commitment required, institutions have been delegating some of these tasks to online volunteers. We are yet to understand how this may affect job prospects, or indeed the security of jobs for those currently employed within the sector.

Digital resources provide us with many new opportunities: we can discover art and historic objects from museums situated thousands of miles away, while sitting at the computer in our comfortable slippers. We benefit from speed of access and lower costs (no plane fare needed) even when conducting extensive online research. Finally, there is the advantage of flexibility. Themes and stories can take precedence over geographic location: objects stored or displayed in remote parts of the world are now only as far as a click or a swipe. We learn contextually.

Although popularity of digital resources could make them seem devoid of drawbacks, the number of British citizens that lack either Internet access or the IT skills required to perform searches in Internet databases, is still high. UCL’s Melissa Terras (Director of UCL Centre for Digital Humanities and Professor of Digital Humanities in the Department of Information Studies) cautions that ‘digital’ does not equal ‘accessible’. It will take time for researchers to achieve a good understanding of what different social and age groups want, and need, form their experience of online heritage.

In the same way that most of us prefer to eat ice cream than to look at it, the experience of material – offline – heritage, can offer us some unique, irreplaceable benefits. Regular library users are more likely to report higher life satisfaction and better overall health. This finding remains valid when many other factors relevant for our wellbeing are controlled for. Learning opportunities afforded by visiting a museum can surpass those inside a classroom. A large study conducted at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art has shown that a trip to the museum resulted in improved ability to think critically about art, and that this effect was particularly pronounced for students from underprivileged backgrounds.

“The experience of material – offline – heritage, can offer us some unique, irreplaceable benefits”

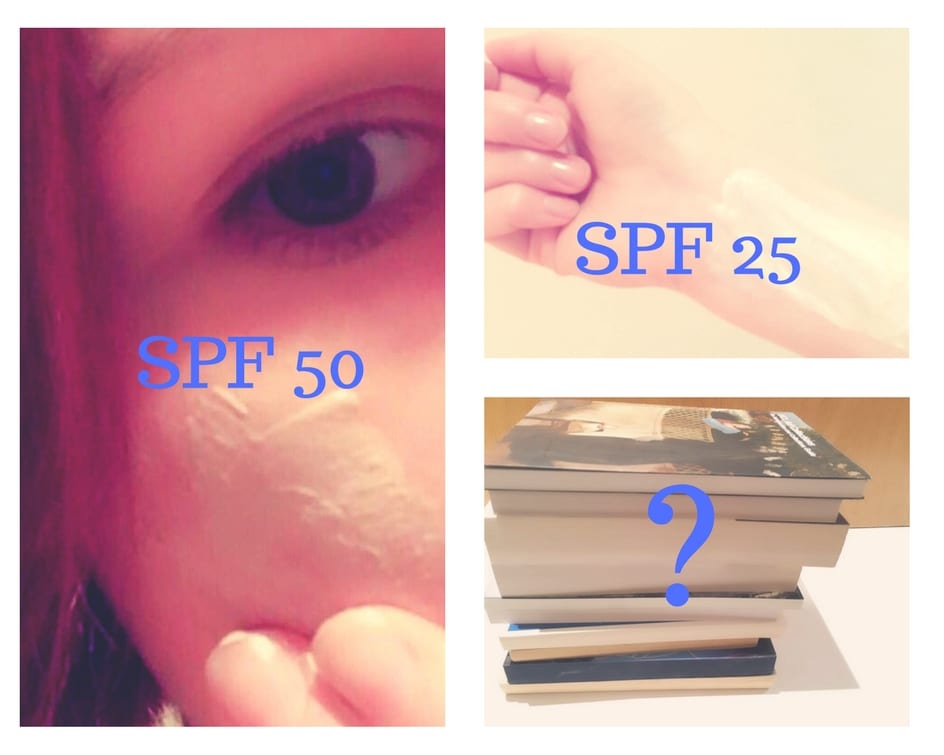

As reminded by Jones and Holden in their seminal pamphlet, we live in a material world. Interestingly, factors such as air pollution, high levels of UV radiation or presence of microbes, are detrimental both to materials that make up our heritage, and to our own health. Perhaps, if we paid more attention to conservation needs of heritage objects, it could result in improved environmental awareness? Since learning about the impact of UV radiation on paintings and other objects prone to fading of colours – I have been a lot more diligent in applying my SPF cream. I am also more interested in pro-environmental initiatives. While heavy Internet consumption may be a sign of the times, it is the material world and material heritage objects that illustrate the consequences of unsustainable behaviours.

Finally, the role of providing access to cultural heritage objects and collections goes beyond personal interests, entertainment, academic study or even the natural environment. By showing us how our ancestors lived, thought and created in the past, heritage institutions teach us the history of humanity. We learn about the things we all have in common, and we are exposed to mistakes that we can learn from. Material objects play a crucial role in educating about the Holocaust. It is their physical real-ness that provides us with an accurate insight into the course of events. Their tangibility and material form offer an experience that is very different from the glamorized version of Holocaust so often depicted by Hollywood or the Holocaust as a generalised concept surrounded by myths and inaccuracies.

Although providing us with new opportunities, online heritage collections are far from perfect: we still need unified description systems, databases that are easier to navigate, and a better understanding of people’s Internet behaviours. Digital heritage and cultural resources allow fast and cost-effective access to information, however, in their current shape and form, we cannot rely on them to provide equal access for all members of the society or to fulfil our duty of honouring the past. It is difficult to foresee the impact that the next few decades may have on the heritage sector, or whether technologies such as virtual reality might bridge the gap between online and offline collections. In the meantime, I encourage you to support your local libraries and museums, especially if they are affected by cuts in funding. You can do this by speaking to your local MP, or by joining an online campaign. The values of material cultural heritage – and the human interaction and learning opportunities afforded by trained staff – should not be taken for granted. My guess is, if we found them gone once we had unglued ourselves from our computers, we would not know how to do without them.

Anna works as a Student Engager and is currently conducting an experiment at UCL’s Octagon Gallery into fading. Anyone visiting the gallery is encouraged to take a photo of the colour chart and tweet it to @HeritageCitSci.

Close

Close