The practice of consanguineous marriages in our modern societies

By Alexandra Bridarolli, on 8 February 2019

This is the fourth and final segment in a series on incest; you can go back and read the previous segments on incest in ancient Egypt, incest in the Hapsburg family, and incest in nature.

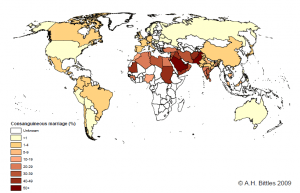

As surprising as it may seem, consanguineous marriages are nowadays respected and practised among more than one billion of the world’s population, in particular in the Muslim countries of North Africa, Central and West Asia, and in most parts of South Asia (Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi 2008) with consanguinity rates reaching 20–50% (Hamamy 2016). It has been shown (Bittles 1994, 2001) that sociocultural factors, such as the maintenance of family structure and property, ease of marital arrangements, better relationships with in-laws, and financial advantages relating to dowry, seem to be strong contributory factors in the preference for consanguineous unions.

In countries with civil unrest, consanguineous marriages are preferred because close-kin marriage is regarded as safeguarding for personal and family. It has also been suggested that marriage dissolution and divorce is lower among cousin couples. Studies have indicated that women in first-cousin marriages are protected against intimate partner violence. In another study focussing on cases of consanguinity in Iran (Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi 2008), the authors also demonstrate that in this country the ethnicity, province and area of residence have remained by far the most important determinants of the practice of marriage to biological relatives. In contrast, the modernization variable, education, had no significant effect upon behaviour, the effect being only for those with tertiary education.

Figure 1: Global prevalence of consanguinity (Bittles 2009)

In other countries, the genetic risk associated to consanguineous relations is taken very seriously and all is done to avoid it. This is the case with Iceland. With a population of only 320.00 inhabitants, the risk of incest is really high. De facto, in Iceland everyone shares at least one family relationship. It is said that one of the most asked questions during a first date is: “Hverra manna ert þú?” Which means “ Who are you, who is your family?” To avoid any chance to end up dating your cousin, 3 engineers have recently created a smartphone app called ÍslendigaApp in which people can check the family genealogy and any family relationship with their intended in a few seconds. It even has a “bump” option which gives the info on family relationships when the partners’ phones are clashed and can even send an “incest alert” when the two partners are close family members.

At the origin of this app, there is a genealogy website called Íslendingabók (i.e. Book of Icelanders). Launched in 2010, the database lists the family relationships between Icelanders going back 1200 years. To check the information related to your family, any inhabitant of the Island only needs to provide his/her name and national identity number. Quickly, the website starts to be much more than just a catalogue of genealogy trees and people started to use it to check any possible family connections to their partner.

Here the series on Incest ends. Through the different articles of this series, I have tried to elucidate the incest taboo, find its sources, and understand its origins through different historical cases — Tutankhamun or the Habsburg family — but also through scientific cases. All these examples have shown us that this taboo seems deeply anchored in nature and culture but that neither nature nor some cultures totally prohibited it. So where to find its source? The questioning hits some dead-end; the answers provided are always partial. Psychology has tried to stick its nose into it while some scientists are waiting for the discovery of a possible “incest” gene. While we wait for answers, I would like to ask you: “Why do you find incest disgusting?” I hope these articles gave you some food for thoughts and starting points for further questioning.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” (Hamlet by W. Shakespeare).

References

Bittles A. H. (1994). ‘The role and significance of consanguinity as a demographic variable.’ Population and Development Review 20(3):561-583.

Bittles A. H. (2001). “A Background summary of consanguineous marriage.” Center for Human Genetics, Edith Cowan University, Perth.

Bittles, A. H. and M. L. Black. “Consanguinity, Human Evolution, and Complex Diseases.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107.Suppl 1 (2010): 1779-86. Web.

Hamamy, Hanan, and Alwan, Sura. “Chapter 18 – The Sociodemographic and Economic Correlates of Consanguineous Marriages in Highly Consanguineous Populations.” Genomics and Society, 2016, pp. 335–361.

Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad, et al. (2008). “modernization or cultural maintenance: the practice of consanguineous marriage in Iran.” Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(6):911–933.

One Response to “The practice of consanguineous marriages in our modern societies”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] in Glass (Anna Pokorska), 7 reasons Bes should be your favourite Egyptian god (Cerys Jones), The practice of consanguineous marriages in our modern societies (Alexandra Bridarolli) and When Plastics Saved Turtles (Mark […]