The case of the yellow T-Rex

By Mark V Kearney, on 24 January 2019

When I joined the engager team, we were given a great tour of all three UCL museums so as to help us relate our own research to their respective collections. In a simplified nutshell, my work focuses on trying to monitor plastic artworks as they fall apart, by smelling them (more on that in a future blog post). Natural History and Egyptology collections aren’t known for their large plastic collections, so I was naturally a little nervous about how I might relate my work – or at least I was until I spotted the amazing dinosaur collection the Grant Museum has!

My earliest memory of a museum was when I was about 10 and I visited the Natural History Museum in London, for an exhibition which had animated robot dinosaurs. One clear memory I have of that trip was how they looked – the colours and patterns. They all looked like my own toy models, which to a kid is amazing but now as a scientist I find it all little sketchy.

Figure 2 – The museum label for the dino collection — notice the lovely yellow T-Rex in the background! (Author’s own photo)

The models in the Grant are accessioned objects, meaning they are formal museum objects with the same status as some of the most important objects in the collection. They were used to teach students about the form of the animals they were studying. It’s not clear from the label if the colour of the models was also used in their studies. But judging by the bright yellow T-Rex, one would hope not!

But if a T-Rex wasn’t yellow, is there any way that we could know what colour it — or any of the other dinosaurs — might have been? Unfortunately, 65 million years ago they didn’t have quite as active an Instagram as the quokka does.

Amazingly, scientists have found a way to view the colour patterns from fossilized feathers that adorned some dinosaurs. In fact, feathered dinosaurs were more common than initially thought. In a paper published in Science, in 2010, scientists based in China looked at the morphologies (aka the shapes) of melanosomes. These are a small subunit , around 500nm, of a cell which are used for ‘synthesis, storage and transport of melanin’. Using a clever bit of statistics, they learnt that depending on density and length, they could figure out the creature’s colours. Basically, if these melanosomes are long and narrow or short and wide then you ended up with either black and grey colours or with reds and browns respectively.

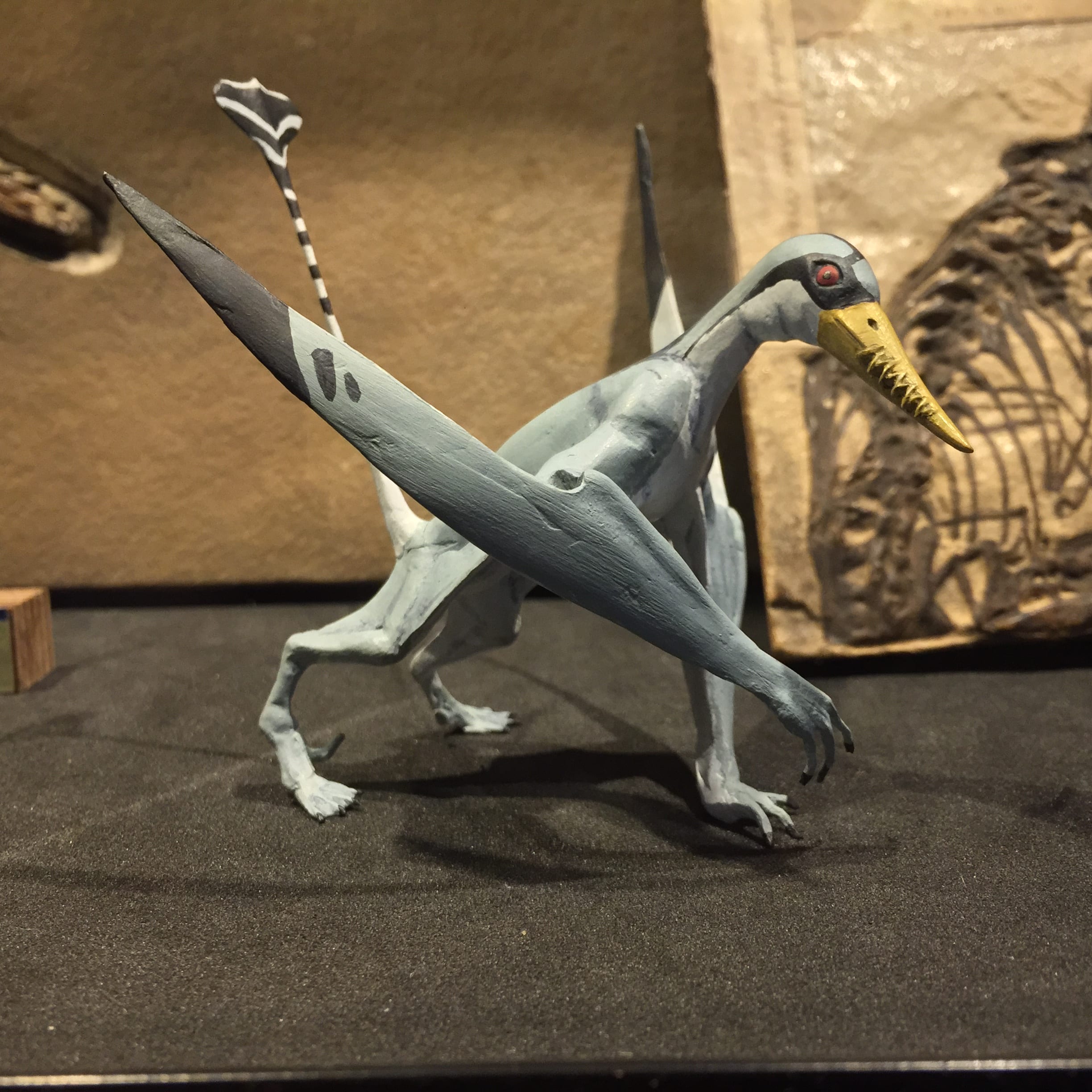

The team in China looked at one dinosaur in particular, Anchiornis huxleyi, which had enough preserved feathers to recreate a full profile of what it would have looked like. What is most striking about their reconstruction is how closely it matches one of the models at the Grant. So while not as totally outrageous as the yellow T-Rex, basing patterns on animals alive now gets you pretty close to what their ancestors may have been like.

Figure 3 – Image of Anchiornis huxleyi showing the resulting colour pattern from the scientific analysis. Photo taken from Quanguo et al (2010)

Figure 4 – A model featured at the Grant, notice its tail whose pattern is similar to that found in the research by Quanguo et al. (2010 )(Author’s own photo)

However, there’s one clear area where the research falls down, and where it’s unlikely that we’ll ever know. Many animals have the ability to camouflage themselves, but given the uncertainty about their habitats millions of years ago (combined with a low number of preserved samples and the fact the only certain types of cells can be preserved), it is very unlikely that we will ever know if dinosaurs were able to blend into their environment.

Let’s end on this thought – through looking at the shape and size of certain parts of cells, and through some fairly understandable stats, scientists are basically able to do some paint-by-numbers on animals that lived over 65 million years ago. Sometimes I am left in utter awe of what science can tell us!

P.S – Plastic Dino figures are not only used in science but also in art – check these out at the new exhibition at the UCL Art Museum.

Close

Close