What if Bob Dylan became Pharaoh of Egypt?

By Sarah M Gibbs, on 28 June 2018

“For the times they are a’ changin’ ”

-Bob Dylan

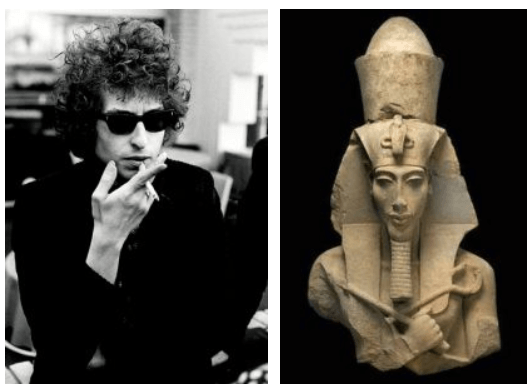

Bob Dylan in Don’t Look Back (http://nostalgiacentral.com); bust of Akhenaten (http://www.crystalinks.com/akhenaten.html)

If I were to invent a new board game, I’d call it “Who are you now?” Players would have to imagine who historical figures would be if they were alive today. Alexander the Great? A corporate raider leading hostile takeovers and selling dismantled companies to the highest bidder. Christopher Columbus? The captain of the first mission to Mars. Jean Jacques Rousseau? Head of a yoga ashram and wellness retreat in the Cotswolds. And Akhenaten, the iconoclastic pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, artefacts from whose reign are on display at UCL’s Petrie Museum, would definitely be Bob Dylan.

At first glance, the son of Amenhotep III and the folk singer from Hibbing, Minnesota may not seem like brothers from other mothers. Fair enough. The two men’s lives are separated by nearly three thousand years, and many more thousand miles. But the careers of king and artist, both of whom defined the cultures of their respective periods, evince intriguing similarities.

Let’s consider some points of convergence, shall we?

1. Artistic Revolution

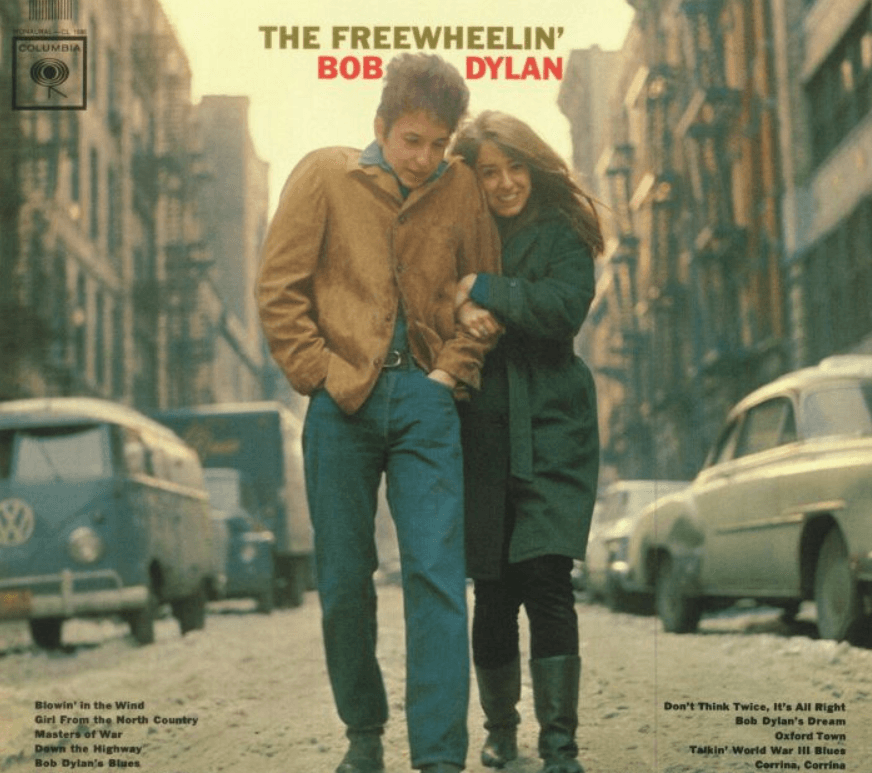

Bob Dylan’s breakthrough album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was released in 1963 (bobdylan.com) and launched a folk revival which defined popular music for the remainder of the decade. After the dominance of Frank Sinatra-style crooners in the 1950s, Dylan’s productions—featuring simple arrangements and complex, poetic lyrics sung by a vocalist of limited range—were a complete departure from the musical mainstream.

Akhenaten likewise upset the artistic establishment. Have you ever tried to “walk like an Egyptian”? Traditional Egyptian reliefs employed multiple viewpoint perspective, a technique which presented the parts of the human body in the positions in which they appeared most attractive: head and legs in profile (feet staggered) while chest and torso faced the viewer . In contrast, the relief images produced during Akhenaten’s reign featured naturalistic representations of the body; positions and postures were relaxed, and round hips and bulging bellies were on full display.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Meritaten Worshipping the Sun-God, Aten (Petrie Museum UC401; alabaster relief)

2. Religious Upheaval

The perception of Dylan in the 1960s as a truth-telling artist of the people led his most devoted followers to view him as a prophet (one more-than-slightly deranged fan picked through his garbage in New York City looking for said “truth”). Surreal, dystopian songs like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” added to the effect.

Akhenaten actually did change Egypt’s religion. He was king. He could do that. Ushering in one of the first eras of monotheism in the ancient world, the Pharaoh replaced Egypt’s pantheon of gods with worship of the sun-god in his celestial “disk” form.

3. Name Changin’

A revolutionary needs an epic name. Robert Allen Zimmerman, son of a furniture store owner in small-town Minnesota, became Bob Dylan. And Amenhotep IV was reborn as Akhenaten; he incorporated the Egyptian word for “disk” (“Aten”) into his new moniker to honour his one-and-only god.

4. The City Founders

Following a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1966, Dylan retreated from public life. He went to Woodstock in upstate New York, and other artists followed, most notably The Band, whose debut album, Music from Big Pink, was written in Woodstock and features the classic song “The Weight.” George Harrison of The Beatles also found his way to Dylan’s idyll.

Admittedly, Akhenaten went a little bit bigger. In the sixth year of his reign, the King founded a new city in middle Egypt between the government and spiritual hubs of Memphis and Thebes. He called the city Akhet-Aten (today it is known as Tell el Amarna) and dedicated it to his god. The Collection at UCL’s Petrie Museum includes a number of reliefs and pottery fragments from the city.

While Dylan continues to endure, and to frustrate groups like the Nobel Prize Committee (he failed to show up to collect his honour), Akhenaten ruled for only seventeen years. After his death, Tell el Amarna was abandoned, and Egypt reverted to polytheism. The commune broke up. The flower children had to get office jobs. Some revolutions just don’t last.

“It’s all over now, Baby Blue.”

-Bob Dylan

Close

Close