The Grossest (Coolest) Things in the Grant

By uctzcbr, on 23 June 2017

The female Surinam Toad grows her young in small sacks on her back. To impregnate her, her male partner will inseminate her eggs and then lob (not the technical term) those eggs into her back cavities where they hatch. Her young will develop to toadlets before bursting out and going about their life. In the Grant Museum there is a Surinam Toad specimen caught after her toadlets (young toads) have vacated but before she has shed her skin to prepare for the next reproductive cycle. The result is a display of dimples that will make your skin crawl if you have trypophobia – an irrational fear of seeing an irregular pattern of holes in places you wouldn’t expect to see them. I think the Surinam Toad is really gross and, when asked by visitors “what is the most disgusting thing you have here?” this is the specimen I show them. But, whilst they are being weirded out by its back, I explain its back story and truly fascinating reproductive habits because, even though I don’t want to look at the toad, I do want to learn about it.

The underside of a Surinam Toad (W332) with its gross back hidden from view. Click here to see examples of its back sacks, if you dare.

There are a lot of objects in the Grant Museum that are equal parts disgusting and interesting. That is very much to be expected when your collection centres around objects used to study anatomy and collected by Victorian scientists for whom “squeamish” was something that happened to other people. Of course, not everyone thinks that the objects in the Grant Museum are gross, some people do only see scientific objects of historical importance. I am not one of those people, but I still love working in the Grant and sharing its objects with visitors. Even the ones I don’t like looking at, or rather, especially the ones that I don’t like looking at because they are all valuable objects with interesting histories that tell us something incredible about the world. For this blog post, I have chosen my top five (only five!) grossest objects from the Grant Museum so that I can explain why I also think they are remarkable.

- The Surinam Toad, which we have already covered, though I would also like to point out that the male toad embeds the female’s eggs on her back whilst she is doing somersaults so, on top of everything else, this species has pretty good aim.

- The Jar of Assorted Lizards – you may be familiar with the Jar of Moles but, one shelf down, there are some assorted lizards which I think are cooler but they don’t get as much attention because they don’t have as good of a PR guy. There are a lot of jars containing multiple specimens in the museum, which may seem odd because you can’t really get a good look at the things inside them. This technique was used, however, because putting things in jars can be expensive and, having lots of jars requires a lot of storage space. So, if you were storing your specimens, not because you wanted to look at them but, because you wanted to study them you could be a bit more practical and put them all in the same jar. Jars of multiple specimens would have been used to conduct repeat experiments or for class demonstrations or practicals (take one and pass it on). I like these objects because they are a great example of how the Museum collection was originally a teaching collection, even if the thought of ever reaching my hand into a jar is not one I enjoy dwelling on.

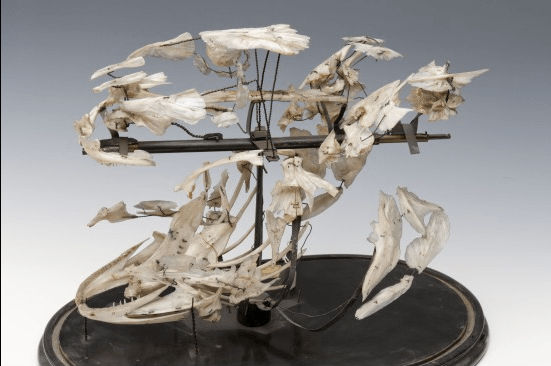

- The Exploded Skulls – when I first started working at the museum, I thought these were art pieces (which is not a bad guess as the Museum often displays pieces of art inspired by the collection). They look very CSI and it is a tad unnerving to see a skull displayed so that it looks as though it has been ripped to pieces. But, these are actually examples of an ingenious technique designed to solve a teaching problem. Let’s say, hypothetically, you wanted to teach your students about horse skulls. You could bring a horse skull to show them but it might be difficult to demonstrate that the skull is comprised of individual bones. Instead, you could bring your students a little pile of horse skull bones and they could examine the individual pieces but they then might struggle to work out which piece was which or imagine the skull as a whole. Beauchene was a technique developed in the 19thC in France where the skull is taken a part and then fixed back together using wires producing what looks like a skull mid way through and explosion. It allows you to see the skull as a whole and as being comprised of separate pieces simultaneously and even to remove single pieces of skull. These skulls look like Halloween ornaments but are also ingenious teaching tools.

An exploded cod skull (V1486). Learn how to make one here.

- The Negus Collection – this collection draws quite a lot of attention and I find it interesting to listen in on visitor conversations as they work out what each of the animal heads are. The specimens in the collection are really good examples of things that you don’t want to look at but can’t tear yourself away from. They contain so much information and allow you to see and incredible amount of detail, but I really can’t get over how meaty they look. Victor Negus, the doctor who prepared these specimens used them to study the throat, in doing so he discovered cures for a number of diseases and also understood, for the first time, the evolution of the larynx and how it enabled us to produce speech. Some people, particularly children, find the display a bit upsetting (there is a bunny rabbit in the collection, after all) as, of all the objects in the Museum, this one does seem to be the clearest reminder that this science was conducted on a lot of dead animals. But, it is also a good example of how important this collection was to science and medicine at the time. I like to explain Negus’s discoveries to visitors because it starts a conversation about how these objects were once used and the scientific learning they facilitated.

- The Flying Squirrel – this specimen, to be quite frank, looks like a tiny, shrivelled alien. Unfortunately, the preserving fluid in this specimen is running very low and serves as a vivid reminder that all of the specimens in the Museum require a lot of care. Currently the Grant is undergoing a long term project, called Project Pickle, to conserve the wet specimens in need of a top up. But, until this specimen’s jar is topped up he is going to look a bit sad and cold to me.

So, those are what I consider to be the grossest objects in the Grant. They are also some of my favourite objects as they each tell us a lot of nature or the historical context of the collection, or how the collection is studied now. There are many other objects in the Grant that are bit unsettling, why don’t you tweet us your favourites with the hashtag #grossestthinginthegrant and we will send you back an interesting fact about them.

Close

Close