The leg bones connected to the hip bone…

By Mark V Kearney, on 28 November 2018

One of the nice benefits of working as a student engager is that during the down times when there aren’t that many people in the museum — the last 20-30 min before closing gets pretty calm — I have a little time to explore the collection. Despite my lack of formal study in biology (a strange feature of the Irish school system which allows one to obtain a degree in science without having to study biology), I have always really enjoyed my explorations in the Grant Museum of Zoology.

I’ve spent the majority of my time as an engager working at the Grant rather than the other museums and I keep coming back to the same observation when I look into the display cases: Why would animals evolve to have fibulas that seem so incredibly fragile? It’s a weird observation I know, but I’m a Physicist at heart and these mechanical aspects jump out at me.

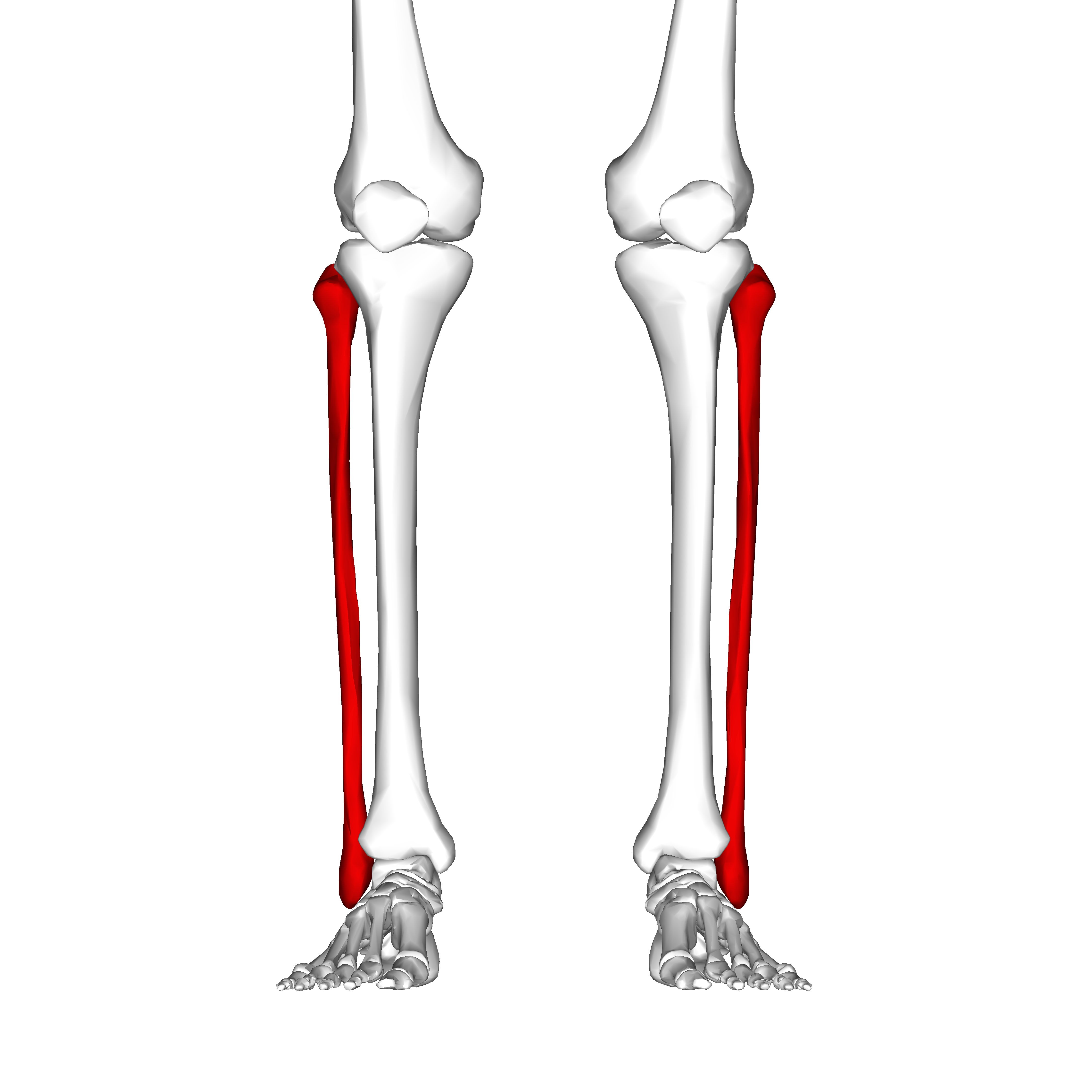

The fibula is a very slender bone that is found in the lower leg and sits behind the tibia.

Now the issue I have with the fibula is this: our leg bones need to be strong enough to run on, how else would we evade some other animal that’s trying to eat us… and that goes for most other animals too (FIG.1). But why then is it so slender? What is it actually doing? Why don’t we break it all the time? And if it’s more of a hindrance to use, why haven’t we evolved to remove it?

Let’s start by talking about what it does – from the reading I found for this blog it would seem that it doesn’t do very much. The fibula only takes about 10% of body weight and that is likely the answer to why it’s so slender. It doesn’t need to take as much weight as you might think; the tibia does that and that bone is multiple times the fibula’s diameter. The fibula also connects some muscles together and in the case of humans, it helps keep our ankle stable when we move.

More tiny fibula, this time from a Macaque on display at the Grant (Author’s own photo)

This Tree Shrew on display has a broken fibula… kinda proving my point that they break easily… (Author’s own photo)

Trying to find out about how often we fracture the fibula has proven more difficult than I thought. The studies that I have found don’t separate it from the tibia or sometimes they lump it in with the ankle making it hard for me to judge if it’s the tibia or the fibula that break first – though I did find one study suggesting the ‘fibula made up 12% of the tibia/fibula fracture cohort’. But that was only one reference so we won’t base everything off of that! At about 10% of fractures, that area seems to be one of the more common ones to get broken.

If the fibula doesn’t do much or if other things could do it better why do animals still have it and why hasn’t it been removed over the years via evolution? Well, it turns out that some animals are doing just that! First off, humans still have it because all tetrapods have inherited this basic form; we all ‘share the same pattern of bones in [our] limbs’. But some animals have started to evolve to do without it. For example, scientists have studied chickens and by looking their ancestors, early theropod dinosaurs, they’ve found that the fibula is now shorter and ‘splinter‐like toward its distal end’. This idea of the reduction of the fibula isn’t new at all… in fact, one reference I found is dated to 1918!

Through noticing the peculiarities of fragile fibulas my research has led me to learn more about the function and form of the skeleton, evolution, and finally landing on dinosaurs (which is always a great place to end up after a days research!) . That’s the beauty of museums, you can go in to kill some time and end up learning something fantastic!

Close

Close