Question of the Week: How do you Describe the Jaw of a Crocodile?

By Cerys R Jones, on 11 January 2019

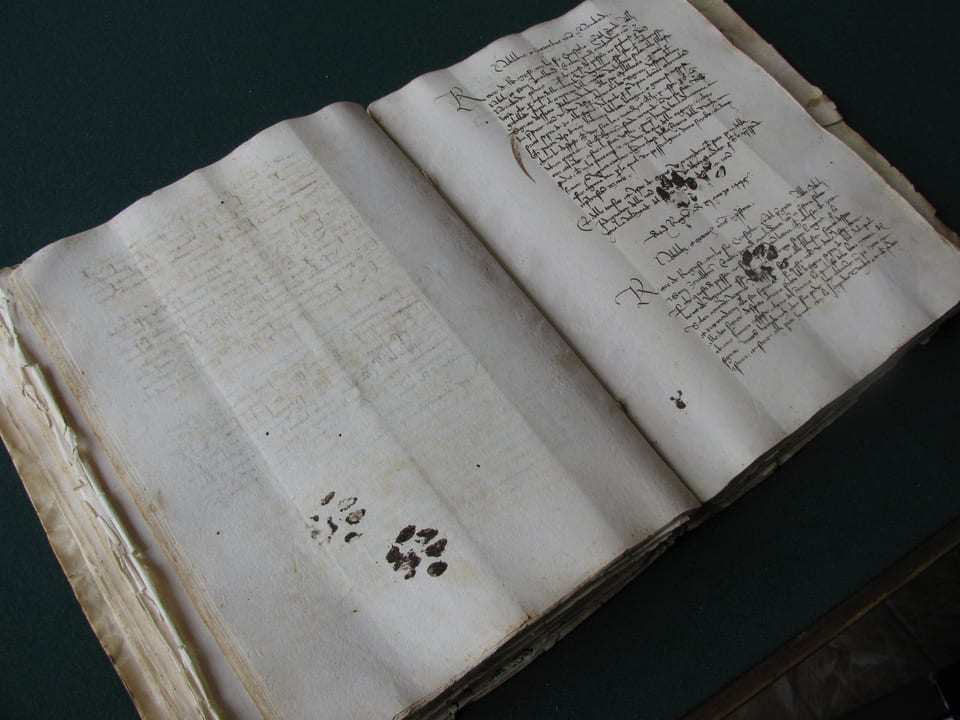

Like many of us, Leonardo da Vinci, the great polymath, wrote “to-do” lists. However, in true Leonardo form, his lists did not contain typical mundane tasks such as ‘pick up milk’ or ‘post mum’s birthday card’ but instead provide a fascinating insight into the mind of the Renaissance great. The entries on Leonardo’s list include ‘obtain a skull’, ‘describe the tongue of the woodpecker’ and ‘describe the jaw of a crocodile’. In the spirit of the New Year, with the motivation of completing tasks and resolutions, this blog post aims to tick off one of Leonardo’s 500-year-old objectives.

To start with, let’s return to a previous blog post by UCL museums that discussed the differences between crocodiles and alligators. It includes the location (alligators are typically found in North and South America, whereas crocodiles are typically found everywhere else), how porous the skin is (alligators only have pores around their jaws, whereas crocodiles have them everywhere), and also the shape of the jaw. The blog post states that the crocodile’s jaw is narrower than the alligators: it is more of a V shape whereas the alligator’s is more rounded at the end, like a U. The jaw is also straighter in an alligator than a crocodile and crocodiles have bottom teeth that extrude from the bottom lip. This is enough information if you are simply looking to identify your crocodiles from your alligators but, for curiosity’s sake, we will continue.

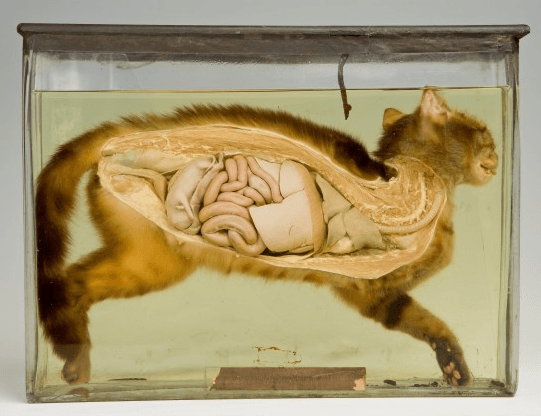

Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo mentions the inventor’s interest in crocodile jaws. Isaacson states that “a crocodile, unlike any mammal, has a second jaw joint, which spreads out the force when it snaps shut its mouth. That gives the crocodile the most forceful bite of any animal. It can exert 3,700 pounds per square inch of force, which is more than thirty times that of a human bite” [1]. According to Science Daily, crocodiles have likely retained this ability since the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs roamed the earth].

A rather humorous experiment involving “ten gigantic crocodiles” was described in an article in Scientific American published February 25th 1882. The aim of the experiment was to calculate the strength of the muscles of the crocodile’s jaw, which they determined as 1540 lb, although noted that “this experiment was performed on a crocodile already weakened by cold and fatigue, its force when in its natural conditions of life must be enormous”. The text also mentions “how difficult it must be to manage such ferocious animals in a laboratory” and measures some of the crocodiles as ten feet long and 154 lb in weight! Leonardo was possibly interested in these creatures for their warfare potential. After all, he was hired as a military engineer and creatively designed weapons and armour.

Sketch of the experiment to determine the power of a crocodile’s jaw in Scientific American (Copyright: Universal History Archives, via Scientific American)

Although Leonardo has a bit of a reputation for not finishing his works (look at the Adoration of the Magi, the Battle of Anghiari, and Saint Jerome in the Wilderness to name a few), Leonardo did in fact complete this task. He wrote in one of his notebooks “[the crocodile] is found in the Nile, it has four feet and lives on land and in water. No other terrestrial creature but this is found to have no tongue, and it only bites by moving its upper jaw”. This actually isn’t entirely true. The crocodile does have a tongue – in fact, the female crocodile uses her tongue to help crack the eggshells of her young. There are also many scientific papers that discuss the tongue of a crocodile (for example, see [2]). Furthermore, ‘The British Cyclopaedia of Natural History’ published in 1837 mentions that the crocodile only moving its upper jaw was an “old belief” [3].

Leonardo’s inquisitive mind and thirst for knowledge is reflected on every page of his notebooks. He fills them almost entirely with his fervent list-keeping, avid note-taking, and intricate sketches. The child-like fascination with every aspect of the natural world is a quality that enabled him to become an expert in many areas of studies, including art, anatomy, optics, and geology.

As we enter the New Year, a time for reflections and new beginnings, we could all do with “being more Leonardo” and seeking the answers to life’s curiosities. What unconventional item will you add to your next “to-do” list?

References:

[1] Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci: The Biography (Simon & Schuster, 2017), 398.

[2] J.F. Putterill and J.T .Soley, “General morphology of the oral cavity of the Nile crocodile, Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti, 1768). II. The tongue,”The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research71.4 (2004): 263-77.

[3] Charles Frederick Partington, The British Cyclopaedia of Natural History (Orr & Smith, 1835), 550.

Close

Close